Filling In the Gaps:

Primary Voices of Japanese American Incarceration

The Core Story: Densho.org

This section looks at the vocal rhetoric in two different ways of telling the history of Japanese American incarceration: 1) a propaganda film produced by the War Relation Authority (WRA) in 1943; and 2) a short video produced by Densho.org in which they splice in moments of the propaganda film with survivors telling their stories. By comparing the vocal rhetorics of each, I hope to illustrate how the differences in tone, pauses, and other important aural aspects of meaning contribute to a multivocal account of Japanese American incarceration, one that acknowledges the previous sanitization without continuing it.

I chose these two narratives because they both attempt to tell what might be seen as the totalizing narrative of incarceration, one that offers a general view of the historical events. They do not aim to tell one person's story or one camp's story but use the individual narratives to provide a general overview, taking pieces to create a cohesive public memory.

"Japanese Relocation" and Densho's "American Concentration Camps"

Milton Eisenhower, younger brother of Dwight D. Eisenhower, acted as the director of the WRA from 1942–43. During his short reign, he directed, wrote, narrated, and starred in the propaganda short film Japanese Relocation (Eisenhower, 1943). The 9-minute-and-40-second film explained, and justified, the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II. In the film, Eisenhower described Japanese Americans as "loyal," "willing," and "happy to make the sacrifice."

It's worth noting that Eisenhower himself opposed mass incarceration, even suggesting that women and children should be left in their homes on the West coast. Perhaps this accounts for many moments in the script that acknowledge the difficulties for Japanese Americans (though he did not ever refer to the incarceration as unjust).

Densho has produced a series of short films that aim to tell what they call the "core story." While there are five such films, I've decided to focus on American Concentration Camps (Densho, 2015), which included descriptions of removal and incarceration at assembly centers and later concentration camps. In this short film, clips from Japanese Relocation were used, as well as a narrator and oral histories from Masao Watanabe and Helena Christ.

In Japanese Relocation, Eisenhower's voice was the only one present throughout the film, unlike American Concentration Camps, where five different voices are featured. Other auditory elements of Japanese Relocation included music that has an official, almost march-like quality. In 1943, an audience would have recognized the genre, since short informational films such as this were produced often during World War II. The entirety of Japanese Relocation can be seen on YouTube, but since I focus on the parts included in American Concentration Camps, I've embedded the latter video here:

In contrast to Masao Watanabe, Helen Harano Christ, and the narrator, Eisenhower's voice has the somewhat monotonous sound synonymous with hegemonic ideals of white authority. When I hear the voice, it reminds me distinctly of the historian's voice I once heard in a recording of M. NourbeSe Philip's "Discourse on the Logic of Language." I cannot separate these associations from my own reaction to the text, and so I hear and recognize, as many readers will, what feels like an artificiality, the forced cheerfulness. As with most scripted audio, the voice is continuous, omitting the natural pauses that accompany much speech.

The following is a sample of Eisenhower's voice, taken from American Concentration Camps to maintain consistency with audio files:

In describing the racetrack, Eisenhower used continuous speech with little to no natural pauses. The emphasis in Eisenhower's speech is placed on "army," "housing," "plenty," and "healthful," visible through the spikes. The voice gets lower through the sentence "plenty of healthful, nourishing food for all." This emphasis highlights the positives—that there was an abundance of "healthful" food. I also find the tone somewhat infantilizing, assuring the audience that the Army is providing for the Japanese Americans like children. I find the sound of this voice numbing, to a degree; the emotional response it elicits is something near indignation at the rosy treatment.

When we compare Eisenhower's description to Watanabe's, which precedes Eisenhower in the film, we hear and see the clear differences. Watanabe's speech is not scripted and feels more like a conversation. He used words such as "crap" and "heck" and talked about his experience. His voice was also deep, but it had a raspy quality. These natural speech patterns help to fill in the “emotional” gaps of the event.

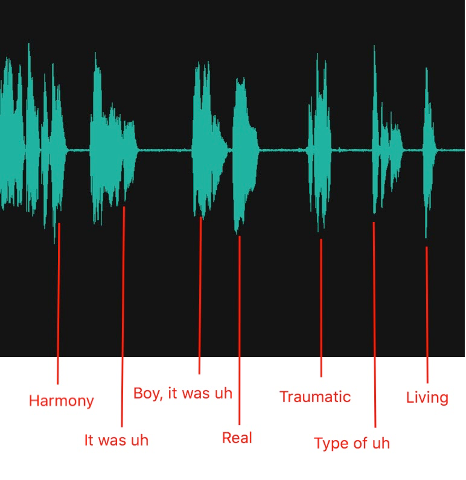

Like Eisenhower, when Wantanabe was describing the Puyallup Fairgrounds prior to his imprisonment there, few pauses exist. Once the story moved into how Wantanabe and his family were put in the same stalls as the animals, the natural pauses are evident. As a listener, I am moved by these natural pauses; I know the feeling of telling a difficult story and the way the pauses act as barriers to the information—that we stop, our brains finding the right word, and our bodies preparing for the effect of sharing. I have an emotional response to this clip, and I believe it is in large part due these pauses. The largest pauses began at "They had a hell of a lot of nerve calling it Camp Harmony," and when Watanabe said, "harmony," the volume increased. The following is a picture of the audio with labels to indicate where the words fall between pauses.

The repetition of "uh" acts as another kind of pause, a filler speech act. The word "traumatic" feels sharp, as the middle syllable "a" is emphasized. Wantanabe's description is difficult to listen to because it highlights the trauma of an individual, rather than providing information about what was generally provided to incarcerees. Later, when Eisenhower acknowledged the difficulties of the experience by saying, "Relocation centers are not normal and probably never can be," his tone became softer, and he made greater use of pauses.

Despite this, it's clear that the statement itself is easy to say. The scripted element does not include fillers. It reminds me of a news anchor reporting a sad event; the tone is adopted, but ultimately Eisenhower's goal is to inform. In his efforts to assuage the fears of a public that may be uncomfortable with the idea of incarcerating American citizens, Eisenhower must create a positive view by pushing through the difficulties, rather than lingering on them.

The Densho video, however, aimed to provide the audience with information about the experience rather than just the historical event. And so they chose Wantanabe's description, which lingers on, rather than pushes through, the difficult moments. This lingering fills in significant gaps of meaning, as it captures the traumatic experiences of those incarcerated. Helen Harano Christ's story has similar qualities, but whereas Wantanabe made use of emphasis and pause, Christ used short laughter and elongates sounds. The following clip includes two moments spliced together.

When Christ described herself as "wistful for what was outside the fence," she included small laughter in the word fence. She continued, "you know, I used to be able to do that" with laughter accompanying the words "to do that." The laughter acts as a cushion to the trauma of the story. It feels like the uncomfortable, forced laughter I would use when sharing something that has the potential to cause someone else pain to hear. And this story is indeed emotionally difficult to hear. When she elongated the "s" in "s-s-nake," with pauses between the first sound and last, I am particularly moved. Through this noise, we feel the slithering of the snake itself, while also acknowledging the difficulty in sharing the story.

Similar to when I listen to Wantanabe, I have a strong reaction to Christ's story. Rather than indignation, I feel sadness. As of December 2020, five comments illustrate the reactions of general audience members on YouTube:

"I live just blocks from puyallup fairgrounds. Before i knew of its history i always felt a saddness when i would drive past it and now even more so. Thank you for sharing this. It is important to know our countrys history."

"It's such a sad story. What's mean to get a Citizenship? Are you than an American or still not?"

"This is mean. No one should be incarcerated unless you are a criminal. Also, i don't remember learning this in history. Don't they say that we need to learn from history so we dont make the same mistake?? This is so shameful."

"Shame on them! This Is horrible. how can you do that to people?"

While four comments cannot provide a thorough look at audience response, the reactions mirror what Jenefer Robinson (2005) described as "emotional investment," when the audience cares for the subject, is attentive, has a bodily response, and offers a "non-cognitive affective appraisal" that may correspond to basic emotions, "This is a threat! This is an offence! This is wonderful!" (p. 114). The reactions above mirror these examples: "This is so shameful." "This is mean." "Shame on them!" "It's such a sad story."

The intimacy of voice contributes to an emotional response. The YouTube comments also illustrate the accessibility of the Densho video and oral histories included. The audience is not limited to scholars or any particular community, but relies on narrative forms and vocal rhetoric to appeal to a more general audience, one who may not have heard the history before. In the Rohwer Soundscape section, I consider how placing digital voice within a physical space further assists audiences in filling these important “emotional” gaps of meaning.