Sketching-to-Learn (as an Invention and Revision Strategy)

In the same way we use freewriting as an invention strategy, we can experiment

with sketches, graphs, and drawings to help spark ideas and connections between

them. One need not be particularly talented to represent visually an idea one

is beginning to explore. In fact, stick-people sketches, simple geometric designs,

or Venn diagrams can be drawn very quickly by the most artistically untalented

among us and then explained and expanded upon either orally or in writing. These

quick sketches or diagrams are invention tools, much like freewriting. They

can help us see connections, think of metaphors, or help us solve problems in

our drafts or early conceptions of a writing project.

Sketching is a great way to respond to complex readings. Even primitive drawings

or graphs can help people conceptualize complex ideas and contrasting views

before they write about them. Sketching, like freewriting, can also help people

not only generate ideas, but also help them begin to conceptualize how they

might organize, or reorganize, their early or developing drafts.

Here are a few sketches students did in five to ten minutes of class time.

They were working on a 12-page rhetorical analysis, a project that required

them to read a number of suasive texts concerning a controversy of their choosing,

and then to analyze the rhetorical strategies used in those texts. For example,

they were to locate explicitly rhetorical pieces, such as commentaries, editorials,

syndicated columns, etc., representing various positions in a controversy of

their choosing (racial profiling, efficacy of the anthrax vaccine, renovation

of Soldier Field in Chicago, wolves in Yellowstone Park, etc.) And then they

were to examine the rhetorical strategies used by rhetors on different sides

of the controversy. Many students found this project a nightmare. They had to

learn not only to conceptualize the task they were undertaking - how to analyze

the not always obvious rhetorical strategies in the texts they were reading - and

then to organize the rhetorical tour they were taking their readers through.

Since so many students were confused and frustrated by this project, they were

given about ten minutes of class time one day to sketch out the present (or

proposed) organization of their papers. Here are the student sketches and their

explanations.

|

Sketch A - Click on image for larger view.

|

|

Sketch A - This

is "Jessica's" sketch of her draft at about the midpoint of

this rhetorical analysis project. It says, "Diagram of Paper,"

and it is a linked series of flattened circles and squares with labels

such as "summary of rhetorical analysis," and "Smith's

article," and "analysis of Smith's article." Here is what

she said about her sketch:

This sketch

represents my ideal paper, or what I hope my paper looks like when completed.

The "boxes" or rectangles represent the major topics of the

paper and how much emphasis will be placed on them (as shown by size).

Ovals between all paragraph, and the attention-getter "sparks"

around it because it is perhaps the most important part of my paper.

If I want the readers to be interested and read my paper, the first

sentence must stand out. Tied in with the conclusion, the "so what"

question also has "sparks" around it, emphasizing the fact

that this question must be addressed and answered if my paper is to

have a purpose.

|

|

|

Sketch B - Click on image for larger view.

|

Sketch B - This

is "Karen's" sketch of her draft at about midpoint in her

rhetorical analysis project. There is a stick figure with an unhappy

face trying to get her paper over a brick wall of this class project.

Here is what she said about her sketch:

This sketch

shows two sides of me. The me on the left is me now. The me on the

right is hopefully the me very soon. Separating the two me's is a

brick wall which I must overcome. Me-now is not happy with her paper,

while future me is inspired and full of ideas. I must defeat the brick

wall before I can hand in my paper. Hovering over the brick wall is

this class, surrounded by everyone else's papers. This class, their

ideas, and their papers are trying to help me look over the wall and

see my inspiration.

|

Then we talked about these student sketches in class, either via the blackboard,

white board, overhead projector, or the student simply showing around his or

her sketch. Hearing the various approaches and organizational patterns seemed

to help everyone generate possible major revisions in their own work. Hearing

these overviews also provided opportunities to intervene in the revising process:

to discourage long, boring summaries of their controversy, for example, and

to encourage instead the more sophisticated analysis of the rhetoric used in

written arguments concerning the controversy.

Sketched Responses to Readings

A few weeks ago, in a graduate class in Research Methods in Composition Studies,

we were discussing Gregory Clark's and Stephen Doheny-Farina's article, "Public

Discourse and Personal Expression: A Case Study in Theory Building" (Written

Communication 7.4 October 1990, 456-481). It is a complex analysis of a student,

"Anna," who must learn both the discourse conventions in, and quite

different assumptions regarding, writing required in a college literature seminar

and in a local community organization, Responsible Childbirth. As Clark and

Doheny-Farina explain, writing in the literature seminar seemed to value personal

expression and original ideas, while writing at the social agency seemed to

value a "collectivist" approach that furthered the aims of the organization.

At the end of their analysis, Clark and Doheny-Farina invite alternate interpretations

of their analysis.

To start the class discussion of this article, class members were asked to

sketch "Anna's" predicament as described and situated by Clark and

Doheny-Farina. After they completed that visual representation of the authors'

argument, they were then asked to incorporate the first sketch into another

one: Clark's and Doheny-Farina's interpretation of this case study, then contextualized

in the ways those authors invite us to. In other words, how might their interpretation

be situated in a set of assumptions in a way similar to what they describe about

Anna's two writing situations? Here was the instructor's sketch:

|

Dunn's sketch - Click on image for larger view.

|

|

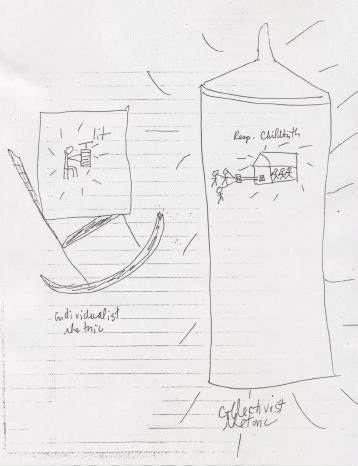

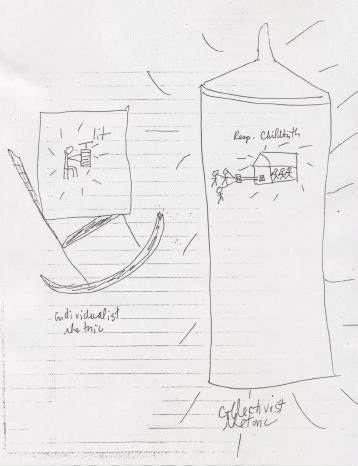

Dunn's Sketch - On the

left is a stick figure (Anna) writing her literature paper. The focus

(light coming off in spokes) is on Anna as an individual and on her text.

On the right, at Responsible Childbirth, is Anna and her colleagues (in

the building, all with pens, all working on the text, which will be read

by different readers outside the agency. The focus (light coming off in

spokes) is not on the text or the writers, but on the agency itself, the

building in the sketch.

Here is the instructor's (Dunn's)

description of her sketch:

After I drew Anna and her

paper on the left and the agency writers and their building on the right,

I contextualized Clark's and Doheny-Farina's analysis. I drew a box

around the "Anna and her text" sketch (with the writers' title

"individualist rhetoric) and placed it in a rocking chair, because

in my view, Clark and Doheny-Farina interpret this view of writer and

text as old-fashioned and outmoded. Around my sketch of Anna at work

(with the writers' title "collectivist rhetoric") I drew a

baby bottle, because in my view, Clark and Doheny-Farina interpret this

view of writer as being the more desirable, current one. I do not claim

to have the last word on how to interpret this article.

|

The instructor's sketch, and the graduate students' sketches of this article - which

were all completely different - was a great way to begin discussion of this article

and of different assumptions about writer, text, and rhetoric. It also led to

a larger discussion of composition research, theory, and practice, a major topic

of this course.