Anonymous Platforms

Sections: Defining Key Terms | Real Name Policies | Introduction to Yik Yak

Anonymity in online spaces is not a new concept, but social media platforms that privilege anonymity as a major characteristic seem to be a relatively new addition to the social landscape. Though these mostly smaller startups have not eclipsed tech giants like Meta and Twitter (currently rebranding to X but referred to as Twitter throughout this webtext), anonymous applications continue to be popular among users. Even Facebook has incorporated anonymous aspects—in 2019, they rolled out anonymous posting for groups that were deemed "health support groups" (Farr, 2019).

In this section, I will define (or in some cases attempt to define) the terms that I'll continue to use throughout this webtext. Then, I will discuss some possible reasons for the proliferation of anonymous applications, and I will explain the primary research space to which I refer throughout this webtext, Yik Yak, a hyperlocal anonymous and ephemeral social media application.

Defining Key Terms

I first want to clarify how the applications that I'm referring to differ from anonymous or semi-anonymous realms like 4Chan and reddit (Shepherd, 2020a; Shepherd, 2020b; Sparby, 2017). To do this, I will break down the major terms that I'll continue to rely on throughout this webtext: platform, application, social media, and anonymity.

Put broadly, a platform is a system that allows groups of people to interact in some way. The reasons for these interactions are many: to buy or sell products or services, to collect data, to socialize, to build communities (Srnicek, 2017). But the meanings of the word platform are even more diverse, as Tartleton Gillespie (2010) noted, ranging from computational and architectural to figurative and political. For my project, though, I rely on the definition of a platform as a digital space for people to interact.

I define application as the delivery service of the platform—the actual software that allows users to access the platform. Applications may be accessed through the web or bought and/or downloaded on mobile devices.

Social media has broad and varied definitions, but some of those definitions actually preclude anonymous applications. An often-cited definition comes from danah boyd and Nicole Ellison (2008): "We define social network sites as web-based services that allow individuals to (1) construct a public or semi-public profile within a bounded system, (2) articulate a list of other users with whom they share a connection, and (3) view and traverse their list of connections and those made by others within the system" (p. 211). This definition works well to define many platforms, particularly popular ones like Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. But it is difficult to fit anonymous applications within this definition, as they don't often rely on profiles, and connections are difficult to establish or determine.

For the purposes of this project, I choose to use a broader definition of social media platforms, one that can encompass anonymous applications as well: Liza Potts's (2014) definition of social media systems as "the actual systems that allow people to form, join, and participate in networks" (p. 6). Potts's definition does not preclude any system based on its core characteristics: if users are present and participating, a system meets this definition.

Like social media, anonymity is a difficult term to pin down. As Emily van der Nagel and Jordan Frith (2015) argued, previous definitions of anonymity use the idea of an "anonymity continuum," which allows people to think beyond just categorizing applications as either "anonymous" or "not anonymous" (Donath, 1990). While van der Nagel and Frith acknowledged that the continuum is a helpful starting point, noting that the continuum becomes a problem when "a flat line between binary opposites is assumed to account for all the nuances within anonymity practices." They argued that their discussion of anonymity moves past the continuum and "into thinking about anonymity practices, which include pseudonyms (Lewis Carroll and John Le Carre), mononyms (Madonna), stage names (Buck Angel), anglicized names ('Michael' instead of the Slavic 'Mykhailo'), usernames or handles that either play on a given name (grassisleena) or avoid mentioning a given name at all (labcoatman), and the interplay between these malleable identities."

Reflective Audio: Defining Anonymity

TRANSCRIPT: I wish I was able to say that in this webtext, I am going to provide readers with the definitive discussion of what it means to be anonymous on social media applications. But the truth is that we're still learning about and exploring these applications, and our definitions may very well differ from the definitions of other users and/or researchers. In fact, I'll talk about the differences of definitions more in the interviews and implications sections. Is it bad that we don't have a go-to definition for anonymity? Or is it fitting that the idea of anonymity is itself a bit anonymous? Because social media platforms and policies are continually changing, it's unlikely we'll come to a succinct and definitive definition of anonymity. What is important, though, particularly for people who are writing about these platforms, is to establish some sort of definition through which readers, whether they agree with the definition or not, can understand the terminology in context.

Similarly, in this webtext, I refer to different types of anonymity practices that, taken together, can give us a better understanding of the complexities of defining an "anonymous" platform. As van der Nagel and Frith went on to say, "both anonymity and pseudonymity allow people to enact specific, and arguably valuable, identity practices online." So ultimately, anonymity is not the complete lack of identity. Some platforms, like Facebook, require that users share their real names and photos of themselves (Facebook, "What names are allowed?"). And platforms like Twitter and reddit, which do not require real names, allow for different anonymity practices, giving users a choice of having usernames/handles that are associated with their names or not. I trace the early origins of online anonymous platforms back to MOOs and MUDs, which certainly enacted many different anonymity practices.

Yik Yak, a hyperlocal anonymous and ephemeral social media application that serves as a major touchstone for my research into anonymous applications (discussed in more detail in later on this page), originally did not require or even allow a real name/photo or a username. However, information like the users' phone numbers were required when signing up for that application, though this was not shared with other users. Because anonymity online can be a very complex idea, I describe Yik Yak's early anonymity practices by using Graeme Horsman's (2016) idea of approved anonymity. Approved anonymity describes applications that do not provide any user identification to other users, though the service providers themselves do hold some identifying data. This type of anonymity is most prevalent in social media and messaging applications like those I study: The technology companies that develop and distribute these applications have access to some identifying information, but users—and researchers like myself—do not.

"Real Name" Policies & Reasons for Anonymity

While profile-based platforms like Meta (Facebook and Instagram) are still giants in the field, other platforms that don't ask users to establish profiles or use real names have become increasingly popular. Perhaps this is in direct response to some profile-based platforms' insistence on users going by their real names—or, as Facebook has articulated, the name that "appear[s] on an ID or document from our ID list," which includes birth certificate, driver's license, passport, voter ID, tax ID cards, and other standard identification documents (Facebook, "What names are allowed?"). Should a user lose access to their account for some reason, they'd need to show Facebook one of the approved identification documents to regain access.

The stated reason for establishing these "real name" policies is to provide some sort of accountability, but as danah boyd (2012) stated, there's a lack of data to support that this is the case. More likely, using real names allows platforms to compile more data about their users. boyd argued that platforms are exerting control over users by requiring real names, and there are many reasons that a person may not want to use the name on their identification documents. For that reason, some sorts of anonymity practices should be allowed in online environments just as they are in physical environments, where you can generally choose whether to reveal your name. As boyd noted, "you don't guarantee safety by stopping people from using pseudonyms, but you do undermine people's safety by doing so."

Creators of the anonymous application Yik Yak (discussed further in the next section) stated that their reason for creating an anonymous application was to ensure that everyone's content was on an equal playing field: "That means that everyone's content is treated the same way, no matter who you are. The bad is that many people associate anonymity with bad behavior. It seems as though anonymous networks are sort of under the magnifying glass, but that's to be expected when you're in a new and growing space" (Buffington and Droll qtd. in Hines, 2015).

But anonymity practices do not completely erase identity and experience in a way that always promotes an "equal playing field." As Beth Kolko, Lisa Nakamura, and Gilbert B. Rodman (2020) noted in their introduction to Race in Cyberspace:

You may be able to go online and not have anyone know your race or gender—you may even be able to take cyberspace's potential for anonymity a step further and masquerade as a race or gender that doesn't reflect the real, offline you—but neither the invisibility nor mutability of online identity make it possible for you to escape your "real world" identity completely. Consequently, race matters in cyberspace precisely because all of us who spend time online are already shaped by the ways in which race matters offline, and we can't help but bring our own knowledge, experiences, and values with us when we log on. (pp. 4–5)

Perhaps this is why anonymous spaces like Yik Yak continue to be plagued by "bad behavior"; though the creators claim they can establish some sort of egalitarian space through anonymity, they don't acknowledge the ways that offline behaviors and biases continue to shape those online. (Also, consider the experience of reading this blockquote's introductory statement with author's names removed but the title of the book remaining: for some of you, the authors remained anonymous, but for others, you might have used your own knowledge and experience with that collection to, in a sense, de-anonymize the authors.)

So I am looking to do exactly what the Yik Yak creators imagined I'd want to do—put these anonymous apps under a magnifying glass. My project emphasizes users' reactions to platforms' anonymity practices and focuses primarily on why users do use these platforms rather than the myriad negative reasons they might not want to. To emphasize these anonymity practices to my participants, I used a popular application at the time, Yik Yak.

A Brief Introduction to Yik Yak

Yik Yak launched in the fall of 2013 and drew in users quickly, especially students on college campus and residents of major urban areas. The application allowed users to form, join, and participate in networks based on their physical location, within a 1.5–10-mile radius.

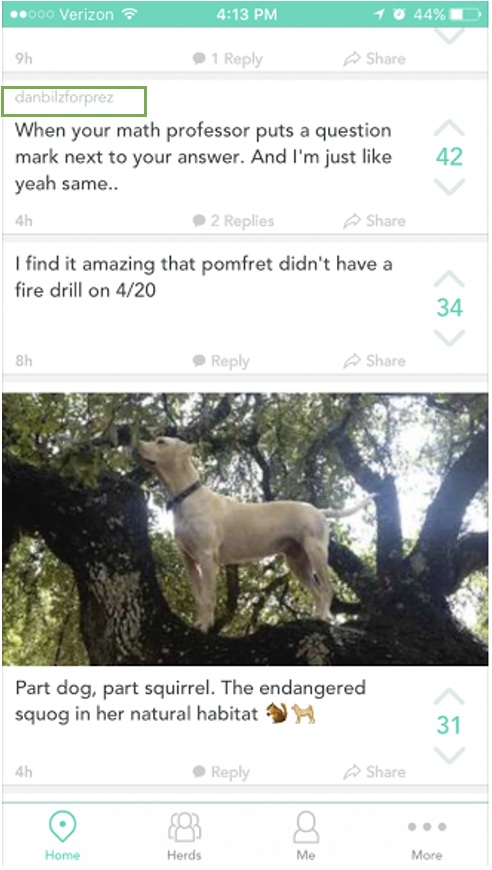

In these local feeds, users could communicate with each other by creating posts, commenting on others' posts, and voting on posts. Through the voting system, posts that received many "upvotes" (i.e., positive ratings) could often be found on a separate "hot" list, while posts that received many "downvotes" (i.e., negative ratings) were dropped from the community feed. Only the most recent 100 posts (those which had not received a certain number of downvotes) were shown on a local feed, and posts were not otherwise archived.

In early 2015, just over a year from its initial launch, Yik Yak had an estimated 3.6 million monthly active users representing over 1,500 college campuses (Smith, 2015). As the application's popularity grew, so did the controversies associated with it, namely occurrences of racist, sexist, homophobic, and hostile posts (see Koenig, 2014; Mahler, 2015; Ross, 2015; Schmidt, 2015). The generally agreed-upon consensus was that, despite the creators' hopes, the application's anonymity lent itself to this behavior, giving users an outlet for these thoughts, presumably without repercussions.

Despite this controversy, however, Yik Yak remained a popular application until the company made several platform-changing decisions, including their decision to create mandatory user handles (or usernames). Though originally presented to users as optional, the application made handles mandatory in August 2016. This change was met with a great deal of backlash from users, and though it was reversed just three months later, the application could never recover. Its user base had diminished so much that the application shut down in April 2017.

Many other applications have sought to capitalize on its former —and other long-standing applications captured some of the fleeing userbase. Shortly after Yik Yak's demise, both Sarahah and Jodel grew in the U.S. since these apps functioned in almost the same way that Yik Yak did, providing locally situated anonymous conversation boards for users. Sarahah was later removed from the Apple and GooglePlay stores in 2018 (Cassin, 2018) after users, particularly minors, faced bullying on the application. Another application, Chatous, allowed anonymous chats situated around particular topics and interests. Other applications, such as Omegle, which has been around since 2009, provided randomized one-on-one chats with strangers. Whisper, an application that allowed users to post anonymous image and video messages, had 250 million monthly users in 187 countries in 2017 (Shieber, 2017). Still other applications, like Honest and TalkLife, attempted to provide anonymous advice and support. I could name and attempt to categorize anonymous applications for the rest of this article, but the point is this: anonymous applications are here to stay.

And this fact was no more evident than in late Summer 2021 when, just weeks after I submitted the first version of this webtext, I received an email from my Google Alert on "Yik Yak." Since Yik Yak had closed in late 2017, most of the emails I received from this alert were OpEds and articles that referenced Yik Yak in a long string of other anonymous applications. But instead of a single article showing up on this alert, there were nine, all with some variation of "Yik Yak is Back" in the title. Suddenly my webtext no longer used research from a dead application; it used research from Yik Yak version 1.0.

The relaunched version of Yik Yak has acquired new owners who have professed to have a stronger stance against bullying and hate speech. Their website claimed that the application is "the same Yik Yak experience millions knew and loved" (West, 2016). The application is not yet as popular as its predecessor, as it currently supports around 2 million users (Woollacott, 2022). Already, though, the relaunched application has been met with controversy. In addition to reports of bullying (Vail, 2022), the application took a big hit in April 2022 when computer science student David Teather used a free, open-source tool to analyze the Yik Yak data and discovered that each Yik Yak post contained a unique user ID code and an exact GPS location. Yik Yak was made aware of the problem and produced updates with bug fixes. Teather noted that some issues still remain because the information is still accessible through previous app versions (Franceschi-Bicchierai, 2022).

What will it mean that Yik Yak has, yet again, undermined their core characteristic of anonymity? At the time of writing this webtext, the repercussions are unknown. The userbase of the relaunched version of the application is still small enough that the aforementioned issues didn't make quite the waves as the many controversies associated with the original application. But whether this breach of Yik Yak's professed anonymity practices will stifle what might have been a growing userbase, we may never find out. In mid-2023, Yik Yak's new owners made a decision to further limit the userbase: Now only users with official college email addresses can sign up for and use the application. The owners tout this as an added safety measure. Anonymity remains (on the public interface), but gone is the geolocated radius that once defined the application.

Yik Yak serves as a big part of my research project. My interest in this application is really what began the whole process. The application truly rose, fell, and rose again during the span of this project. Yik Yak's initial decline was interesting for several reasons: it provided a case study of what happens when applications change their fundamental characteristics; it showed the influence of critical mass media on new social media startups; and, especially interesting for this project, it provided me a chance to ask users about the controversial handle policy that the application implemented. I hope to someday have much to say about the relaunched version, but that will have to wait for another opportunity: such is the plight (and the delight) of an online researcher (discussed more throughout this webtext).

Reflective Audio: My Relationship with Yik Yak

TRANSCRIPT: I downloaded the Yik Yak application after hearing about it from a colleague, and I approached this space as a research space, even before I became a user of this space. I observed users on the application long before I posted my own content, and I kept up with media coverage as Yik Yak grew. This is important to acknowledge because I position myself in this project, and in the previous project from which this project grew, as a user. But I have always been a researcher-user, and thus the ideas that I bring to these spaces are automatically focused on that research. The ways in which I see student-users navigating the platform are filtered through the interest I have in the platform as a research space.

It is for this reason that critical research practices work so well for this project. In my previous project, I categorized Yik Yak posts based on student-users' rhetorical moves on the platform. I did so not as a user of that space, but as a researcher, but it has taken me some reflection to be able to understand that. In the current project, I wanted to have a better idea of why and how student-users are navigating these spaces, and to find that out, I needed to go directly to these users. While the discussions and implications for my research are still filtered through my privileged position as researcher, the data comes directly from student-users. I know I cannot erase my privileged positioning, but I can enrich the project by asking users to participate.