Authorship on Canvas LMS

Canvas is a popular learning management service (LMS), or educational technology platform that institutions purchase or adopt that enables students, administrators, educational staff, and instructors to exchange information. For instance, an instructor might post course readings for students to access and assign grades within an LMS, while students upload assignment drafts or participate in discussion forums where they discuss course readings. In examining Canvas's terms of use and privacy policies, we want to acknowledge that these policies are some of the best we've seen from a platform provider. Still, we want to offer a critical investigation of authorship issues associated with using an LMS for two reasons: (1) these platforms are ubiquitous in educational settings today and (2) LMSs provide gateways where parties beyond a student, an instructor, an institution, and the LMS platform provider can access inputs.

LMSs, as web-based platforms, make use of tracking tools that store user data and metadata, much of which is invisible to student users and even to instructors. Let's specifically consider Canvas's "Instructure Privacy Policy." Analysis of this policy demonstrates that the platform draws a distinction between "Data You Provide to Us" and "Data Collected Via Technology" before concretely noting that it deploys cookies, web beacons, flash cookies, and analytics to gather information about users. While students understand that when they input information requested by Canvas such as first and last name, gender, email and mailing addresses, the data may be stored and used by Canvas, they may not realize that other, less visible data, including "information regarding the date and time of your visit and the solutions and information for which you searched and which you viewed," is being collected and stored. The policy also notes that Canvas retains information such as "files and messages that you store using your account." Further, the policy language fails to offer detailed insight about how the platform might make use of the data and information it collects. The information collected is not displayed to nor used by students or instructors; rather it serves to benefit Canvas by allowing for development of their products, for targeted advertising that brings in revenue, and for agreements with third parties who have an interest in such amassed information.

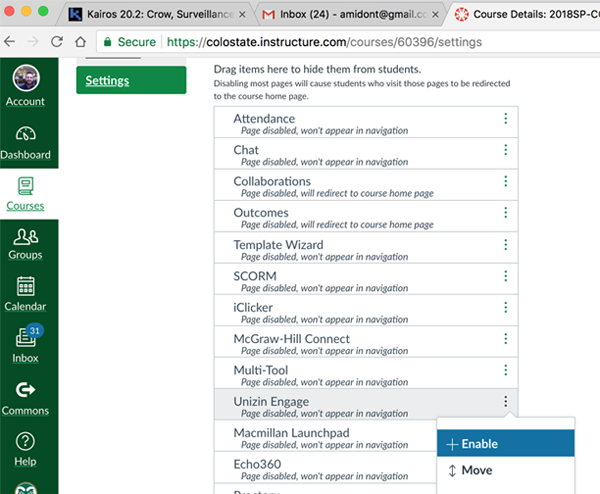

The point that we want to stress here is that LMSs are not simply neutral channels through which content, data, and metadata flow within institutions and between students, instructors, and administrators. LMSs also function as gateways that connect students' intellectual property, information, and data with platform developers and with third-party tools and applications. Developers make use of the Learning Tools Interoperability (LTI) standard to embed third-party tools directly within LMSs, granting access to the networks of activity and associated IP that are generated within schools and colleges. LTI can be useful for universities because it helps educators, students, and administrators select and integrate tools and services that they might find valuable. For example, at Tim Amidon's home institution, Colorado State University, instructors might choose from a range of plugin tools, including Unizin Engage, McGraw-Hill Connect, and Pearson MyLab (see Figure 13 for a screen capture of tools available for integration within Canvas via LTI).

Many educators at CSU find these types of tools exciting because they offer new and valuable ways of understanding how we learn and teach. Some of Tim's colleagues, for instance, have been using a learning analytics tool called Unizin Engage to better understand how students are engaging with course materials. As Unizin puts it, "Engage provides insights into how students are using content. Instructors can quickly see which students have questions and how often they are interacting with the text." Another example of a learning analytics tool that Kairos audiences might be familiar with is Eli Review, which Jeff Grabill, Bill Hart-Davidson, and Mike McLeod developed "to support evidence-based teaching practices and facilitate rich peer learning environments." Learning analytics tools such as these can be used to better understand how learning and teaching unfolds by offering educators, students, and administrators new windows through which to view educational practices. However, educators, students, and administrators need to not only understand who receives and has access to the content, data, and metadata they generate within these platforms (especially learning analytics platforms that are seamlessly integrated into robust LMSs), but also to understand how university agents, platforms, and third parties beyond universities and platforms might use the IP students and educators have contributed to these platforms.

| Category | Category Attributes |

|---|---|

| Users | Students; graduate teaching assistants; instructors; faculty, program, department, and institutional administrators; academic support staff; athletics director; tutors; agents of the institution; LTIs (plugin third party applications); consortia members; platform employees and staff. |

| Permissions | Instructors or programmatic, department,

and/or institutional administrators adopt the

LMS and compel students to use the platform as

condition of participation in course. Click-wrap agreement where student agrees to platform terms of use. Policies such as end-user license agreements (EULAs), as well as platform specific copyright and privacy policies govern use. Instructors and/or program, department, and/or university administrators may adopt or integrate third-party tools which plug into the LMS, requiring students to view additional click-wrap agreements that enter students into terms of service, EULAs, and platforms' policies that govern copyright and privacy on platforms. |

| Inputs | Surface contributions:

Student assignments, course assignments,

readings/PDFs/course texts, links to content

hosted on external platforms (e.g., YouTube

videos), discussion forums, direct

messages/emails, announcements/replies,

schedule. Nontransparent and hidden contributions: Data and metadata about interactivity, including when students/instructors have uploaded/downloaded content types, assignments, files, when students submit, if submissions are late, how much time students have spent logged in, how many of the files have been downloaded by students, how much time students have spent watching embedded videos within the platform, file types and file metadata, IP address, student name, student grades, interactivity/behavior within website, geolocation, browser, and hardware used. |

| Operations | Platform facilitates student-to-student and

student-to-instructor interactions. Data about interactions is captured and logged within a database. Algorithms are applied to data to reveal insights about student learning behaviors, individual and group student performance and engagement levels, and/or perform student, instructional, and programmatic assessment. Learning tools interoperability standards facilitate ability for instructors and administrators to integrate external tools for use in courses and programs within universities and schools, allowing content, data, and metadata to flow from universities and schools to tertiary platforms. |

| Outputs | Insights on learning behaviors at individual

and aggregate levels. Insights about how instructors and students use tools/platforms, including which types of content are interacted with and how. Databases of content, data, and metadata uploaded to/passing through the site. Proprietary algorithms trained using database. |

| Gateways | Once LMS is adopted, students and instructors

have ability to upload and interact with content

within LMS, as well as with additional platforms

integrated into LMS through LTI standards.

However, students/instructors must agree to

secondary/tertiary EULA agreements (e.g., a PDS

integrated within Canvas gives appearance that a

user has never left LMS, but is now working

within a secondary/tertiary platform). Teachers and administrators have ability to observe/view analytics data about student performance and behaviors within LMS. De-identified data can be scraped and mined from classes or LTI plugins for institutional research, consortia level research/planning, usability testing of learning applications/tools, as well as to garner insight into trends about how students behave/learn (e.g., engagement research conducted by programs, departments, universities, consortia, platforms, and/or platform-institution or platform-individual collaborations. |

There are ethical and important reasons for educators to employ learning technologies that make use of student data. Indeed, Grabill observed, in his 2016 keynote address at the Computers and Writing Conference, "The work that others are doing with technologies for learning to write has the potential to impact millions of learners." Yet he also took a moment to reflect on the potential implications of failing to attend to the exchange economies that impact how IP circulates within educational technology platforms. He noted how various platforms can be wielded toward very disparate ends in our schools: "One of the most insidious moves in education technology in K-12...is schools' penchant for free on the surface, which costs them dearly downstream particularly taking its toll on the lives of teachers and the lives of students." While the seamless integration of educational technologies into schools and interoperability of third-party applications within LMSs present opportunities for the improvement of teaching and learning, more frequently those partnerships and agreements result in an appropriation of student IP for the benefit of a platform developer or third party rather than for instructors or students.

In other words, learning management systems and the educational technology and learning analytics tools that can be plugged into them have great potential precisely because "of how easily they can harvest our intellectual property, data, and the minute details of our lives" (Morris & Stommel, 2017). LMSs, as tools designed to facilitate and amplify the flow of IP created by students both within universities and to tertiary markets, users, and audiences, are worth critically interrogating for the ways they participate in and reify power dynamics within IP exchange economies. LMSs directly and indirectly enact asymmetrical power relationships in the exchange of information. Resigning control of student intellectual property by enabling wide and uncontrolled access creates an asymmetrical power relationship between powerless intellectual property creators (students) and powerful data brokers (technology developers and educational technology companies).

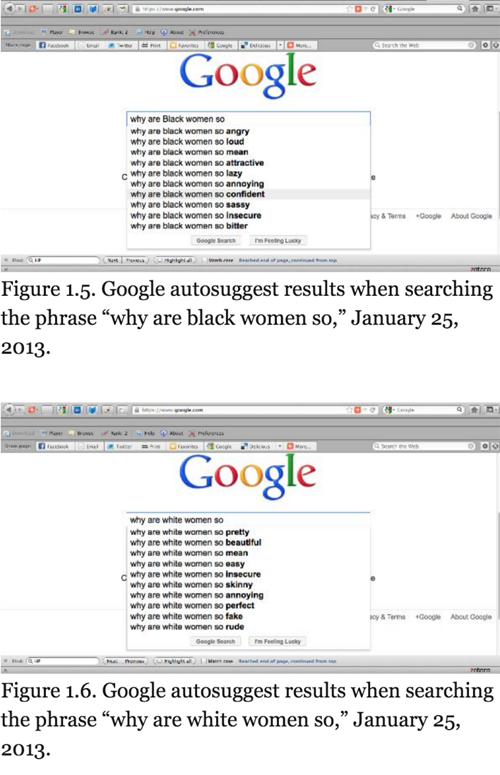

This power dynamic might be seen as another instance of inequity resulting in part from disproportionate levels of access to and control of the benefits of education according to class, racial, ethnic, geographic, gender, and cultural makeup. Resigning control of the IP inputs that students make means giving entities outside of our schools access to valuable student data. These data can be used to support both local and external surveillance regimes, and further disenfranchise those who have been historically most subjected to social, cultural, and economic marginalization. According to Safiya Umoja Noble (2018) "discrimination is...embedded into computer code and, increasingly, in artificial intelligence technologies" (p. 1). In her monograph, Algorithms of Oppression, Noble provided a detailed analysis of how Google's algorithms reflect the types of misogynist and racial bias that exist with society, as algorithms learn to return results based on the data users input into its platform and assumptions that algorithm designers make about what those inputs might suggest.

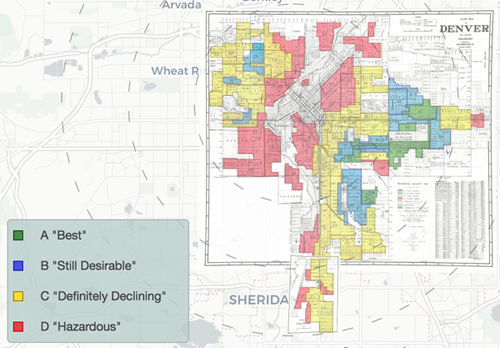

Educational technologies are not different from the logics and use contexts which influence platform design and use in our everyday lives. Educators, in particular, must be aware of the ways that bias and discriminatory practice may enter into education technologies, as Chris Gilliard and Hugh Culik (2016) argued, because they can be used to engage in digital redlining which seeks to "reinforce existing class structures." As Gilliard and Culik posited: "in one era, redlining created differences in physical access to schools, libraries, and home ownership. Now, the task is to recognize how digital redlining is integrated into edtech to produce the same kinds of discriminatory results."

Indeed, in their analysis of acceptable use policies promulgated at over 30 universities, Gillard and Culik discovered that Carnegie classifications directly correlated with how universities defined and conceptualized acceptable use. "These deeply different approaches to digital technologies," Gilliard and Culik observed, "discourage and limit working class students from the open-ended inquiry supported at more elite institutions." We share these concerns, and computers and writing specialists, digital rhetoricans, and digital humanists have much to contribute to critical conversations about these tools. Returning to Grabill's keynote, it's important that, as a matter of stance, we engage with these tools and be critical of them.

Responding to the ways that inequities materialize in digital environments, platforms, and spaces has been a central tenet of our disciplinary history. What we find most concerning about LMSs, as IP scholars, is how complacent students, instructors, administrators, and platform users have become about these asymmetrical exchange and control dynamics. It often seems as if educational stakeholders do not realize—or care to realize?—that the student IP created and composed with these platforms generates vast forms of wealth, knowledge, and value.

We worry that students, instructors, and administrators may not recognize that they are no longer working within an LMS like Canvas when they use a third-party application embedded within the system, an application that appropriates IP generated by both students and faculty. We worry that so many of our students question neither our requests for them to use various tools nor the terms of use governing control over the IP they will contribute to or compose within those platforms. We worry that many users may not realize that they are not only granting LMS platforms like Canvas access to their IP, but also—when they interact with other third-party tools plugged into an LMS—granting access to other downstream parties. We worry, further, that school administrators and educators are not acting as responsible stewards of students' educational records when they freely release volumes of mineable metadata, data, and content downstream without deeply considering how those data streams might be recomposed in the future. Indeed, the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) argued that "[t]he pool of data potentially available to ed tech providers is more revealing than traditional academic records, and can paint a picture of students' activities and habits that was not available before" (2017, p. 24). However, we worry most about the cumulative effect of the pedagogical practices surrounding LMSs: Have students and instructors alike been conditioned to work from the default position that the ideas they think, the texts they compose, and the data that they generate are something that they simply do not or should not have control over?