My Life as a Language Funnel

Finally, the fateful day came.

I found myself in a dingy little

office with peeling wallpaper,

staring wide-eyed into the face of my new daughter. She was beautiful.

Dirty, with a noticeable limp and a shaved head, her body covered with

a scabby rash and about two sizes too small for her age -- but unquestionably

beautiful and beaming with intelligence. My husband and I were stunned.

Our translator, who had visited Lena and became a special friend to her,

plopped her into my lap. I took her hand in mine, and at the sight of

her slender

fingers spread across my palm, burst into tears of joy. Lena gazed questioningly

at my face, and I smiled and cued my first words to her, “I am not

sad.”

A few moments later, as she played on the floor, a poster of a baby’s face caught her eye. Smiling a black-toothed grin, she pointed it out to me.

“Baby,” I cued. “Baby,” she cued in imitation. My husband and I looked at each other in amazement. From then on, every moment spent with Lena was heavy with the potential to cram language into her. There was no time to lose – how many short months would she remain in the “language sponge” stage of development?

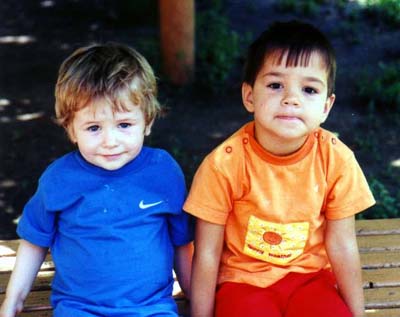

After the meeting with Lena, we drove to the orphanage’s infirmary, where less thriving children stayed. There we met our second daughter, a three-year-old blonde whose tiny frame was what amazed us most about her. Weighing about seventeen pounds, Dasha looked like an eighteen-month-old baby. She had a hugely bloated (distended) belly and spindly little legs. Her feet were baby size four. The orphanage worker held Dasha in her arms, looking dazed and a little frightened. Using a beanie baby pig we had brought, the woman asked Dasha in Russian to point to the various body parts. This she did with pride, and then clutched the pig in a surprisingly strong grip, seemingly ready to fight if we tried to take it away from her. It was the receptive language, above all, that let me know: she was tiny, but mentally there was something waiting and needing to grow.

When we got the two girls back to our host home, their respective hungers were immediately evident. Dasha sat down at the kitchen table in front of a bowl of good food, and we began to shovel it into her mouth. If we tried to move the bowl, she grabbed it and literally growled at us. For two or three months she ate like this, almost constantly, cramming giant bites into her mouth one after the other. If she saw one of us eating, she would open her mouth wide, point her finger down her throat, and moan, “Ahh! Ahh!” Dasha was starving.

Lena, on the other hand, seemed to need less food. Abandoned at two, her body had gotten much of the infant nutrition Dasha missed. Within a day or two, she actually became picky, and outright refused to eat borscht, the cabbage soup she had daily at the orphanage. Lena’s hunger lay in another part of her being altogether. It emerged at night when she screamed nonstop and refused to sleep unless I lay down with her and make unbroken, direct eye contact until she drifted off. If I closed my eyes before she did, she panicked. What Lena was starving for was a human connection, language and communication.

The next year was the most intense I’ve ever spent as a teacher of English. While other children her age were speaking in complex sentences and beginning to use abstract concepts, Lena had yet to understand her first word, much less use it. Dasha, too, was greatly delayed in language development, arriving in our family with maybe fifty words of Russian in her expressive vocabulary. I began immediately to cue everything I said to the girls, and to talk to them constantly, naming for them time and time again the objects and actions of everyday life. For Lena, particularly, life became an intensive language lab. I named her clothing as I dressed her, her food and utensils as I served her lunch, her toys before she was allowed to play with them, and her body parts as I bathed them. I structured our daily activities such as meals, bath time, and bedtime so that they became language lessons, in addition to a longer, more formal lesson each day when Dasha took her nap. Lena was parched for language and meaning. Sometimes it was hard to get her to look as much as I wanted her to. She was, after all, four years old. As one might expect from an institutionalized child -- or any child, for that matter -- she had a few normal, four-year-old tantrums, but she never burned out when it came to learning language, never tired of it. I kept meticulous records of every word she clearly understood.

Soon she could understand a few hundred words of various kinds: nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, and directional words. Because our goal from the beginning was to educate our children so that they could become as literate as possible, I carefully chose a curriculum to begin home schooling in their preschool years. My choice was the Core Knowledge Curriculum, which developed out of E.D. Hirsch’s cultural literacy campaign. There were several Core Knowledge preschool curriculums posted online by generous and hard-working teachers, so I began downloading two of the most useful ones for preschool language: the nursery rhyme-per-week and the letter-a-week curriculums by Laura Smolkin in Orlando, Florida. I would strap Lena into a high chair so she had to watch me, and while she ate breakfast, I cued nursery rhymes over and over again, acting them out with toys and pictures. Using sign, this could never have been an option. For one thing, the rhythm of speech and singsong rhymes which children find enchanting in traditional nursery rhymes are entirely inaccessible to a profoundly deaf child using ASL. Cued speech makes both of those qualities of oral language accessible and visible. In fact, it may be easier to detect rhyme with cued speech, for both hearing and deaf children, because of the visual emphasis.

Before she could have any of her favorite foods, she had to watch me cue their names and descriptions of them, and once she was able, she had to ask for them by cueing politely to me. "Eat" soon became "cereal," "peanut butter," or "tea and honey," and that soon progressed to "Cheerios," "Smacks," or "Pops." The progression of her language development was the same as any other child who is learning English through hearing.

Although cueing was much easier for me than signing would have been, and I was able to use much more complex and varied language almost immediately and with confidence, it was still more than full-time work. It was constant, desperate work at nearly every waking hour. Dasha, our hearing daughter, absorbed language literally out of thin air. Within a month she could speak the first 100 words of English that it took Lena three months to master only receptively via cues. This is not because of any difficulty inherent in cued speech. It was because nearly all of Lena's language came solely from me. My husband had a hard time learning the system, and it took almost the entire school year to secure a cued speech transliterator for Lena's school. Dasha got language wherever she went, without even trying. Lena had to stop whatever she was doing and look specifically at me. (Fortunately for us, Lena's wonderful preschool teacher, audiologist, and speech therapist in her Prince George's County, Maryland school learned to cue about halfway through the year, and after that could communicate directly with her in the mode of English used at home, easing the pressure on me considerably.) Once it took root, however, Lena's receptive language exploded, and after a year it got easier and more natural all the time. Expressive language took much longer, however, and is still a crucial area for development. But we have come so far in only eighteen months. Now, Lena can cue to me, "I want Smacks, please. No milk." She can understand when I ask her "What letter of the alphabet does Smacks start with?" or "What's the first sound in Ssssssmacks?" -- and most of the time she can give me a correct answer! I feel confident that I can say just about the same thing to Lena as to Dasha, and both girls will understand equally well. In fact, there are some concepts that Lena understands receptively for which Dasha is not developmentally ready.

The following are links to several threads of an online discussion on Lena's language development, spanning from shortly before the adoption to the present. Other parents and various deaf education professionals had comments and advice to offer over the course of the first year and a half:

Adopting

Deaf Preschooler:

http://cuedspeech.com/discussions/

thread.cfm?threadid=91&messages=5

Adopted Deaf Preschooler:

http://cuedspeech.com/discussions/

thread.cfm?threadid=103&messages=3

Cue Kids and Reading:

http://cuedspeech.com/discussions/

thread.cfm?threadid=125&messages=6

Silent Cue Kid:

http://cuedspeech.com/discussions/

thread.cfm?threadid=138&messages=5

Without Cued Speech, I could never have done this with the ease of natural, native language. Since I am a native English speaker, I had the language already for all the actions and things that Lena wanted to know about, and I knew the sounds of all the letters to teach her as we learned the alphabet. If I had gone with sign, I would have needed to spend valuable time learning a new language instead of playing with and teaching my new daughters a language I already knew. I would have had to stop communicating with her to look up signs I did not know. Soon, Lena's ASL skill, from constant exposure at school, would have surpassed mine, and what I could teach her would have been severely limited by my language ability.

On

to: The Cochlear Implant Controversy