As a project grounded in making, Conference Creatures resonates with scholarship on craft as rhetoric. We draw particularly from Leigh Gruwell (2022), who understands craft as "material, process-oriented practices of making that foreground the intra-actions between humans, objects, and their environments" (pp. 31–32). Importantly, Gruwell continued, "these intra-actions—as material manifestations of power—are always political, and thus, craft understands relationships as the condition for rhetorical practice" (p. 32). Approached through this framework, the act of crocheting and knitting creatures becomes more than a hook or needle weaving yarn (although Conference Creatures is that, too). Because "craft always regards the material as mutable" (Gruwell, 2022, p. 14), Conference Creatures as craft productively entangles people, creatures, and values to push for feminist professional praxis.

Indeed, a recent body of research has surfaced the rhetorical power of craft. Heather Pristash, Inez Schnaechterle, and Sue Carter Wood (2009) identified needlework as a form of epideictic rhetoric, which forwards cultural values, encourages audiences to "imagine possibilities that need to be enacted in the world," and inspires action (p. 15). Crucially, these qualities emerge through both the final craft produced—including, say, a crocheted creature—and the process of crafting that object. Similar to Kaela Jubas and Jackie Seidel's (2016) reflections on their knitting circles as sites where they co-produced new knowledge and affective orientations toward the neoliberal academy, we find that the process of crocheting creatures generates new ideas and relationships.

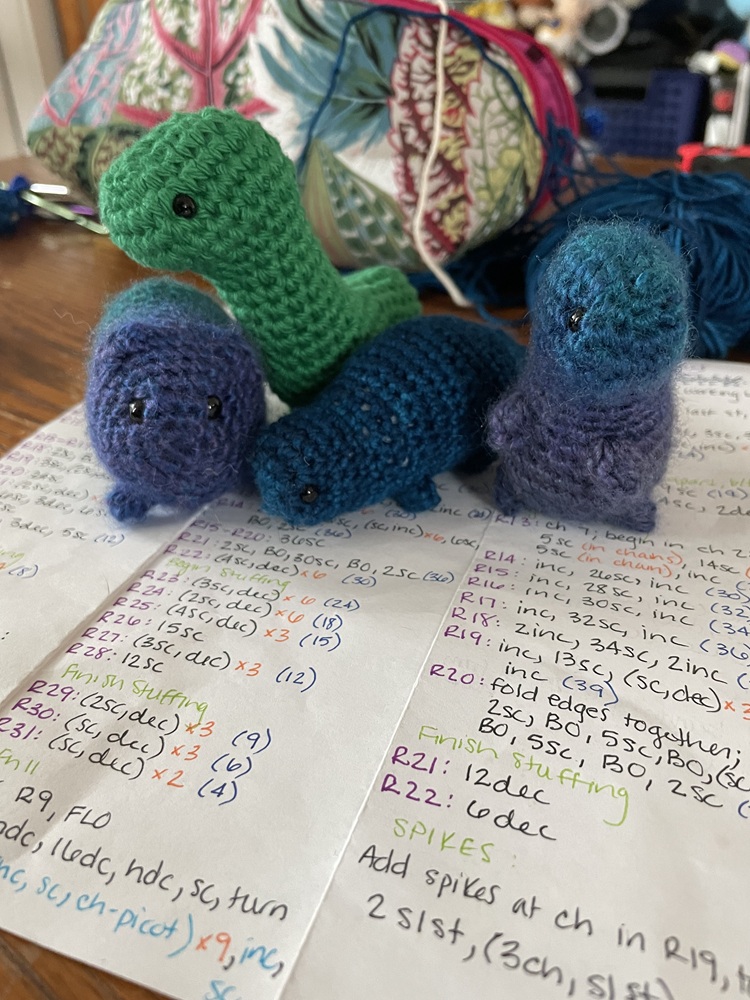

Maureen Daly Goggin and Shirley K. Rose (2021) further explicated crafting as a material, embodied rhetorical practice of knowledge-making. For Goggin and Rose, "material practices, those the hands perform, are a form of knowing that (episteme), knowing how (techne), and wisdom making (phronesis)" (p. 4). In the case of crocheting, making requires reading patterns, decoding common stitch abbreviations, knowing how to form (and "frog," or undo) different stitches, and feeling out the right amount of tension for a project. With enough experience and creativity, crocheters also adapt existing patterns and invent new ones to suit their needs. As rhetoric, craft is situational and epistemological.

In addition to being both situation- and knowledge-based rhetoric, craft is methodological. Amanda R. Tachine and Z. Nicolazzo's (2022) description of weaving as "a long-standing practice of cultural survivance" (p. ix) recognized the power of craft to persist and resist colonizing powers. Building from Tachine and Nicolazzo's craft as survivance, Angie Morrill and Leilani Sabzalian (2022) offered their Indigenous survivance storytelling methodology. By offering examples of survivance work through storytelling, Morrill and Sabzallian illustrated how their "practices of recognition, of space-making, of crafty self-determination" (p. 39) facilitate decolonial inquiry and resistance through community relationalities. Understanding craft as survivance and survivance as methodology situates craft, in this context, as methodology.

Not only is craft inherently rhetorical, but rhetoric, as Gruwell (2022) put it, is "inherently crafty" (p. 7). As Gruwell explained, "craft helps rhetoric articulate the ethical implications and political consequences of the intra-actions that make it possible" (p. 41). The craftiness of rhetoric asks us to foreground rhetoric's political nature and its ability to make change through material collectives.

Toward this end, Conference Creatures intentionally tugs on threads of craft's anticapitalist history. Both Goggin (2009) and Gruwell (2022) highlighted craft's place in the art/craft binary. While "art" tends to refer to laudable public creations coded as masculine, "craft" calls to mind supposedly unserious hobbies that are gendered as feminine. This harmful, patriarchal binary has not gone unchallenged, though. Gruwell (2022) recounted how the nineteenth-century Arts and Crafts movement, spurred by a Marxist resistance to capitalist industrialization, worked to "undo the strict binary that separated art from craft," recognizing how this differentiation "is gendered as well as classed" (p. 42–43). This movement further aimed to cement craft—both making and taking pleasure in crafts—as a right to which women and working-class people should have access. At its core, the Arts and Crafts movement "celebrated the individual laboring to produce honest, unique, and functional goods" (p. 42) against a backdrop of industrial alienation and commodification.

By pursuing craft outside of the capitalist economy, Conference Creatures rejects market logics. Although we have received repeated suggestions to sell creatures, we stand firm in our belief in the value of gifting and reciprocity instead. Creating without the end goal of producing a commodity to be sold allows us to crochet free from worries about mistakes and the pressure of perfection. At the same time, we bring creatures into academic spaces and insist on the intellectual value of this praxis to push back on entrenched neoliberal ideologies. Following Jubas and Seidel (2016), we argue that each stitch that builds up Conference Creatures constitutes an "opening" or an invitation to reconsider and rework norms of productivity, efficiency, and labor. While we are gaining some amount of academic capital through theorizing Conference Creatures in the form of a scholarly publication, we do so out of necessity as graduate students, and out of a desire to transform our field from within.

Furthermore, while rejecting capitalist market logics, Conference Creatures as a project also aims to minimize colonial research logics. While Conference Creatures does not attempt to function at the level of Morrill and Sabzallian's (2022) Indigenous survivance, their methodology allows researchers to disrupt institutional and cultural hierarchies while creating practices of recognition within academic spaces. By stitching relationalities and crafts to our methods of inquiry and project design, Conference Creatures refuses traditional academic hierarchies within professional spaces and expands them. Inspired by the examples of Tachine and Nicolazzo (2022), along with Morrill and Sabzallian (2022), Conference Creatures might be understood as a small example of decolonial praxis.