Check here for more information on the homepage rugs.

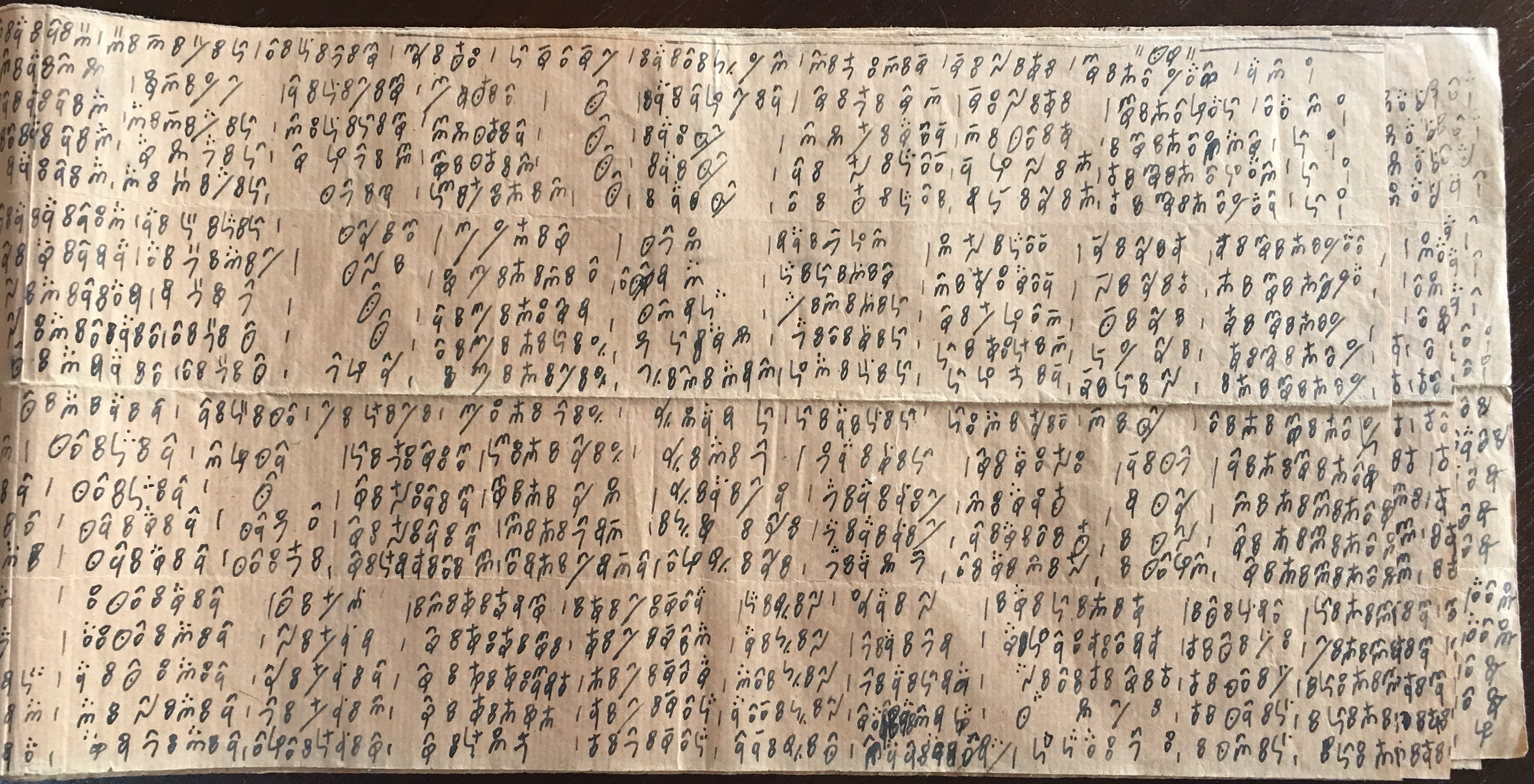

Nancy Small with Riyaz Bhat

My collaborator, Riyaz Bhat, is a well regarded and internationally recognized expert on tribal life and crafts, and his contribution to this webtext is central and substantive. Originally from Kashmir, he is the son of a master designer of fine silk carpets and grew up amidst the looms and intricate pattern charts of his father's workshop in Srinigar. Although his father hoped he would step into that family business, Riyaz's relentless curiosity instead turned to his uncle's trade in handmade tribal carpets. After studying intensely with his uncle for two years, Riyaz took his first trip in 1988 to learn more about tribal life and craft in the northern region of Afghanistan, a dangerous excursion involving armed guards due to the Soviet–Afghan war. Despite that risk and from that point onward, his focus was set firmly on learning all he could about those tribal peoples and their weaving expertise. As he pursued this knowledge and established a career, however, staying in Kashmir and being mentored by his uncle became impossible. Due in part to ongoing political tensions that still plague the Kashmiri–Pakistani–Indian relationship, Riyaz left his homeland and moved to Qatar to pursue a lifelong commitment to the tribal rug tradition and trade.

Riyaz has lived in Qatar's capital city, Doha, since 2000 and has established a reputation not only for importing fine rugs and textiles from Central Asia but also for his deep expertise in and appreciation of tribal life. More than 30 years into his study and career, his knowledge has been built over the course of dozens of trips into Afghanistan and hundreds of interactions with the tribal groups with whom he barters. Back in Doha, he is fondly called The Rug Man, and he has been recognized by being featured on CNN Travel (Neild, 2018a, 2018b), Kashmir Times (Azmat, 2016), The Telegraph (Rutt, 2015), Al Jazeera (Mater, 2015), visitor guides such as Time Out Doha (Time Out Doha Staff, 2016), and innumerable blogs. A visit to his shop on Al Mergab street invariably includes teachings on the people, climate, culture, and process that produce the woolen and silk carpets lining the tiny second story of his shop. Rather than view these works as mere merchandise, he presents them as artifacts of a living culture worthy of recognition and respect, even as it is slowly disappearing as nomadic peoples either choose or are forced to settle in urban spaces as a means of survival.

In the six years (2010–2016) I lived in Doha, my family and I visited with Riyaz on multiple occasions and counted him and and his family as dear friends. Beyond our friendship, however, I have been privileged to sit with him for lessons on tribal life, his harrowing travels into war-torn Afghanistan, and the rug trade, as well as rug design and construction. From our first conversation, Riyaz impressed me with his particular respect for women's contributions in nomadic society. He does not fetishize or romanticize them but speaks of their realities in detail and with pragmatic admiration. He has been motivated by his esteem for these women who cannot read or write, yet begin with natural materials from their surrounding environment (wool from their family's sheep and plants from the land) to expertly produce incredibly complex carpets in both geometric and freehand designs (see Azmat, 2016).

Listening to Riyaz deftly explain the nuances of a particular rug's composition and point out the small variations of color and pattern that mark it as the unique endeavor of a singular artist, I was inspired to learn more about the women who created these works of art. Knowing that I would soon repatriate back to the United States and that I would lose easy access to my friendly expert, I began to imagine a means of reading the rugs we had purchased as a memoir of those women who designed and created them. I wanted a practice to help me maintain these complex connections. To assist me in developing this reading process, Riyaz generously agreed to participate in a formal interview, which took place in October 2015 and lasted a little over an hour. I asked him questions about tribal life, particularly his observations of women's roles and the traditions of carpet design and creation, as well as about aspects of several sample carpets. I reviewed my proposed system of reading a carpet as a memoir text and requested his feedback on my ideas and on a late draft of this webtext. Through this interview and our subsequent correspondence, Riyaz served as an invaluable source of knowledge, particularly because very little is written about contemporary nomadic women's lives.

The next section, Lives & Tools, is informed by Riyaz's teachings and complemented by additional external sources. As preparation for re-reading the the Shirin rug, it provides important contexts about the craft of weaving within tribal spaces.