Filling In the Gaps:

Primary Voices of Japanese American Incarceration

The Rohwer Soundscape: A Walking Tour with George Takei

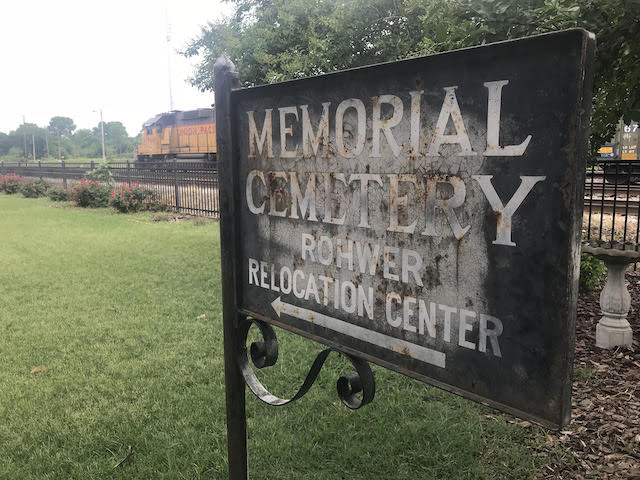

Both times I drove to the Rohwer Memorial Cemetery, in 2014 and 2018, I thought I was lost. The terrain was not unfamiliar to me, having driven through many roads in the rural south, but the idea that a Japanese American memorial cemetery was to be found along an empty two lane highway surrounded by fields seemed out of place, at odds with what I had come to associate with that environment. Unless you are looking for the Rohwer Memorial Cemetery, you are unlikely to come upon it. With the exception of perhaps Manzanar in California, all the physical incarceration sites face this challenge of reaching uninterested members of the general public. The sites are not located in places one would merely stumble upon on a trip, since they were strategically placed on unused land away from highly populated areas.

The Rohwer Memorial Cemetery is all that remains of the original Rohwer concentration camp. Like other sites of incarceration, Rohwer was dismantled after the war. When I drove across the country visiting these sites in 2014, Rohwer was first on my trip, and the emptiness of the space continued to haunt me. While other sites were seemingly abandoned or forgotten, the Rohwer site had been actively ploughed over. With the exception of Poston, Arizona, the other sites I visited had vestiges of the camps; they sat mostly empty, but empty shells of the experience remained. Visitors have the option to walk the land and see the former roads: in Manzanar, stone steps; in Minidoka, a chimney; in Tule Lake, a prison. The inside has been removed, but the shell exists to be filled with new attempts to reconstruct these spaces. Manzanar, for example, has built two barrack facsimiles.

In Rohwer, however, while there is a "walking tour," visitors cannot follow the paths of former roads. The fields are now ploughed over as farmland, and the cemetery sits isolated, the resting place of Japanese Americans who died during their Arkansas incarceration. It's likely that barracks still exist, but my own experience driving around the rural South tells me this sort of uninvited exploration on private land is not advisable for an individual.

A World War II Japanese American Internment Museum exists in McGehee, Arkansas, but I am limiting my focus to the physical site, which acts as a memorial, "a free-standing object within a given geographical space," which can, as Carolyn Handa (2014) claimed, "communicate rhetorically just as much as a museum does" (p. 160). Handa went on to suggest that the memorial's website is also an important contributor to the rhetoric of the space, particularly for "memorials with contested histories" where "a fused rhetorical analysis accounting for both the physical space plus the text and images within its related online space is especially important" (p. 160). In her work, Handa described how the Japanese American National Museum and the Civil Rights Institute in Birmingham, Alabama, make a rhetorical argument to "those who move through their online sites as well as their physical spaces" (p. 157). The Rohwer Memorial Cemetery also makes a rhetorical argument, on the accompanying websites (the website for the museum the National Parks Service website) and through these audio kiosks at the physical site. I find the inclusion of voice through the use of audio kiosks at the physical site to be a critical part of memorializing this space.

In this case, vocal rhetoric not only helps audiences fill in the emotional gaps of the story, but also the physical ones. While the structures themselves may not be rebuilt or recovered, the memory, the voice of George Takei, asks the visitor to rebuild the site, to look over the empty land and imagine the life of Japanese Americans who lived there. In this way, the audience becomes an active participant in the public memory of this event, as our own imaginations must help to rebuild these structures.

As you enter the Rohwer Memorial Cemetery, a facsimile of a guard tower sits upon a gravel and dirt road. The first audio kiosk is located here, with the rest located further along. On the left of the road sits the Memorial Cemetery, with the remainder of the audio kiosks to the right. These kiosks act as a kind of mediated voice, a "voice that extends beyond its body of origin" thereby becoming "more immediately accessible, expanding our abilities not only to speak in voice, but also to compose with voice as a malleable material" (Anderson, 2014). Because the voice of George Takei is a culturally privileged one, most viewers would recognize it without prompt. Eight recordings exist, some of which are housed in the same kiosk. For my purposes in this webtext, I've included the video of the final kiosk to provide an example of the soundscape. The voice rings out over the silent ground, and light gravel crunches and wind can be heard in the clip.

What this video cannot capture is the heat, though it's worth noting that a May afternoon cannot compare to the humidity of August or September. The small breeze was welcome, as we were tired from driving and visiting the museum. Both times I visited this kiosk, in 2014 and 2018, I became emotional, swallowing back a choked-up feeling. The eeriness of the voice across the empty land creates a feeling that I have trouble describing—the voice feels… lost, perhaps, floating forever on this land with the many memories that were made there.

I feel an almost ghostly experience listening to these audio files on the abandoned land. As a mediated voice, Takei becomes this other-worldly tour guide whose voice finds no corporeal body. While I have been privileged to visit many sites of incarceration, I have found the inclusion of voice on the physical land to be the most compelling of all my experiences visiting museums and memorials. I recognize, of course, that I am perhaps biased—that I experience a relationship to the southern rural land that everyone may not, but I also believe the vocal rhetoric plays a significant role in my emotional investment in the land. This ghostly feeling is compounded by the visit to the cemetery, the only structure remaining, a reminder that many Japanese and Japanese Americans did not ever leave camp. Some graves belong to infants, which makes me want to research the mortality rate in births at these camps. These feelings are guided by Takei's voice, as he walks the audience through various aspects of the incarceration experience.

Takei combines the qualities of the voices from the Core Story section, in that he reads a script and so lacks the spontaneous speech acts associated with conversation (e.g., "uh," "um," laughter, long pauses), but as a person who experienced incarceration and as a master storyteller, Takei makes use of short pauses and elongated words to add emphasis.

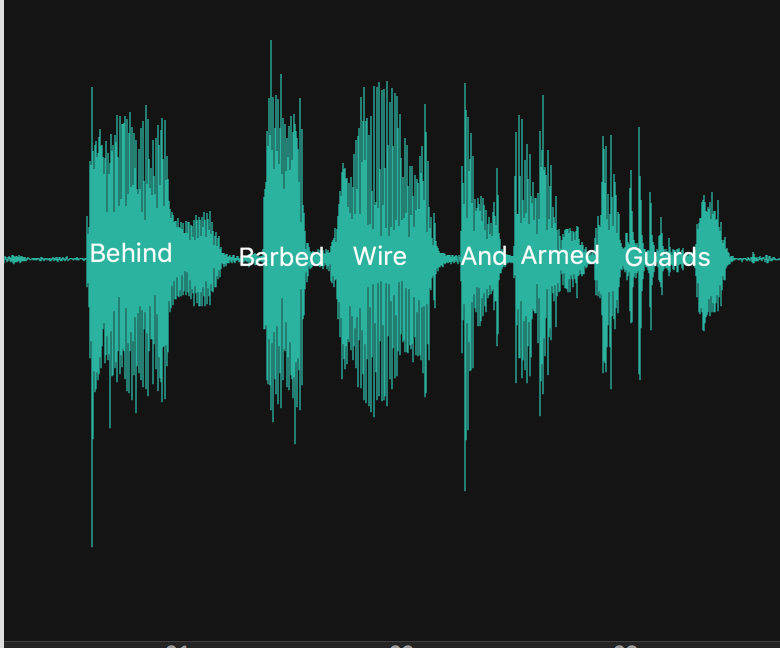

The following provides a visual representation of the beginning of his story:

Unlike Eisenhower, whose descriptions felt clipped, Takei draws out certain phrases, such as "behind barbed wire and armed guards," a point in the narrative which marks a clear slowing down.

Slowing down such a phrase places emphasis on the act of incarceration; the barbed wire as the physical fence between the outside world, and the armed guards as the violent representation of that incarceration. The fence itself is an important object for many narratives, as is evidenced in Helen Herano Christ's remembrance with the snake in American Concentration Camps (Densho, 2015).

Opening the kiosk with the directive to look "on the other side of the gravel road" is a particularly compelling moment that frames the rest of the audience's experience with the narrative. We are called away from looking at the kiosk to look at an empty field. Through this small directive, Takei encourages the audience to experience the multisensory nature of the spatial rhetoric. The emptiness, what is not there, creates, I think, a stronger emotional reaction than any attempt to rebuild could. The rebuilding can only be a facsimile, a synthetic version; the emptiness provides an authentic sense of how this history has often been treated, neglected or erased. It is especially meaningful, then, when Takei closes with, "It was gone, Rohwer became a collection of memories."

In the previous two sections I have illustrated the ways vocal rhetorics of narratives of Japanese American incarceration have worked to fill in the emotional gaps of this history. I have documented my own emotional investment in these texts as an example of how this may work. In the conclusion, I focus on the implications of this work and consider how as teacher-scholars we can further amplify vocal rhetorics by including them in our scholarship, and adopt pedagogy that encourages students to better understand their own research subjects.