Copyright, Content, and Control

Student Authorship across Educational Technology Platforms

Timothy R. Amidon, Les Hutchinson, TyAnna Herrington, and Jessica Reyman

This section of our webtext was composed by one co-author, TyAnna Herrington, shortly before she passed away. We present these words as written and without further editing to honor her contribution to this project. This section details legal foundations for copyright protections in the United States, with special attention given to the rights of college and university students as authors. It is our hope that the legal provisions and case law outlined here will provide the background information needed to better understand the challenges presented by educational technology platforms to student authorship. As TyAnna notes below, despite legal rights that students could have, including the same copyright protections for their contributions as any other author, “common practice is to treat student work as if [their work] is unprotected.”

The U.S. Constitution's Intellectual Property Clause

The U.S. Constitution's Intellectual Property Clause (U.S. Constitution. Art. 1, sec. 8, cl. 8.) makes knowledge advancement and innovation its primary goal, but creates incentive for authors to create by providing them with rights, though limited, to benefit from the works they create (see Herrington, 2010a, pp. 12-17; Patterson, 1987; Patterson & Lindberg, 1991). Beyond this acknowledgement of authorship’s importance for advancing education and innovation, authorship and its representative quality for the individual creating authored work, is also necessary and encouraged as a means to support speech that represents the individuals who create it. Authored works embody thoughts and expressions and allow authors to participate in national conversations, whether the mechanism involves texts, images, sounds, or any other numerous manifestations of communication and influence.

In essence, authorship provides individuals with access to the national community and provides a voice and means to participate in the nation's conversations, shaping what we are as a country, what we might be, and creating opportunity for reshaping what we've been in the past.

The statutory law provides a means for participation, protecting authors and, as much as possible, ensuring that they benefit from their works, but also providing a structure in fair use and in free speech law to support access for the public to information that informs us about developments within the country that affect our lives and access to materials and information on which we are able to build to express new ideas, create new products, and generate discussions that shape our future. Only those who have access to a public domain of national information can participate. To enable democracy and to simultaneously enable innovation and education, we must maintain the balance described in the Constitution's intellectual property provision, enabled by a well-functioning statutory base.

The statutory law in the 1976 Copyright Act, which is still controlling law today, delineates the steps for creating authorship, the first step to expression, public voice, potential benefits, and rights to protect, use display, and disseminate work, as well as preventing others from doing so, among other benefits.

The Copyright Act of 1976 and Student Authorship

To author a work, until the 1976 Copyright Act, required a natural person to create an original work that was recognizable as original and created by the individual claiming authorship. If authors wanted to claim copyrights to their work, which would allow protection against infringement and federal recognition of the claim of authorship among accompanying benefits, they would have to engage in active pursuit of the copyright by filing and receiving the copyright through the federal copyright office (then of the Patent and Trademark Office, or PTO).

After the enactment of the 1976 Copyright Act in 1978, copyright is created automatically by any author who produces an original work that is "fixed in a tangible means of expression," which essentially means that the work is perceivable and recognizable as unique. Since copyright is created automatically, authors who prefer that their work be accessible in the public domain must make the effort to license the work to the public. This means that after the 1976 Act was enacted, the public domain immediately shrunk.

What was inhibiting for the public, could be beneficial to individual authors who, prior to this version of the Act, were not apprised of the law and its function, would find their work immediately protected. This aspect of the law can be significant for students, who may not consider the potential value of the work they create and might not think about protecting it. Under current law, they are not required to take steps to protect their authored works, although gaining a copyright registration is recommended for the multiple benefits it provides.

This means that student-authored works are copyrighted like any other authors' works and students' rights in those works exist in the same way that any other authors' works do. Regardless, it is not uncommon that student-created work is treated as if it is legally unprotected and students' rights to make choices about how to treat their work can be disregarded. Even Jenny Chou, a graduate student at University of Chicago who had participated fully in authoring a patentable product, was treated as if her work as a student was of no value. After completing the patentable product, her academic advisor shut Chou out of the patent application process and left her name off the list of authors. The law, which supports student authorship even when educators do not, requires that all authors' names be listed on a patent application to obtain a valid patent. Since Jenny Chou's name was not listed, the PTO invalidated the patent.

Students who work in service-learning based classes often are asked to create content for the service-learning client but are stripped of rights to claim copyright to their contributions when they sign agreements relinquishing control of the work. Students face the choice of not taking the course or possibly providing work without compensation. In addition, when students contract with service-learning clients on the basis of a preset agreement from an instructor, they often do so without power to negotiate a contract, but sign off because they have to as a means to complete a course. These contracts can operate as adhesion contracts which force a contractor to agree to the terms that are already set, simply as a means to accomplish what has to be completed. Whether adhesion contracts are enforceable has not been clearly decided through legal practice and this complicated area of law can lead to long, drawn-out legal battles that inhibit the overall goals of parties involved. The question of force plays out less in adhesion contracts themselves, but more in actions from educators who force students to sign adhesion contracts. The first level of choice is taken away for those students who contract against their will, at their university or instructors' demands, and the second, when adhesion contracts that they're forced to enter into give students no power to negotiate what they sign. Educators could eliminate the problem with adhesion contracts if they stopped forcing students to enter them.

Arguably, some of these approaches are based on sound pedagogical practices that provide students with real-life experiential learning and broaden their ability to develop and test communication skills and practices. They learn what they never could by merely sitting at a desk each class period, either listening to instruction or writing texts that are never read by anyone other than the instructor. Still, many students have no choice but to take classes that they wouldn't agree to take if others fit their class schedules, or they might take classes that are required for a degree and always require that students provide intellectual products without choice or compensation. But statutory copyright law creates copyrights in students' work as it does for other authors and under the law, students have a right to

- copy the work

- create a derivative work from the original

- distribute the work

- perform the work

- display the work

- and, perhaps most important, prevent others from doing all of the above. (17 U.S. Code § 106 - Exclusive rights in copyrighted works)

These rights legally empower students to refuse to provide work without permission, yet common practice is to treat student work as if it is unprotected.

Fair Use Doctrine

Fair Use is an affirmative defense against copyright infringement, that echoes the statutory language of the U.S. Constitution's Intellectual Property Clause that demands that we maintain a public domain to support learning, innovation, free speech and democratic participation as a means, in conjunction with other aspects of the Constitution, in particular free speech rights, to maintain a robust democracy. The Eldred v. Ashcroft (2003) case, which concluded by allowing yet another 20-year extension of the copyright term to stand, making the term of copyright protection life of the author plus 70 years and for corporate "authorship," publication plus 95 years, left us with little access to a public domain except for use of fair use or the 1st Amendment, so the Court constitutionalized fair use through acknowledging its joint role as protectorate of constitutional interest in a public domain in conjunction with that of the 1st Amendment (see Herrington, 2010b). On this basis, fair use is necessary to ensure that we have a functioning democracy and without access to work for purposes of supporting speech, news reporting, education, scholarship, and development of new ideas we could not progress or function democratically.

The affirmative defense of fair use begins with an admission to whatever legal offense is charged, but excuses the offense with the support of the law. Fair use is a part of the copyright law that excuses use of a copyright holder's or holders' work by demonstrating that the use satisfies four factors that characterize the use. Transformation comes from case law that takes into consideration ways that the four factors generally point to a form of the original work that is transformed. The Perfect 10, Inc. v. Amazon.com, Inc., (2007) case and AV ex. rel v. iParadigms Llc., case (2009), in following its lead, scoop transformative use into that characterization.

The four factors are

- the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes; [A work that is educational rather than commercial, for example, is more likely to be excused by fair use.]

- the nature of the work; [If the work the user is creating is for a broader societal purpose, for speech or other constitutional goals, it is more likely to be excused by fair use.]

- the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; [If the amount of the work used is small but is the most substantial portion of the whole of the used work, the use is less likely to be supported by fair use.] and

- the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work. [If the use of the work creates a copy that could stand in the stead of the original and be marketed instead of the original to buyers who would consider it the same, the use is less likely to be excused under fair use.] (17 U. S. C. § 107 (1978)

All four factors of the fair use exception have to be considered in conjunction to make a determination whether an infringement may be excused.

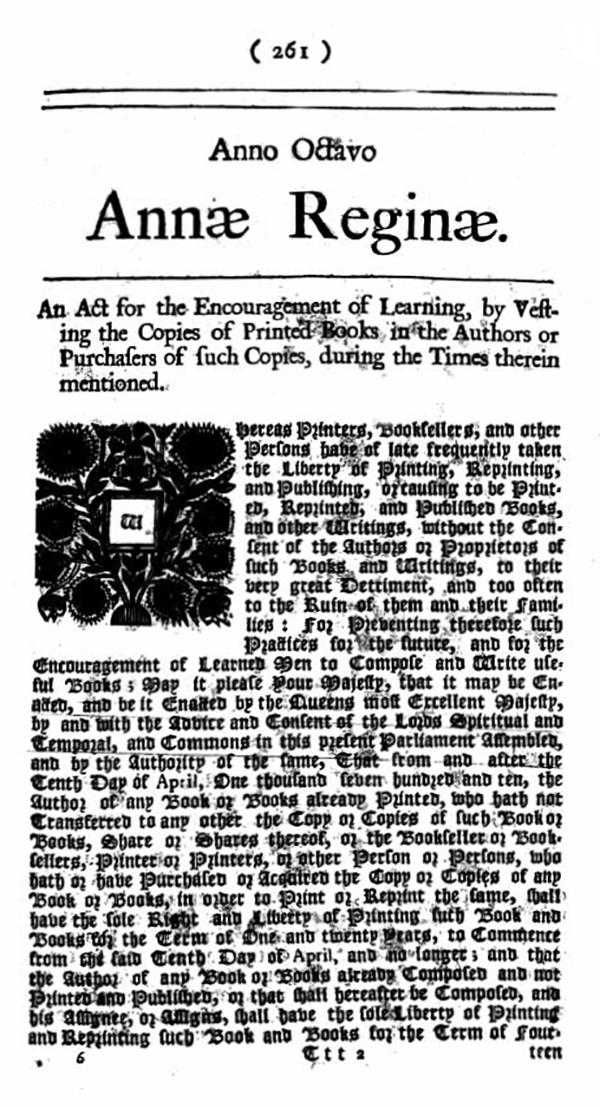

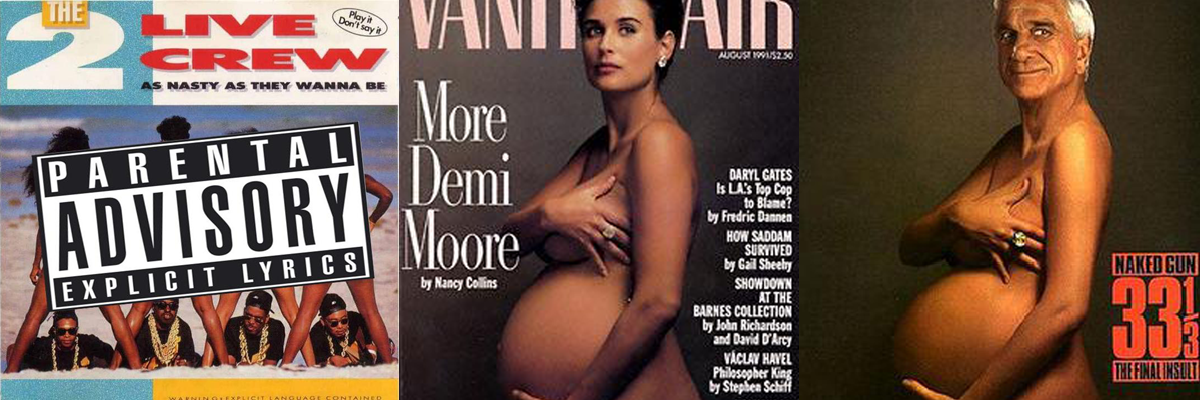

The significant cases in fair use include Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc. (1994), which some claim is the first transformation case, in which 2 Live Crew created their own version of Roy Orbison's song, "Oh, Pretty Woman," changing the lyrics, the musical structure and presentation, and most significantly, according the Supreme Court, engaging in commentary to point to the banality of Roy Orbison's song. Justice Souter, writing for the Court noted that "It is uncontested here that 2 Live Crew's song would be an infringement of Acuff Rose's rights in "Oh, Pretty Woman," under the Copyright Act of 1976, 17 U.S.C. § 106 (1988 ed. and Supp. IV), but for a finding of fair use through parody. From the infancy of copyright protection, some opportunity for fair use of copyrighted materials has been thought necessary to fulfill copyright's very purpose, "[t]o promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts . . . ." U. S. Const., Art. I, § 8, cl. 8. " The Court noted, regarding transformation specifically, that “Suffice it to say now [ . . .] parody has an obvious claim to transformative value, as Acuff Rose itself does not deny."

Similarly in Liebovitz v. Paramount Pictures, Corp. (1998), the court declared that after nationwide public argument over whether to declare the beauty of or inappropriateness of Annie Leibovitz's photo of a nude, pregnant Demi Moore on the cover of Vanity Fair(17 U. S. C. § 107 (1978)), Paramount Pictures' poster of the same photo superimposed with Leslie Nielson's face, was fair use. The court found that the image included commentary in the smirk on Leslie Nielson's face and the extra-large bling-ring on his finger, that acted as a comment treating the national discussion. The work was also sufficiently transformed that no-one would confuse the copy from the original.

Where these two cases were determined in great part by the speech content of the copied images, other cases that focus on transformation but on elements of fair use beyond speech, include Bill Graham Archives v. Dorling Kindersley Ltd. (2006), in which the publisher, Dorling Kindersley (DK), produced a graphically intensive book called Grateful Dead: The Illustrated Trip, which was a cultural treatise on the history and culture of the Grateful Dead and the 1960s-70s. The book used the artful, highly colorful and intricate illustrated posters that Bill Graham Archives had created to advertise the band and its tours, and cut them to page-size to include. The court, in part, considered the educational purpose of DK's book, as well as the transformative nature of cutting the poster to book page size, noting the transformation of the original to hold in favor of DK. An educational purpose still reflects the constitutional intention to support education and learning, in this case, through a historical perspective.

Kelly v. Arriba Soft Corp., (2002) is somewhat similar and goes a step further to pure practical transformation in treating a claim by Kelly that Arriba Soft infringed its copyrights by copying complete images of its photos. Arriba Soft had transformed the images into thumbnails and included them in its database with links to the websites in which the original photos were for sale. The images themselves were transformed rather than any claim of transformative use.

Leading cases in which transformation is used to excuse infringement are consistently based on transformation of the expression itself rather than use of an expression. They are consistently tied to other fair use factors that support constitutional intent.

The statutory law in the 1976 Copyright Act, which is still controlling law today [as of Fall 2018], delineates the steps for creating authorship, the first step to expression, public voice, potential benefits, and rights to protect, use display, and disseminate work, as well as preventing others from doing so, among other benefits.

Students' Work as/and Work for Hire

Another area of intellectual property law resulting from the passage and enactment of the 1976 Copyright Act, is work for hire in its current form, relying on 12 elements of agency partnership law to determine employment status for work for hire. The 1976 Act replaced the 1909 Copyright Act which had used "control of the hiring party" to determine who could claim copyright, created a legal fiction of corporate authorship through work for hire.

To determine whether the law creates a work for hire in a product created by a hired party, based on the 1976 Act, agency and partnership law's 12 elements that determine employee status have to be applied and analyzed, then it has to be determined whether the hired party was working within the scope of duties. Both of these elements have to be satisfied to decide employee status and all 12 elements have to be considered to make a determination of employee status. Using one or two elements alone cannot indicate employee status.

- The hiring party's right to control the manner and means by which the product is accomplished. The more control, the more likely this element is to support employee status.

- The level of skill required. The more skill hired parties have the more likely they are considered independent contractors.

- Whether the hired party or hiring party provides tools and supplies. If the hiring party provides tools and supplies, the hired party is more likely to be an employee.

- The right to control the location of the work. If the location of the work is at the hiring party's business, the hired party is more likely to be an employee.

- The duration of the relationship between the parties. If the duration of the relationship between the parties is continual the hired party is more likely to be an employee, but the relationship can be long-term but not continual, where the hired party provides work in response to multiple jobs, and still be an independent contractor.

- Whether the hiring party has the right to assign additional projects to the hired party. If a hiring party has a right to assign additional projects to the hired party, the hired party is more likely to be an employee.

- The extent of the hired party's control over when and how long to work. When hired parties have more control over when and how long to work, the more likely they are to be independent contractors.

- The method of payment. When hired parties are paid one time or in two or three installments rather than receiving a weekly or monthly paycheck, the more likely it is that they are independent contractors.

- The hired parties have [agency] in hiring and paying. The more likely it is that hired parties are independent contractors when they hire and pay their own assistants.

- Whether the hiring party is in business at all. If the hiring party is not in business at all, it is less likely that the hired party is an employee.

- Whether the hired party receives employee benefits such as insurance and retirement. Hired parties who receive employee benefits are more likely to be employees.

- Whether the hired party is taxed as an employee or independent contractor. When hired parties are taxed as employees they are more likely to be employees.

To establish whether an employee is working within the scope of duties, it is possible to use one or the other of the following tests:

Three-point test

- Was the work produced at the hiring party's place of business?

- Was the work created during the hiring party's set working hours?

- Was the work produced at the employer's demand?

Two-point test

- What are the established requirements of the job?

- Does the work fall within those requirements?

Students may do multiple kinds of work on campus, sometimes as employees, and sometimes as students. Those in positions of authority on campus should be aware of and careful about how to treat the work that students create, and these 12 elements and scope tests can help determine whether students are working as employees or as students.

If students create work for the university specifically to make money and not to achieve a grade, depending on the situation in the categories above, they are more likely to be treated legally as employees. Students who engage in true employment on campus are also likely to have signed a contract noting that they agree to act as an employee. But difficulty arises when they participate in a class or a club in which they provide content that may have value they did not expect or may assume that they will keep after the period of engagement and find that someone or some entity makes a claim on that work.

Disclaimers

The information and ideas contained in this webtext are not intended to be understood as legal advice, but rather as an exploration of the potential tensions that may exist between how authorship functions as a legal concept and how authorship is practiced and theorized in educational contexts.

Webtext design adapted from © Escape Velocity by HTML5 UP under a Creative Commons CC BY 3.0 license.