Student Perceptions: Survey Results

Sections: Platforms Used | Yik Yak Specific Responses

To find out more about how students thought about the anonymity practices in social media platforms, I created an online survey which was distributed to composition and technical writing courses at the University of Arkansas.

Survey results are presented to provide information about the research space and as context for the project. After viewing survey results, I was able to better format my interviews to address remaining questions. The survey results, then, provide a larger context to the project while the interviews get into more specific questions about use.

In the larger project, I focused on both ephemeral and anonymous social applications; however, in this webtext, I focus on anonymity as the main characteristic. For that reason, my discussion of survey responses focuses on student responses in the Yik Yak section, a section that 186 users (33% of the total number surveyed) completed.

These survey results begin answering my first research question: why are students using (and why do they stop using) anonymous platforms.

Platforms Used

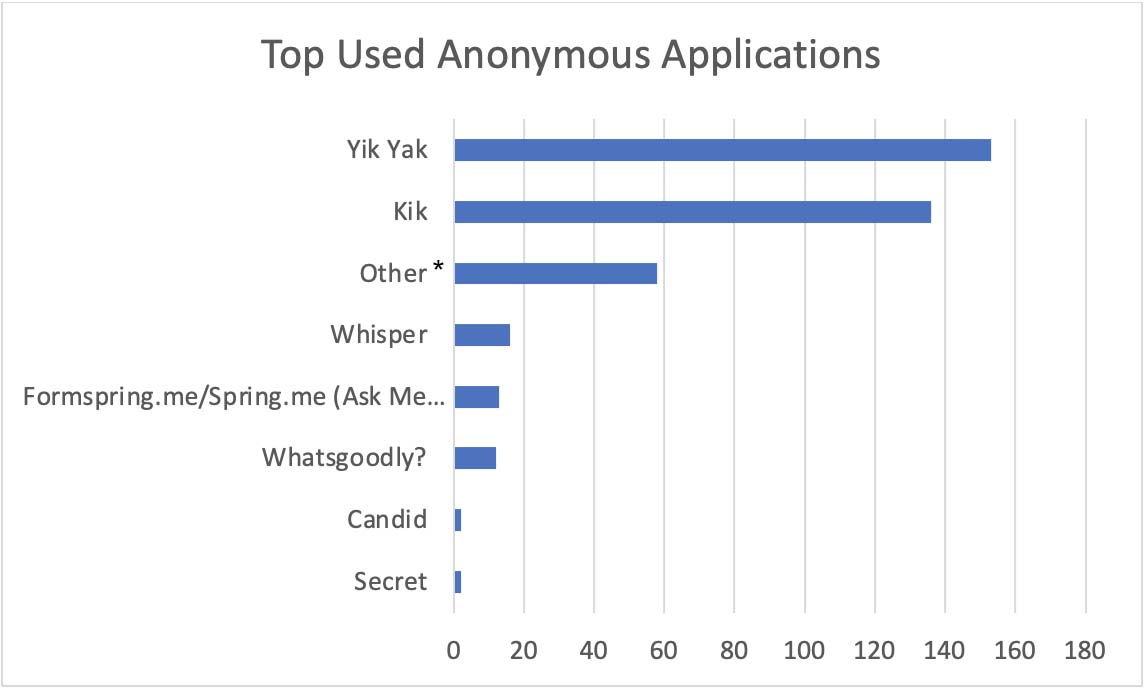

Before designing the survey, I downloaded several applications with anonymity practices, some of which, like Yik Yak, used geolocation to form location-based communities. I monitored the number and regularity of posts on these applications for a two-week period. From my observations, I concluded that the two anonymous applications used most in this local community were Yik Yak and Whisper, an anonymous image and video sharing application similar to PostSecret.

As can be seen in Figure 2, survey results partially supported this conclusion. Survey participants did not report using Whisper in great numbers, though the local Whisper consistently had new posts. It may be possible that students did not feel comfortable admitting their use of Whisper, which, in this area, often consisted of posts asking for relationships or hookups. This discrepancy could also be explained by the fact that the area around campus includes at least one high school, which may account for more of Whisper's userbase.

Reflective Audio: Nonusers?

TRANSCRIPT: Because I knew that not all students would use anonymous and ephemeral applications, I also provided an option on the survey to select a box which read "I have NEVER used anonymous or ephemeral social media (directs to end of survey)." Of the 558 survey participants, 96 students selected this option. However, a closer look at survey results revealed that this number may not necessarily be correct. Of those 96 students, 80 of them indicated that they had used one of the platforms listed on the preceding question. Some participants either misunderstood the question or purposely wanted to be directed to the end of the survey. Thus, the actual number of students surveyed who had never used an anonymous and/or ephemeral application is much lower: 16 of 558 students.

In the future, this issue could be corrected in the survey design process. My intention in putting this option on the same page as the question about platforms was that students would be able to see a list of applications that fit into the anonymous or ephemeral designation before having to select whether or not they had used these. However, because it was so easy to select more than one response, it is possible that participants did not realize what they were doing. In future projects or similar studies, the platforms question should have an option to indicate that the participant has never used one of those platforms. Another section should then be provided, asking a question of whether or not they have ever used an anonymous or ephemeral social media platform with the option selecting of "yes" or "no". The "no" option could then direct to the end of the survey. While this would not prevent accidental selections or purposefully navigating to the end of the survey, it would provide a clearer separation.

Students were asked to indicate which applications they either currently used or had used in the past. In later sections of the survey, users were asked again if they had ever used a certain application. In the case of Yik Yak, however, this number was higher than indicated on the initial platform question. This survey was distributed as Yik Yak was on its initial decline, and later survey results indicated that many former users had stopped using the application by the time they participated in the survey. This discrepancy can most likely be explained by a misunderstanding on the initial question: users may have thought this question asked which platforms they currently use.

The next most often mentioned platform was simply "Other," indicating that there may be some applications used by students that were simply not on my radar. Because the original survey asked students about both anonymous and ephemeral applications, I have no way of knowing if all of these responses were geared toward anonymous applications. However, students did have the option of writing in responses here. While some mentioned applications I had not yet heard of—Afterschool, a high school-based anonymous text app, for example—most mentioned applications such Instagram, Twitter, and Tumblr. While these are not platforms that meet my definitions of anonymous (and/or ephemeral), students may have considered these applications to be anonymous since a chosen username does not have to be associated with a user's actual identity. This survey result continues to bring into question the definition of anonymity, which I have discussed in other sections. In addition, it shows that students may also have some difficulty pinning down a definition of anonymity. The answer might be that it's not always the application itself that is "anonymous" but rather the way the application is used.

The results shown here seem to demonstrate two conclusions, which were backed up in later parts of the survey: Students most often use platforms that involve direct message (Kik) and/or platforms that involve location-based communication to form communities (Yik Yak, Whisper).

Yik Yak Specific Responses

Sections: Common Uses | Leaving Yik Yak | Influences of Anonymity: Harmful Behaviors | Users' Value of Anonymity

In the following section, I take a deeper look into survey responses for the section of the survey that considered participants' use of the anonymous application Yik Yak.

At the time my survey was conducted, the original Yik Yak application was already on the decline. Handles (usernames), which had previously been enforced by the application, had just become optional again, but many users had already abandoned the application for one reason or another. My observations of the local Yik Yak feed confirmed that students were not using the application as much as they had been when I had done my first research project in this space (West, 2016). For this reason, some survey questions were designed to explore why students had previously used the application and why they may have stopped using it.

As I mentioned earlier, the number of students who completed the Yik Yak portion of the survey was slightly higher than those who reported using Yik Yak on the initial platform question. 186 participants (33.3% of the total participants) selected that they had used the application and were then asked to answer further questions about the application.

Common Uses of Yik Yak

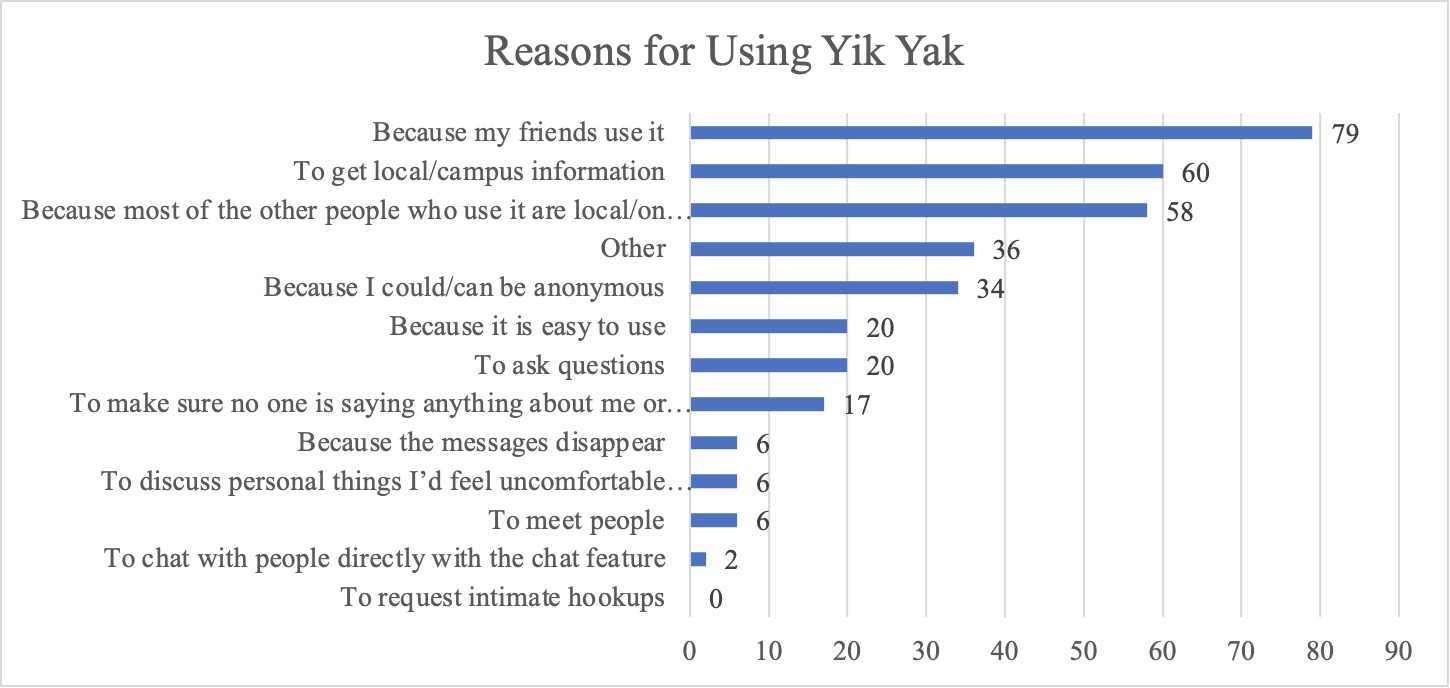

My observations at the time had shown that the local Yik Yak feed was once used frequently by students and other members of the campus and surrounding communities. These users once found value in Yik Yak, so I sought to determine the reasons that participants initially had for using the application. My previous study showed that many posts on the application seemed to serve some purpose in the community. I wondered how participants would characterize their reasons for using the application. Figure 3 shows these responses.

As seen in the figure, participants' top reason to use the application was because their friends used it. Because Yik Yak, for much of its existence, was anonymous and did not provide any feature for friending or following others, I find it interesting that friends still played such a strong role in the adoption of this application. This reason can perhaps be attributed to the other most-mentioned reasons: "to get local/campus information" and "because most of the people who use it are local/on campus."

Many of the reasons for using Yik Yak center on relationships and community, even though the application provided no way of discerning these relationships. Even the direct chat feature does not seem to be used frequently by these participants. This finding, though, seemed consistent with other studies of anonymous applications (Pitcher, 2016; Wang et. al, 2014): the location feature does allow for stronger connections than a wholly anonymous space. Because Yik Yak was geofenced to a certain area, local friends could see the same information. Conversations begun or seen on the local feed, then, could perhaps continue or be commented upon in the physical space.

Thus, the application seemed to be popular because of the connection with the local community rather than specific individuals from the community ("to meet people" and "to request intimate hookups" were also low on the list).

Also worth noting, of course, was the relatively low rank of “Because I could/can be anonymous,” ranked as the fifth most popular reason for using the application. More personal options&such as “to make sure no one is saying anything about me or organizations I belong to” and “to discuss personal things I'd feel uncomfortable sharing in other places;”&were also not mentioned frequently. Again, students may not have felt comfortable sharing this information on the survey, but these aspects come up much more frequently in the interview portion of my project. Ultimately, the community-centrism of the application, not its anonymity practices, seemed to be the major contributing factor in its use.

Leaving Yik Yak

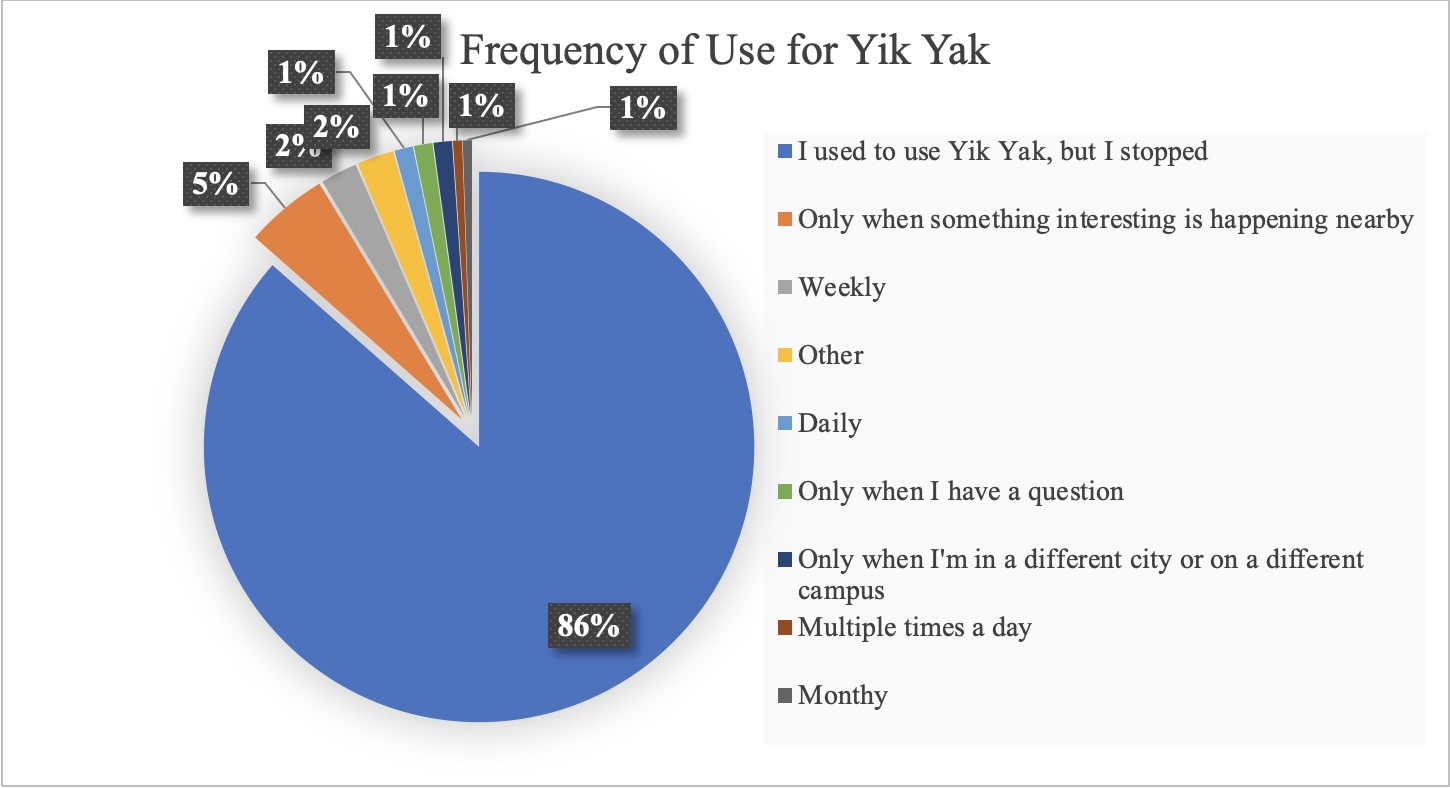

If the community feel was the major contributing factor for using the application, then I would imagine that users have left the application because of some disruption in this community. As I had expected, most survey participants reported that though they had used Yik Yak in the past, they did not currently use Yik Yak. Figure 4 shows the frequency of use for Yik Yak; most participants indicated they no longer log on to the application.

The figure shows that the clear majority of participants (160 respondents, 86%) noted that they no longer used the application at all. This finding was consistent with the timeline of the original Yik Yak's demise (Safronova, 2017). The next most selected item, “Only when something interesting is happening nearby,” indicated that some users still felt led to consult the local Yik Yak community when something in the physical community seemed interesting. Still, this figure demonstrates that the local Yik Yak community had, for the most part, disbanded at the time of the survey.

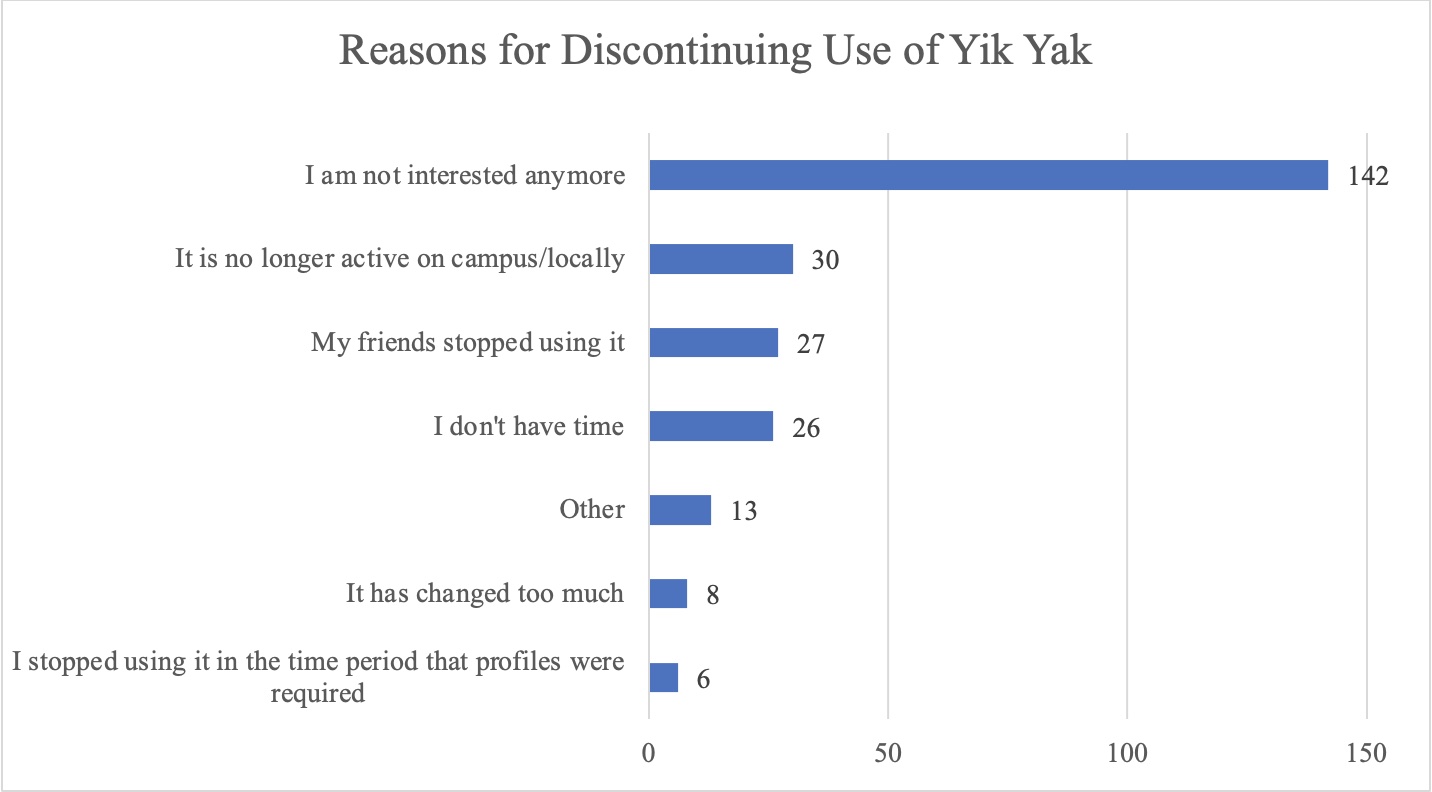

Because I anticipated this type of response, I asked participants why they had stopped using the application; participants were allowed to pick more than one option or write in their own in the other category. Figure 5 provides an illustration of their responses.

Surprisingly, while the reasons for using Yik Yak seemed to focus on the influence of others&emdash;either friends or the community&emdash;the top reason for discontinuing use was personal: lack of interest. I assumed that the decision to leave the application would most likely be fueled by Yik Yak's back-and-forth with handles. However, participants' responses did not support this idea, though it's possible that many factors were involved in their waning interest. In fact, in another question, 68% of participants reported that they stopped using the application before handles became required (and then made optional again).

As it seems much of these participants left Yik Yak before handles became required (and then optional again), it is impossible to tell from this project the influence of handles themselves had upon user engagement with the platform. Luckily, this question was not among my original research questions, but it does offer up the possibility that perhaps contrary to popular opinion, it may not have been the implementation of handles that brought about Yik Yak's fall, something that Montalbano (2021) concluded as well. But it's important to note that this project only shows the thoughts of a specific community.

Influences of Anonymity: Harmful Behaviors

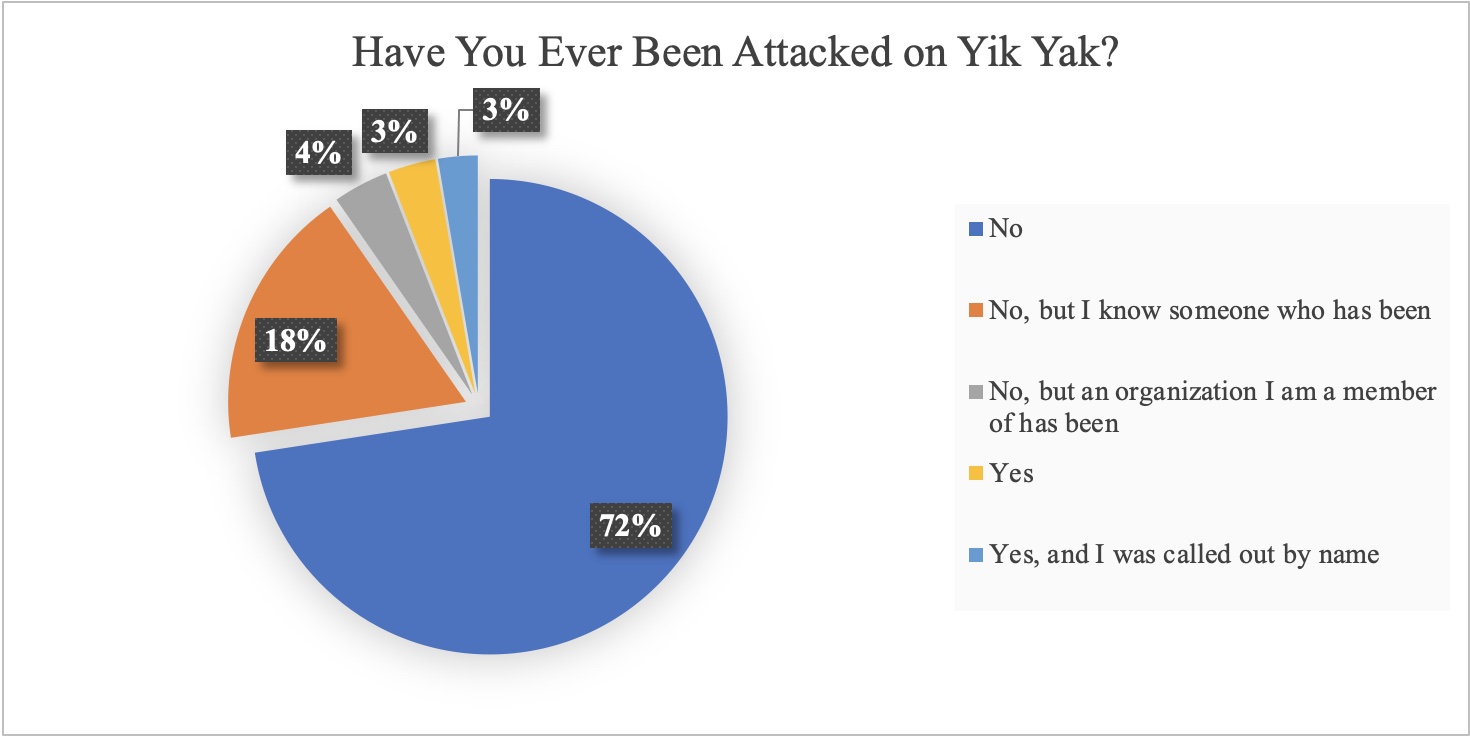

Criticism of Yik Yak, as previously discussed, has centered on its anonymity, especially as far as this feature allows and perhaps encourages bullying and harmful behaviors. If users began to leave the application before handles were implemented, perhaps it was because of the hateful atmosphere that can sometimes develop on Yik Yak's local feeds. I asked users if they had ever felt attacked on Yik Yak; their responses are shown in Figure 6.

Responses indicate that most participants had never felt attacked on the application; however, a fair percentage of responses (28%) mentioned some sort of attack may have happened, whether to them, another person, or a group of people. But because of the number of participants who say they had never experienced a personal attack, it is impossible to attribute the mass exodus from the application in this community to this behavior.

Though this project does not show that a negative environment as a primarily reason for decline (it was also not included in any of the other responses in the reasons for leaving the platform), this does not negate the harm that anonymous applications have in numerous other communities. Based on the demographic responses in this survey, only 32 of the 186 participants for the Yik Yak portion were Black, Indigenous, or People of Color, which accounts for 33% of the total number of BIPOC participants. Ezster Hargittai (2012) pointed out that certain "demographic characteristics and social surroundings" might influence the types of social platforms in which users choose to participate, so it's possible that BIPOC participants were less likely to use Yik Yak in general. While there was a larger population of women who participated in the survey (94 out of 186 participants), 11% of these participants reported having been personally attacked on Yik Yak; only 3% of men reported the same. I echo Li and Literat's (2017) call for further research for “scholars to look at the role of cultural factors in the use of anonymous and hyperlocal platforms, and investigate whether the use of such technologies would differ in other contexts or user groups.”

Users' Value of Anonymity

Because anonymity is central to my research, I wanted to know more about how participants valued this characteristic. Surprisingly, the results of the survey showed that this characteristic did not have a big impact. Figure 3, Reasons for Using Yik Yak, shows that anonymity was ranked 5th as a contributing factor. While still quite high in rank, this characteristic does not overtake any of the features related to geofencing and community.

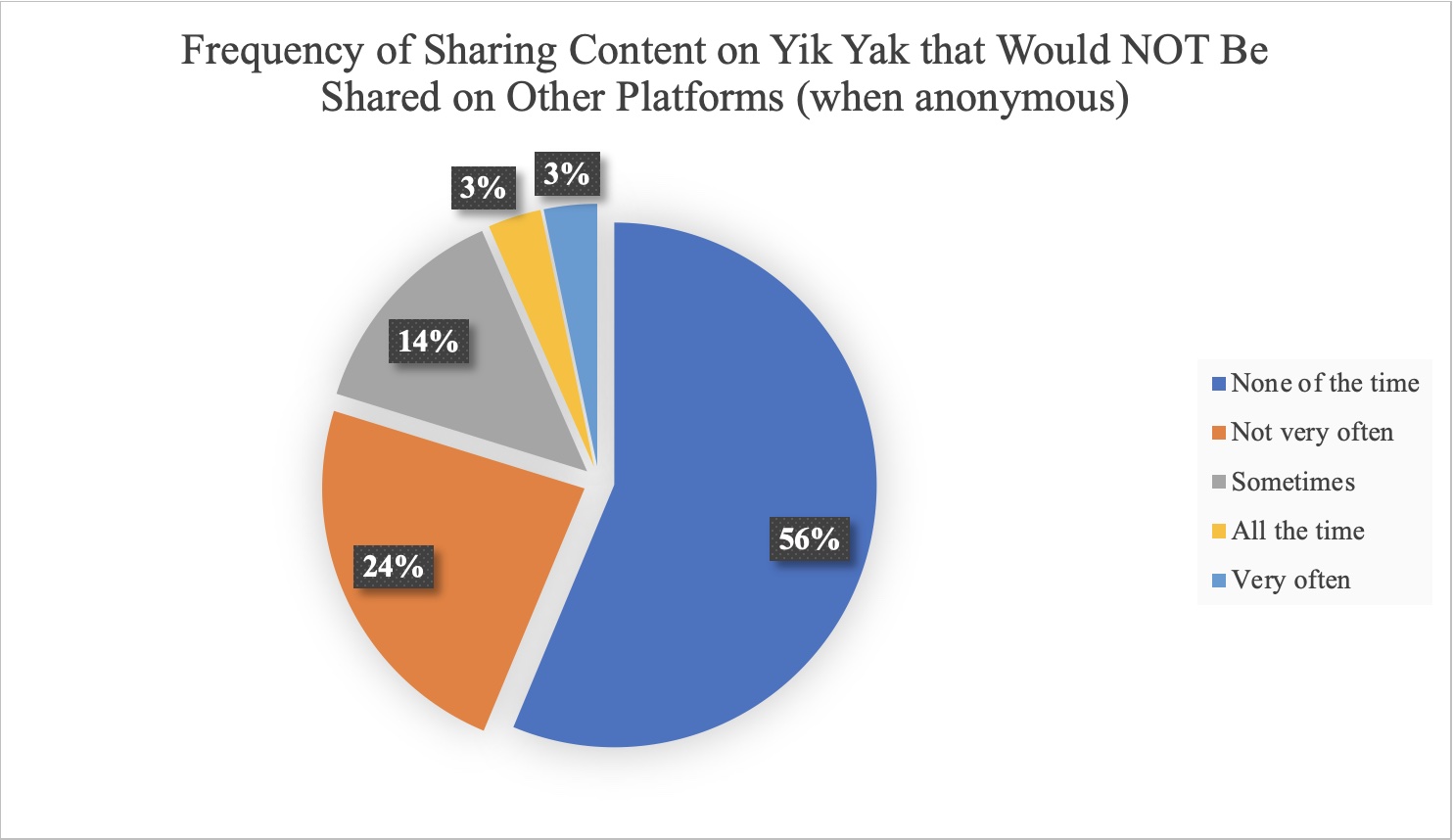

In addition, I asked participants to report how often they would share something anonymously on Yik Yak that they would not share on other social networking sites.

Figure 7 seems to show that participants do not value anonymity as much as I had expected. Indeed, over half of the respondents reported that they never posted content on Yik Yak that they would not post elsewhere. This result seems to imply that participants would say the same things they would say on Yik Yak even on accounts that are tied to their personal information. Participants may have worried they might be outing themselves as trolls, or, again in the short time span of the survey, did not have time to think about their answers fully.

Overall, the survey results indicate how participants use these applications, what features they privilege, and how they compare their use of these applications with more traditional applications. In these results, I saw a clear focus on community, a privileging of who uses the application and if the participant feels they belong to this group (either a friend group or local group). Through the survey, participants seem to identify that the application's community-specific aspects might have been more important in their use than its anonymity practices.