Discussion

Profile Pictures

A review of the images used on the Disability March website revealed similar contrasts between images that included markers signaling disability and those that omitted or downplayed these signs. Visibility was a theme across a majority of the profiles, as more than two-thirds included profile pictures showing the face of the person authoring the profile. By making themselves visible as part of the Disability March, this group implicitly claimed disability as part of their identities and pointed to a contrast between their normative presentations on the site and commonly held stereotypes about disability. Many of these photos fell into line with common Western assumptions about what constitutes attractiveness and assertiveness on social media sites (see Vacharkulksemsuk et al., 2016). More than half chose images in which they looked directly into the camera, suggesting an openness, a desire to be recognized and counted, as well as equity between the protestor and viewer. Exemplifying this style of photo was Cynthia Dunn-Selph (2017), who posted a standard selfie-style head shot in which she smiled into the camera while standing in front of a cabinet or closet. The profile contained no specific reference to disability, either in image or text. Images like this reject the tropes identified by Garland-Thomson (2011) by showing disability as a mainstream experience indistinguishable from the experience of other, similarly gregarious participants on social media sites.

Other profiles similarly made implicit reference to common cause between disabled and non-disabled participants in the larger Women's March. Approximately 90 profiles featured women in pussy hats—pink or red knit hats worn as a reminder of Trump's remarks promoting sexual violence against women. In other respects, these profile pictures were often quite conventional in appearance. For instance, Ruthellen Hooker Sutton (2017) appeared in front of a closet, smiling, making eye contact with the camera, and wearing a red knit pussy hat. Hats like hers recall stereotypes about women—that they are engaged in cloistered domestic activities (i.e., knitting at home) and, if single, that they may share a particular affinity with cats like the stereotypical old maid who inhabits a marginal position in society. However, by making clear reference to hidden anatomy—by making the vulgar visible—the hats bucked societal expectations to criticize Trump's own vulgar behavior. Pussy hats came to symbolize the larger Women's March in 2017 ("Second lives of pussy hats," 2018). As such, in the Disability March, they normalized participants within the context of feminist protest even as they signified misfit or discord with societal norms.

By making no visible reference to disability, a large number of the profiles on the Disability March work at odds with stereotypical representations of disabled people as wondrous, exotic, sentimental, or realistic object lessons. A smaller subset (n=235) referenced disability by including medical equipment or textual indicators within the image. While connecting the protestor more overtly to disabled identity, some of these profiles also included signs of common cause between disabled and non-disabled experiences. For instance, Sally Hoffman-May's (2017) profile figured a domestic scene including a fresh-baked cake, an apron, and kitchen implements in the background. A banner over the image referenced myasthenia gravis, creating a juxtaposition between the smiling woman pictured and stereotypical assumptions about disability as either an exotic or pitiable state of being. While the image countered some stereotypes about disability as the frightening other, it did so by embracing other tropes about women as nurturing, domestic laborers. The image may also be read as further playing into the medical model of disability by suggesting that the MG Walk will help produce a "world without myasthenia gravis"—presumably by raising money for research and medical interventions. Taken as a whole, profiles like this counter othering narratives about disability as exotic or wondrous while at the same time playing to more traditional or stereotypical ideas about sickness and femininity.

Other images with specific references to disability likewise countered the tropes identified by Garland-Thomson. Some of these images left the protestor entirely aside, showing only the medical equipment that sustained or supported them. For instance, MS John's profile (2017) contained an image of an empty wheelchair sitting at the edge of a precipice with a view of the landscape below. The image could be interpreted as critically enacting the way that society often renders the disabled person invisible—a point made throughout Garland-Thomson's (2011) work on representations of disability. Whether representing disability as wondrous, exotic, tragic, or instructive, each of the traditional tropes effectively erases the actual experiences of the disabled subject of the image, instead opting to convey particular messages to the able-bodied viewer. MS John's (2017) profile picture carried this tendency to its logical endpoint by literally obscuring the protestor themself. An accompanying note in the profile statement indicated that John was not pictured because of being "bed-ridden" with multiple sclerosis. MS John's profile hinted at the ways that a protest like the Women's March actually silences swathes of the population who might lack the requisite mobility to participate. The misfitting in this image is sharper than elsewhere on the website, dramatizing MS John's invisibility while registering dissent through participation in the Disability March.

Others like angie river's profile (2017) included images of the protestor but provided a similar counter-point to representations of disability as wondrous or sentimental. River's post showed a woman in bed, unsmiling, and included no signifiers suggesting medical intervention or progress toward health. The image is not sentimental, nor does it include a call for intervention by able-bodied viewers. Rather, the direct-to-camera gaze implied equality between the viewer of the image and the subject, again defying expectations that the feeble disabled body may wish to be saved or remedied. In this sense, the profile provided a counter narrative at odds with prevailing notions of disability as a temporary disorder soon corrected by medical intervention.

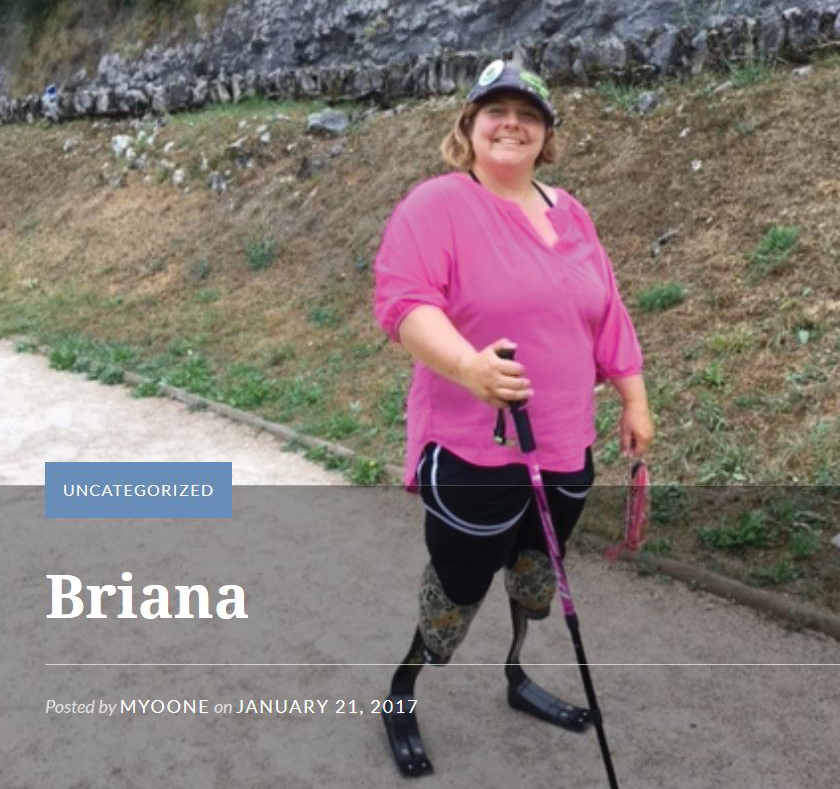

Other profiles similarly complicated the trope of disability as wondrous or extraordinary. Some 92 profiles showed people with disabilities engaged in a sport or organized physical activity, suggesting that the person pictured was behaving like an able-bodied person despite physical challenges. For instance, Niki Beecher (2017) appeared on a trail in fall, being pulled in a sulky by two husky dogs. Briana (2017), a double amputee, appeared smiling and walking on an outdoor trail. Sophia (2017) was pictured in a wheelchair on a running track. And, finally, Laura Denney (2017) appeared in a home, caring for two children as she stood on crutches.

Each of these images suggested remarkable physical achievement, much as in the wondrous trope identified by Garland-Thomson (2011). However, signs of the wondrous were also subverted or tempered by realism in each of the images. All four pictures included assistive devices, showing people in motion with the help of dogs, canes, wheelchairs, or crutches. Denney's (2017) picture included a glimpse of household disorder, with a child's head peeking into the periphery of the frame and a picture that may be a little askew on the wall. The juxtaposition of extraordinary effort and realism allowed the people pictured to read as both mainstream—able-bodied, active, domestic—and misfits at the same time. Adaptability was a key message in these images—the ability to adjust and thrive despite social and cultural limitations.

Another set of profiles provided counter-narratives to the wondrous through use of superhero costumes and poses. For instance, Allegra (2017) appeared dressed as Wonder Woman while holding a stuffed cat that was also dressed in superhero guise. Wendy H. (2017) posed against an Arthritis Foundation logo with a flexed bicep cutout superimposed over her own arm. Madison Noelle (2017) showed herself with a flexed arm, using a breathing tube, yet standing alongside a sign that read, "Be Your Own Kind of Beautiful." Several protestors like Becky (2017) also adopted Rosie the Riveter poses in their profile pictures. They appeared with raised, flexed arms, referencing the women who entered the workplace during World War II.

All of these images again invoked and subverted the rhetoric of the wondrous. The women who adopted superhero poses left obvious signs in their pictures that they were posing: Allegra's image included a stuffed animal dressed in the same costume as the protestor, making it clear that both were pretending or temporarily adopting another identity. Wendy H.'s (2017) image showed a woman holding the cut-out of a muscular arm while leaving the actual, arthritic arm visible. Madison Noelle's (2017) image showed a woman adopting the flexed-arm pose of a superhero while she remained hooked up to, and sustained by, medical equipment. These signs of realism created images that—like the previous group of athletic shots—suggested the protestors' complex messages about the actual experience of disability. Each of these images invited viewers to expand their perception of heroism by showing sick and struggling people in those roles. By mixing tropes, these profiles posited a new understanding of what it means to be both disabled and empowered.

As with the examination of the identity statements used in the Disability March, an examination of images reveals a range of messages about disability. While some profiles removed all signs of difference between disabled and able-bodied experiences, others placed medical equipment, assistive devices, and subverted hero tropes in the foreground. In the context of the Disability March, each group of profiles reads as a call for greater inclusion, though communicating different experiences and understandings of disability.

Accessibility Highlight Video: Skip Navigation (Transcript)