Check here for more information on the homepage rugs.

Nancy Small with Riyaz Bhat

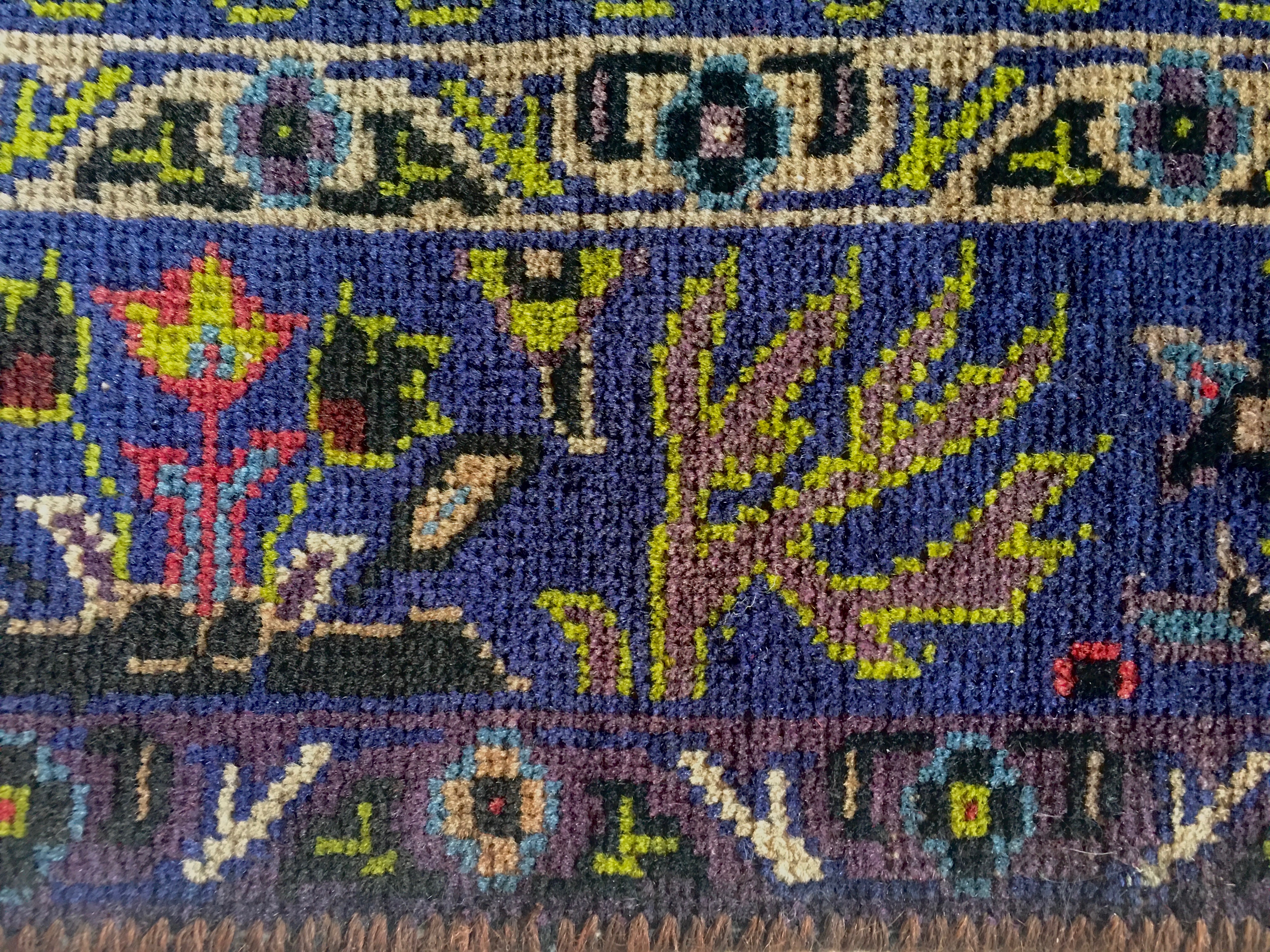

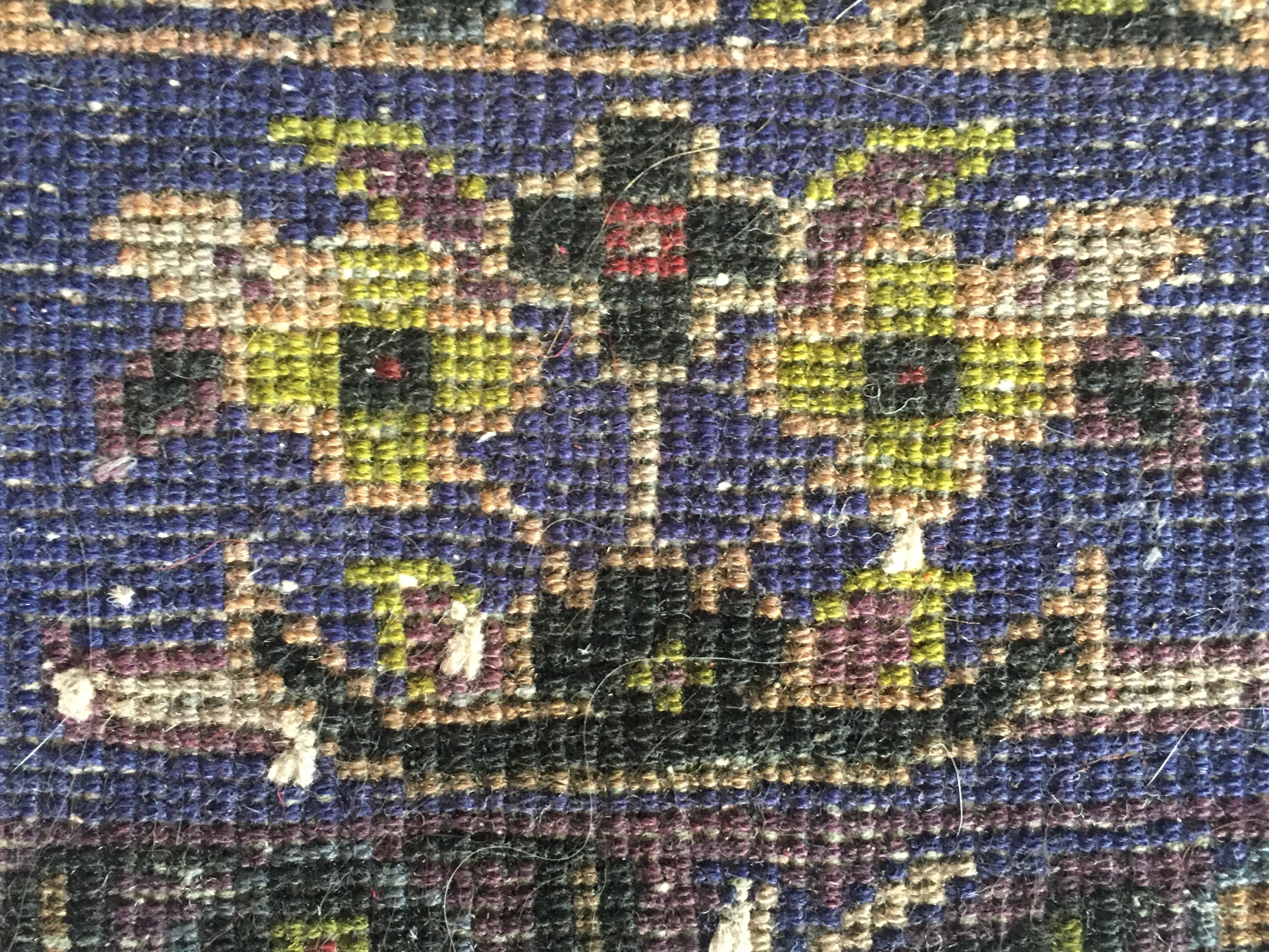

Although permeated with a rich history and cultural context of their own, tribal rugs primarily inspire attention in regards to their production techniques and commodified value. Focus on market value constrains the symbolic meaning—creates limiting "selvage" edges—of the rug and shifts the story away from the weaver and the contextualized location of their work. Rugs are evaluated as technical assemblies or specific styles of knotting, types of wool and dye, as well as symbolic features and design motifs as relevant to market value (Forementon, 1972; Housego, 1996; Spooner, 2011; Stone, 2004, 2013; Tzareva, 1984). They occasionally appear as minor characters in stories of factories, bazaars, and war-infested trade routes (Kremmer, 2002; Murphy, 2005). Interweaving the rugs with histories of the regions in which they are produced, some books include limited information on tribal life before digging deeply into design motifs and construction (e.g., Denny, 2014; Opie, 1992).

In his comprehensive study, Parsons (2016) devoted two early chapters to carpet making—both workshop and tribal home-woven—and to nomadic life and furnishings. He committed six paragraphs to describing the harsh life of the family shepherd, a young boy or very old man designated to watch flocks that they may or may not own, including the shepherd's bond with his kuchi dog, the precious "brackish water" for drinking, the "blistering heat," and the "sun-dried lumps of soured milk, called grut, which is his main food" (Parsons, 2016, pp. 150–151). In contrast, Parsons's limited reference to the roles of women mostly related to a young woman's dowry as a collection of hand-produced items: "Wealth implied a greater number of posessions, while status determined the number of [handwoven] bags which a girl would bring in her dowry" (Parsons, 2016, pp. 32–33). In other words, the commodified value of the rugs were bound up with the value of the brides.

Expansive and beautifully illustrated coffee table books catalog tribal rugs as prized possessions and historical gems. For example, Abraham Levi Moheban's (2016) two-volume encyclopedia offered over 600 entries, 860 color photographs, maps, diagrams, and a conversion of the Gregorian calendar to the Islamic calendar. He comprehensively attended to 25 centuries of artisanal carpet history spread across "places (countries, regions, cities, towns, villages), empires, tribal and nomadic groups, workshops, individual artists, and even patrons," and he spent the heavy volumes documenting specific designs and highly prized particular specimen, describing them by "location, history, production era, techniques and materials, designs implemented, coloration, size range, quality grade, market demand, art and beauty, [and] price and market value" (vol. 1, p. 7). In his preface, Moheban reflected over his compendium and posed the rhetorical question, "what, then, is excluded?" (vol. 1, p. 8). In answer, he noted that contemporary abstract rug designs are outside his scope. What is also missing, even amidst the entries for master weavers and their workshops? Tribal women weavers are missing. None are referenced by name, by family, by tribe, or even as anonymous artisans of highly valued samples.

One exception to this narrative of commodification is Walter B. Denny's (2014) How to Read Islamic Carpets, an art history book which took as its primary focus the relation of tribal rugs to local life. For Denny, rug design is "intimately related to the distinct techniques they exhibit, which in turn reflect the very different environments in which they were produced," and considering these interconnections increases appreciation of the rugs as artistic creations (p. 28). He also used the verb "reading" to describe his close examination of a material artifacts design, a systematic consideration of technique and modality as they reveal "a great deal about the weaver's process as she confronted both the limits and potential of her medium, improvising a corner here, adjusting the height of a [design feature] there" (p. 14). Denny began to focus on the weaver by noticing "clues into the weaver–designer's creative process" in the construction of a Turkoman rug (p. 35) but remained relatively narrowed in on the weaver as situated only in her craft. While this remarkable representation of the weaver contrasts her treatment in other tribal rug texts, Denny persisted in muting or erasing the woman-as-agent via generic nouns ("weaver," "dyer"), passive voice, focus on process ("indigo provides blue hues") or product ("the rug features a geometric motif"). When the woman weaving is present, her actions are attributed to repetitive, mechanical processes such as knot tying and yarn trimming. Although Denny acknowledged that "the weaving of carpets has long been a major aspect of women's contribution to the prosperity of a nomadic family or a village household" (p. 31), the goal of his project is art appreciation via attention to disembodied technique. Extending and in contrast to his work, I propose that reading a rug as material rhetoric might take us further: to appreciation of the women weaver's lives and talents in fuller and more complex terms of complex literacies and agency.

Working in terrible harmony with rug commodification, time and space separate us from the women weavers at work in Central Asia. Nomadic and semi-nomadic lives, ongoing violence and political tensions barring travel, and a host of challenges for bridging sociocultural and linguistic differences conspire to make listening directly to them particularly fraught and difficult. The next section introduces an expert in Central Asian tribal textiles who has spent decades interacting with tribal representatives, learning first-hand about the technical aspects as well as the matriarchal process of weaving. Riyaz Bhat is both an ambassador and an educator, linking people of diverse cultural backgrounds and advocating for the expertise of traditional tribal women's work.