"Sonic Medicine" and Scott Kolbo's Book of the Grotesque

This is Not Scott Kolbo

"My work springs out of the tradition of satire, which I became interested in as a young man after looking through many, many art books in the library and realizing that I was most attracted to prints with funny looking people in them.... I create drawings, prints, installations, and projections where fragments of reality mix with exaggerated environments and grotesque characters."

- Scott Kolbo (2009) in Ruminate Magazine

"I have always loved the idea of using visual art to create narratives. Much like a writer or filmmaker I have built up a pantheon of reoccurring characters and environments that allow me to investigate some of the social, political, and ethical issues that confront private individuals and communities in contemporary society. I prefer to fragment my stories rather than rely on a traditional narrative structure—so most of the pieces I produce are vignettes and brief glimpses of a larger slapstick comedy world."

- From Scott Kolbo's (2013a) Artist's Statement

Is "Sonic Medicine" a Comic?

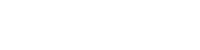

In "Perspicuous Objects," I write about Scott McCloud's (1993/1994) idea that comics are “juxtaposed pictorial and other images in deliberate sequence” (pp. 6–9) and about Joseph Witek's (2009) audience-focused idea that to be read as a comic is to be a comic. I also suggest that, if nothing else, comics become recognizable as comics with the presence of two things: cartoons and a concatenation of visual signs. By any of those standards, Scott's broadside may be read as a comic, complete with cartoons, a concatenation of visual signs, comic book-style panels, and images that are deliberately sequenced and arranged. Of course, Scott's work might be interpreted in light of its relationship to other artistic traditions, and "Sonic Medicine" is not the kind of comic most readers imagine when they think of comic books. But the broadside signals its affinity with comics and invites reading as a comic. In what follows, I attempt that sort of reading after taking a relevant detour through Scott's investment in satire and the grotesque.

Kolbo Grotesque

Scott has a longtime interest in visual satire, human figures distorted in telling ways, and the sorts of grotesque characters that appear in work by writers like William Faulkner and Flannery O'Connor. Those writers themselves were inspired in part by the work of Sherwood Anderson (1919/1992). In "The Book of the Grotesque," Anderson portrayed an elderly writer who wrote that to be grotesque is to be fixated on just one truth:

It was the truths that made the people grotesques. The old man had quite an elaborate theory concerning the matter. It was his notion that the moment one of the people took one of the truths to himself, called it his truth, and tried to live his life by it, he became a grotesque and the truth he embraced became a falsehood. (p. 6)

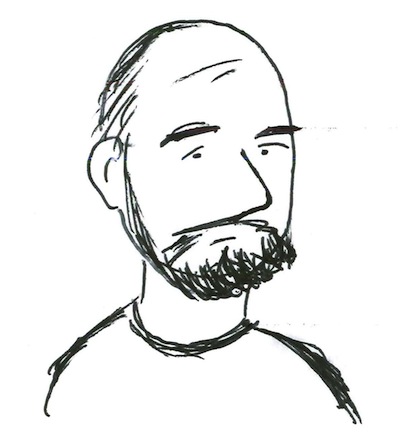

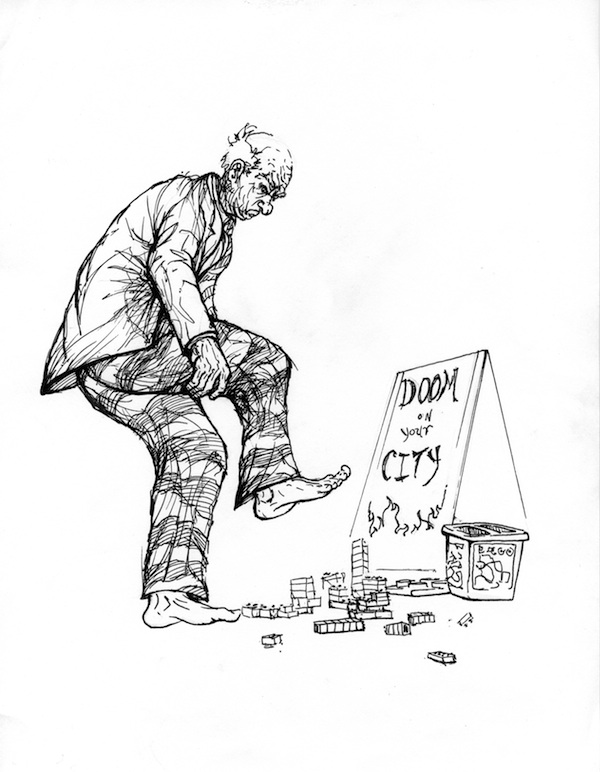

I don't want to say that Anderson's presentation of the grotesque accounts for everything in Scott's figures, but it sheds some useful light. Jeremiah, the street preacher, is fixated on the notion of himself as a man sent to save the world by attacking its imperfections with shouted sermons. In the ways Heavy Man responds to his life, he seems to have attached himself to a set of truths nearly opposite to Jeremiah's, so that an ugly world inspires in him not action or words but a paralyzing sense of inefficacy. Several things are happening with the Alley Kids in "Sonic Medicine," and being young somehow makes them seem less set in their ways or worn into grotesque points of view than Jeremiah and Heavy Man. But Scott shows through their actions and positions the kinds of truths they're beginning to embrace.

The cursing girl—the Princess—is a manifestation of Jeremiah's nemesis, a source here of corruption, dominating and filling up her world with coarse, badgering language, much as Jeremiah would like to fill and reshape the world with his shouted correctives (but never can). In "Sonic Medicine," the medicinal magic of the Princess's words is far more powerful than are Jeremiah's words, which warrant no visual representation. The Princess's use of language makes her the center of all things for these characters and in this moment. The three Alley Kids nearest the Princess, in their languorous, detached poses, and even in the way they are clustered around the Princess, suggest their passive acceptance of her coarseness. Her way of dominating the world is normal and unexceptional for them. The two children positioned away from the Princess are having different adverse reactions to her. The first has a Heavy Man-like avoidance: head down, detaching, blocking out the Princess's words, which seem directed at him. The second, mouth wide open, hands on her ears, is being literally blown aside by the language of the Princess. Is this girl screaming to cover the sound of the Princess? Or is this just a mouth wide open in shock? It doesn't matter, exactly. What's clear is that she, like Jeremiah, resists, and that she, like Jeremiah, is pushed back. Her words or sounds, like his, fail to fill and shape space as the Princess's words do.

One way of understanding what Scott presents here, then, is to see this as a group of people locked into different, grotesquely narrow ways of acting in, shaping, and responding to their shared environment, which itself is an imperfect, cramped, broken-down space that makes conflict all but unavoidable. There is no sage savior character here who arrives and knows just how to act or how to bring about reconciliation. There are only actions and responses, none wise, all limited by the narrow ways these characters understand their world and act in it. (And then there are those birds, which I explore below.) It's important to notice that the meanings suggested here arise not from the form of any one of these figures or from the line style alone but from the concatenation of all those things (and more).

Kolbo Comic

Chris Ware (2001) has made the vivid suggestion that we should respond to cartoons in the same way we would respond to the sight of a man drowning—instantly, without considering the grace and subtlety of his gestures. In that formulation, Ware (2001) argued for a view of cartooning as producing an efficient symbolic language, not as organized and predictable as an alphabet, but instantly readable. That fast reading is made possible by what Scott McCloud (1993/1994) has called "amplification through simplification" (p. 30), the abstraction process that strips away subtleties to emphasize certain attributes of a depicted person or object. McCloud's (1993/1994) "amplification through simplification" is much like the sign-making process described by Gunther Kress and Theo van Leeuwen (2006): in depicting (and thus abstracting) a person or object, the signmaker emphasizes its "criterial aspects" (p. 6); beyond that, the signmaker includes "possessive attributes" necessary to their purposes (p. 98). In this account of how comics work, the readability of cartoons is rooted in the way that a cartoonist selects and emphasizes salient details, leaving out distracting details and quickly—instantly, if all goes well—focusing readers on the relevant attributes of the characters and situations depicted.

So is "Sonic Medicine" as instantly readable as a drowning man's arms? In one way, the answer is no. No one will get to the bottom of "Sonic Medicine" in a single fast reading. However, one can begin to see what's happening in "Sonic Medicine" with an initial reading, and that's what counts here. A quick reading won't explain those birds, but it will give a pretty good sense of the place, the characters, and the story. In short: With crass, violent language, the Princess is verbally assaulting another Alley Kid (or maybe two other Kids) while still more children sit by, almost wholly passive. The Princess's voice fills the neighborhood like foul smoke, invading everywhere. Heavy Man feels burdened but does nothing about the Princess. Instead, he walks inside a nearby building, stops in his tracks, and falls through the floor. At the same time, Jeremiah hears the Princess and attempts to answer her with his own harangue. He is met with physical violence in return, thrown stones coming from the direction of the Alley Kids. Then birds arrive, and they finish the job begun by the Kids and their stones, knocking Jeremiah down, incapacitating him, and thus stopping his voice. Meanwhile, some of the birds raise Heavy Man out of the basement, back toward the Alley Kids. He seems strangely resigned to what the birds are doing. That much is almost immediately clear.

Also clear is that this is a poor, unhappy neighborhood in bad repair. The concatenation of signs instantly shows that to be the case: broken and uneven fence slats, an untended fence-line, piled-up junk with grass growing around it, a home in disrepair, and a patched-up garage. The chair outside Heavy Man's home is an indoor chair used and left outside, and through his narrow door we can see bureau drawers that are not quite closed. Nothing is new, nothing is tidy and organized, and nothing shows the mark of any recent effort to make this place nice or beautiful. Heavy Man's fall extends the mess, as does the attack of the Alley Kids on Jeremiah. Kress and van Leeuwen (2006) described how a child drawing a car might choose circles as the wheel-like criterial aspect necessary to represent car-ness (p. 6). Naturally, Scott did not choose and represent just one aspect of the figures and scenes he drew, but it is clear that the concatenated set of attributes he provided here had to convey, for his purposes, that this is a run-down, untended place that forces otherwise unrelated people of all ages to live uncomfortably close to one another, regardless of personal preferences or affinities.

As with the narrative's setting itself, the general character of Heavy Man can quickly be read using the visual signs Scott provides. Heavy Man wears rumpled clothes to match his rundown neighborhood, and moves uncomfortably toward his shabby little home. That physical discomfort, along with his unkempt appearance and droop-shouldered posture, immediately signals something about Heavy Man's way of being in the world. His downcast head and worried expression carry that same message about his burdened passivity. Heavy Man’s passivity is explicit and unchanged throughout the broadside, even in the moment where he freezes inside his house, responding to the Alley Kids by becoming unable to move at all, so heavy (magically and metaphorically, now) that he is about to fall through the floor. It is not only clear that this is Heavy Man's space, a place where he lives or stays, but also that this place is being saturated with the words of the Princess and that Heavy Man doesn't like what the Princess is doing. The Princess's words are visualized on the page in part as conventional cartoon cursing (%$#@!) and in part as the stars that conventionally appear around a cartoon who has been struck violently. Some of the biggest stars are near Heavy Man's head in his first frame. His passivity, burden, and pain in the face of actions that disturb him are clearly, quickly, wordlessly communicated. Again, criterial aspects of the figure are conveyed through a concatenated set of visual markers.

We don't know Heavy Man is sad and passive because Scott has somehow chosen heavy and depressed lines for Heavy Man. The same general kind of linework, after all, makes Jeremiah disgruntled and aggressive. It is fair to say that the linework matters and that the level of detail contributes to the making of Heavy Man, but the linework doesn't work alone. Heavy Man is also characterized by his posture and positioning, his surroundings, the pointedly-included presence of the Princess and the other Kids, the contrast to Jeremiah, and the sequence of actions. Everything on the page around Heavy Man signals or exacerbates his sad, rundown heaviness, and (going a little further than a first reading might go) the heaviness appears to be a kind of magical manifestation of or result of his passivity and his grotesquely low sense of self-efficacy. It would be possible to do an even more granular reading of this text, teasing out significances from the tiniest of details, and in some cases it might even be desirable to do so. Here, though, my goal is only to show how a general sense of what Heavy Man is all about, like the sense of what this place is like, results from a concatenated set of visual signs appearing throughout the broadside. Those signs together, not alone, help Scott evoke more or less what he wants to evoke. Heavy Man's full significance emerges only from the whole of "Sonic Medicine."

Kolbo Concatenated

Cartooning can be regarded as fundamentally grotesque. Cartoonists are always drawing focus to particular outsized traits and foibles of characters and spaces. That this is at least true of Scott's work becomes more clear as a reading of "Sonic Medicine" proceeds and begins to account for contrasts between his characters, who respond in their own obsessive ways to the scene. Of course, those contrasts are a result of what might be thought of as another level of concatenation, where we are not simply asking who Heavy Man is or who Jeremiah is, but are asking what Scott gets at by placing them into this situation together, up against the Princess.

To begin with, Jeremiah's response to the Princess is visually contrasted with Heavy Man's. At the top, in the broadside's first tier, the two men occupy opposite sides of the page, in panels of similar size. Positioning, along with the Princess's invading cloud of language, implies that they both are responding to the Princess. Jeremiah and Heavy Man share a general scruffiness (even in their lines). They are also alike in their isolation from any other human being; they act (or fail to act) alone. Beyond those details, the two men are substantially different from one another. Jeremiah is only passing through this place, not anchored to it as Heavy Man is anchored to it, and the old man is free to ignore the Alley Kids and move on. Jeremiah is connected to some kind of conventionality with his suit and tie, but he is also unkempt and rumpled, barefoot in a dirty alley full of debris. Whatever conventionality he aspires to, it is not a conventionality appropriate to this place, which is better represented by Heavy Man and the Alley Kids as they are. That is, Jeremiah's dress and demeanor are ill-fit to the place (and maybe to the whole planet). Those who know Jeremiah from Scott's body of work will recognize him as a mad street preacher, unhinged and bent on saving the world by screaming at it. Here, though, he is nearly a sympathetic character, unequipped to walk through the alley, missing an arm, hapless and dumbfounded, then mercilessly attacked and knocked down. At the same time, though, he is a strange, sour-faced passerby who chooses to yell at the children who live there, responding to the Princess by pointing an accusing finger and marching toward the Kids, mouth open to tell them off. It is sad but not unexpected that they defend themselves against a strange, angry man, no matter how much someone, somehow ought to be intervening between the Princess and her targets.

As with my readings of the place itself and of Heavy Man, all of the above can be understood as a reading of the concatenation of visual signs and suggestive attributes that aggregate to support an interpretation of Jeremiah, and once that interpretation is placed beside a similarly derived reading of Heavy Man, Scott's complex themes begin to appear. The contrast between the two men—yet another kind of concatenation—is central to "Sonic Medicine," especially when we regard the piece as a variety of narrative or as a visual poem. Where Heavy Man responds to the violence of the Princess by getting heavy, Jeremiah responds to her violence with a violence of his own, attempting to wrest control of the moment from her. In Heavy Man's establishing panel, which is a little larger than Jeremiah's, Heavy Man is depicted from a distance, mostly overpowered by the scene in a way that suggests his own passive strategy of retreat and disengagement from his neighborhood. And so, in a terrific visual twist, Scott uses Heavy Man's larger panel to diminish him. Jeremiah, in his own establishing panel, is depicted in more detail, suggesting (though not yet confirming) that he is more likely to be someone who does something. Still, not even Jeremiah gets what Hollywood would call a close up. Neither man is shown in the kind of detail that might convey a very personal response to the Alley Kids rather than a habitual (instinctual, unfocused, grotesque) response. The Kids are always nearby, they are always significant, but neither man examines them closely or establishes any personal connection with them. It's as if the men are more committed to their modes of response than they are interested in the details of the situation. As a result, neither man's actions here will help either the Kids or the place. They never cross into the same space as the Kids, and they never share a panel with each other, except, arguably, in the middle of the second tier. There, Scott leaves out a few panel lines in a way that implies a connection between the fall of Heavy Man and the fall of Jeremiah. Their closest visual connection comes at the moment when each man fails alone.

In the second of the broadside's three tiers, Scott crosscuts five times between Heavy Man and Jeremiah, using panels and spaces of equal size. In doing so he turns the focus of the narrative away from the Princess and toward the responses of the two men. In the crosscutting, the men are depicted as equal, parallel in their ineffectiveness and insignificance. On the page, their actions are small in comparison to the Princess's great cloud of cussing. Heavy Man freezes and falls. Jeremiah begins to yell at the children and is repelled by a barrage of stones that, given their number and frequency, must be thrown by at least three or four of the Kids. But the Kids are offstage by now; we can't know which ones are participating and can only analyze the men. Further, the broadside shifts into a more symbolic mode with the first of these crosscut scenes, as the birds arrive and Heavy Man begins to break through the floor. The birds are like the Princess's speech in that they reach and affect both men as a living black cloud. The birds are also graphically matched to the thrown stones, suggesting visually that the birds will amplify and complete the work of the stones by repelling and silencing Jeremiah. But the birds are not the Alley Kids, or the Princess. In the middle of the second tier, the birds create a visual boundary between the men and the Kids above them in the first tier. While it may be true to say that the birds appear to protect the Kids, to do their will, or to be a manifestation of their desires, it is important to notice how everything Scott depicts, from the second tier forward, has to do with what happens to the two men rather than the Kids.

Peripheral foreshadowing foretells from the start, moreover, that the birds will do more than just knock down the mad preacher. They will also begin to lift up Heavy Man, and that action, especially—bringing an adult presence back toward the space of the Kids—goes beyond the obvious will of the Kids. The birds, then, must be more than an extension of the Princess's intentions. It is obvious that, as a visual presence and influence, the birds are at least equal to the Princess's cloud of language, and they are much like that cloud of cussing in that they are moving, ephemeral, and present but also insubstantial and temporary. Their first action, for good or ill, is to help the Kids stop the preacher, an action that echoes the way the Princess's language pushes back the resisting girl in the first tier. However, where the original scene presents an ugly mixture of disorder and apathy, the arriving birds bring a kind of aggressive order. The concerted action of the birds stands in contrast to both the isolated actions of the two men and the monovocal harangue of the Princess. Further, those birds are driven by nature and instinct, and they are arriving in this place where people's instincts and attitudes have been blunted and distorted by grotesque obsessions and attitudes. So the birds may be understood in part as a corrective force arriving from outside the physical and ideological limits of the neighborhood. By endorsing and reinforcing the counterattack of the Kids, the birds suggest the naturalness of the way the Kids respond to the sour-faced shouting of a drifter with no discernible relationship to them. The birds relieve these unchaperoned children from the unnatural burden of defending themselves against Jeremiah. By lifting Heavy Man out of the basement, the birds mark Heavy Man's retreat and passivity as unnatural, too. They return him to his communal flock, which includes these children who play and fight in the vacant lot near his house. In these ways, the actions of the birds cancel out each man's habitual grotesque pattern of response. Acting together, the birds disrupt the neighborhood's status quo.

However, the birds don't solve anything. There's dark humor in the bird metaphor. Scott, asking himself how to fix the neighborhood, arrives at the idea of a swarm of birds that falls forcefully upon problematic people, corrects their behavior, and sets events on a new course. (Imagine a swarm of birds as a solution to a few of your own daily problems and you'll begin to see the humor.) Still, there is an incompleteness to what the birds do, matched to their sketchy, incomplete bodies, and this would be a very different text if the birds brought with them a complete solution to the neighborhood’s problems. The birds don't mediate between the Alley Kids. They don't help Jeremiah come up with better ways to express his angst and anger. And they neither tell Heavy Man how to act upon rising nor raise his head-down, slump-shouldered spirits. What they do is point to, and make way for, an alternate manner of arranging things, wherein Heavy Man responds to the inner voice telling him to do something about the Kids and Jeremiah does not fill the gap left by Heavy Man by ranting at a group of children who lack both guidance from and protection by the adults in their lives. Scott uses page arrangement to underscore this idea that the birds are moving Heavy Man toward some kind of action and are forcing Jeremiah, the wrong actor for this place, to stop interfering. Heavy Man ends up occupying the right hand side of the page where Jeremiah, who acts without personal connection to the Kids, used to be. Now there is someone with some modest connection to the Kids rising into a space of action. Jeremiah ends up occupying the lefthand side of the page, where Heavy Man's inert passivity lives. What happens next is beyond the scope of "Sonic Medicine." Will Heavy Man be wise in his engagement with the neighborhood? Or will he become a hollering old man like Jeremiah has been? Either outcome is possible, as it is possible that one or more of the Alley Kids is destined to become a new Heavy Man. It's even possible to imagine that the Princess, with her pointing arm and her becrowned delusions of grandeur, will someday take the place of Jeremiah, who is also a point-and-shout kind of guy.

"Sonic Medicine" doesn't deal in the future, though. It deals in this moment of rearrangement brought on by a dose of sonic medicine. So what is the sonic medicine? The straightforward answer is that the Princess's rant, the set of sounds represented on the page here, is the medicine. Who is taking the medicine? The whole community is taking it and reacting to it, with various results. The first-stage reactions to the medicine are there in the first tier: the complicit Kids, the head-down Kid, the resisting girl, Jeremiah's outrage, Heavy Man's heaviness. And these birds, this murmuration of starlings who expose the shortcomings of Heavy Man and Jeremiah, seem to represent further effects, intended and unintended. Jeremiah's attempt to counter the Princess's rant with his own rant is a failure, a weaker medicine only adding more unpleasantness and insensitivity to an already ill situation. If success for his own sonic medicine would mean making the Princess (and the Kids) act as he would like, then not only has he failed, he has inspired the ire of several of the Kids, alienating them further from the adults in their neighborhood. Jeremiah's failure—and the effect of the Princess's medicine on him—is manifested in the way the birds knock him down. Heavy Man, meanwhile, is confronted with the kids yelling, then with Jeremiah yelling at the kids, then with the illness of the way he, as a neighborhood adult, retreats into his own sense of inefficacy, leaving behind the void that Jeremiah fills so poorly. All this medicine makes Heavy Man heavy and makes him fall, but as the birds represent a second stage in Jeremiah's reaction to the medicine, they represent a second stage, too, for Heavy Man, who is finally pulled back toward the children not by shouting but by, suggestively, a murmuration.

The birds rearrange things so as to cancel out the habitual grotesque responses of the two men and create conditions for a new kind of action in the neighborhood. Ironically, the vileness of the Princess may be doing the community some good, inspiring self reflection and new kinds of action. Scott implies that each man ought to reconsider what he is doing to, for, and in this neighborhood. What kind of a space are they making for these Kids? It's not a good one. They could do better. Seen from this angle, the ranting of the Princess works as a a medicinal corrective in the grotesque heart of each man, and the work the medicinal rant does is made metaphorically manifest by the actions of the birds. The birds illuminate not solutions, exactly, but unconsidered or unexploited possibilities, murmurations from another, similar world. What if Heavy Man interacted with the Kids? What if Jeremiah left them alone? What if the Kids could be kept from endlessly replaying the unhealthy actions and attitudes they have learned by living in this place as it is? Though the Princess may help them see new possibilities, Scott doesn't suggest so much that her ranting is a good thing as that it can be medicinal. Taking too much medicine can lead to overdoses, with awful consequences. That's obviously the case with this sonic medicine, which promises, as a long term solution, nothing good for this neighborhood or these children—only endless repetitions of the avoidance and violence already present in the neighborhood. Once again, the possibly horrific long term consequences of the Princess's medicine are manifest nicely in the bird metaphor. A murmuration of starlings can be beautiful, but it can also be alarming. If the flock actually moved into the yard and stayed there for long, then its effects would be as grotesque and destructive as anything the current residents are doing. We need a little medicine, but not an addiction.

Kolbo Literary

My reading began by noting Scott's visual analytical focus on a kind of place, a set of grotesques, and a set of responses. The reading moves from there by considering themes and meanings that emerge from the more complex visual juxtapositions on the page. I don't think I've reached the bottom of "Sonic Medicine," or that I've asked and answered every question worth asking and answering about the piece. For example, I didn't ask why the Princess particularly targets the boy with his head down, who could be a neo-Heavy Man in training. I didn't consider at length what might be said about the ages of these characters, or about their genders. I didn't consider the use of color in the broadside. There are remaining questions to be asked about other juxtapositions on the page, too. For example: Is there something more to say about the way that, just as Heavy Man and Jeremiah are linked by gender and page position, the Princess and the resisting girl are linked by gender and page position, and are further linked by clothing color and by the fact that they wear clothes marked as feminine (a dress, a skirt)? Like the questions I do explore in more detail above, these are the sorts of questions that emerge when readers of visual narratives look closely at the details (visual and otherwise) and ask how their initial responses are affirmed or undercut by what they see. These are the sorts of questions (and evidence-backed answers) that emerge when we look hard at a comic.