Discussion

Profile Statements

Participants in the Disability March varied in their use of person-first and identity-first language as well as the extent to which they explicitly addressed or named disability. Some profiles called into question ableist social norms by foregrounding the disabled identity of the protestor in question while others, by eliding the difference between themselves and society at large, implicitly made a call for equal agency and voice. Profiles throughout the Disability March often show this push and pull of foregrounding or eliding difference. This section, therefore, hearkens back to work by Rosemarie Garland-Thomson (2011) and Maria Bee Christensen-Strynø (2016) on mainstreaming and misfitting representations of disability. It also recalls the political/relational model of disability, which called for careful consideration of the ways that categories like disability are constructed and to whose advantage.

Some profiles on the Disability March foreground disability in the text and, in so doing, create space for the protestor to address structural and societal problems that serve to marginalize. Forty-four percent of all profiles fall into this category, as they name a specific disability—many of them superficially invisible, including mental illness and autoimmune diseases like multiple sclerosis. Rosie Doherty (2017), for instance, began her profile statement by noting, "I am a 39 year old living with Rheumatoid, Fibromyalgia, Systemic Lupus, Osteathritis, anxiety and sever [sic] depression." Doherty chose to foreground a series of medical diagnoses that would not have been apparent by seeing her image. This choice may force the viewer to question ableist assumptions about what disability looks like, who is included in this category, and what types of privileges and services that person may be able to access. In the remainder of her statement, she pushed back against assumptions about disability by noting that disabled women are "so much stronger than we are given credit for." Ultimately, by pointing out her differences or "misfit," Doherty suggested a reframing of disability. Profiles like hers effectively called attention to disability in order to bolster the march's larger call for equity and inclusion.

While some Disability March profiles challenged common conceptions by making disability visible, other profiles made no explicit reference to disability and, in so doing, implied that disabled people share common cause with society at large. Indeed, as previously noted, the majority of profile statements (56%) did not name specific disabilities. Many of these protestors chose to identify themselves by referring to their professions, personality traits, appearance, or relationships. For instance, Joy Hart Carter (2017) noted only that it was her "duty" to join the march, describing herself as "an older woman with short hair and glasses." By leaving references to disability out of her profile statement, Carter chose to center the experiences she shares with mainstream society. When viewed alongside her photo, Carter's statement implied that she was motivated to advocate for equality and inclusion in part by a maternal need to protect loved ones. Her profile, in effect, insisted on the similarities between disabled protestors and other women with friends and families.

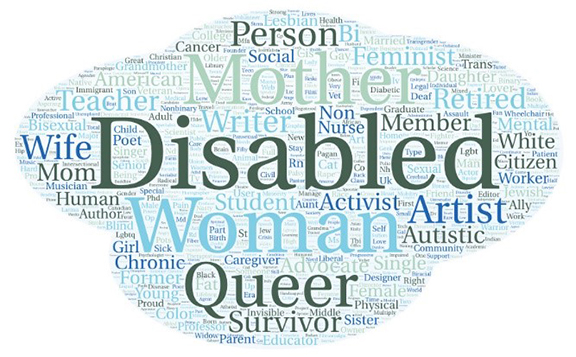

To summarize some of the choices made in Disability March profiles, the following word cloud captures the most common identity words that appeared when protestors introduced themselves as "I am [x]." In these cases, the most common identity choice was "disabled" but this was closely followed by woman, mother, queer, person, and artist. It should be noted that there are limitations in extrapolating too much from these choices. For instance, some disabilities don't fit neatly into the "I am" syntactic structure. However, on the whole, these choices suggest differences between profiles that foregrounded disability and those that downplayed it in favor of naming mainstream identities such as mother or human. These choices echo those made by protestors like Rosie Doherty and Jay Hart Carter—in one case, addressing disability directly and, in the other, highlighting other identities.

Along similar lines are the differences uncovered through an examination of person-first and identity-first language in profiles. Protestors varied in their syntactic choices when they made identity statements, with 25% using person-first constructions to refer to disability while the remaining 75% either didn't identify or used identity-first language. The person-first group often used passive sentence constructions to refer to disabilities, noting that they were disabled by, recovering from, dealing with, suffering from, restrained by, struggling with, plagued with, limited by, labeled as, stricken with, challenged by, or sidelined with various medical conditions. For instance, Sandra, Christian Heretic (2017), named herself as a "prophet, priestess, and sage" who had been "cloistered by chronic illness." By one interpretation, this type of construction suggested distance between Sandra and her disability, although in this case, she also used the imagery of the cloister to further underline her claim to divine inspiration or authority. For others who similarly used passive constructions, this choice could be read as another attempt to mainstream the protestors' experiences, where disability is represented as a temporary or external condition.

In contrast were those who used identity-first constructions to describe their disabilities. This group was larger than the person-first group, which may reflect the activist bent that pervades the Disability March. Identity-first protestors included a sizable contingent of people like Rosie Doherty who identified as having invisible disabilities such as depression, fibromyalgia, and chronic pain. By identifying disability as an intrinsic part of their identity, this group effectively pointed out misfit between themselves and society despite their normative external appearance. By making themselves visible, this group positioned itself to call for changes to structures and systems that tended to exclude them.

While it is useful to consider the effect of identity statements alone, more complex interpretations come into play when considering these statements alongside their accompanying images. When taken as a whole, it becomes apparent that profiles often enact both misfit and mainstreaming through juxtapositions of image and text. For instance, Jenn Hyla (2017) appeared in her photo seated at a kitchen table. Her pose was unremarkable but she described herself as having "neurological Lyme disease," an invisible illness that left her "bankrupt and bedridden." The only other marker of Hyla's disability were the piles of discarded medication bottles at her feet. She wore a tank-top that read "Freedom"—in this context, a message that could be read as an ironic reference to her dependence on medical treatments, insurance, and the healthcare industry. At this charged political moment, "freedom" might ordinarily read to Americans as an invocation of shared democratic values, but Hyla's profile invited viewers to consider disruptions to freedom that actually exist, albeit invisibly. In this sense, her profile juxtaposed a mainstream pose against a story about misfit—that is, her struggle to access health care and financial security. Through this juxtaposition, her profile invited consideration of the societal and cultural barriers that prevent some Americans from achieving real freedom in their lives.

Similarly, Heidi Lasher-Oakes (2017) identified herself both as a disabled person and a person with many other identities. She wrote, "I am so many other things besides disabled," and proceeded to list 39 personal identifiers including academic, daughter, welder, and writer. Only one of these—patient—referred to disability. In effect, she showed both the mainstream and misfitting parts of her identity. This theme is suggested as well in Lasher-Oakes' profile picture, in which her body is indistinct—a shadow like any other—although one might surmise that she is using crutches that serve as a medical intervention in her everyday life. This profile recalls the political/relational model of disability because it implicitly acknowledges the role of medical intervention in Lasher-Oakes' life while pushing back against societal efforts to reduce her to merely a patient or cure-in-progress. The combination of image and text in Lasher-Oakes' profile comprise a nuanced identity statement that combines both mainstreaming and misfitting to advocate for greater inclusion.

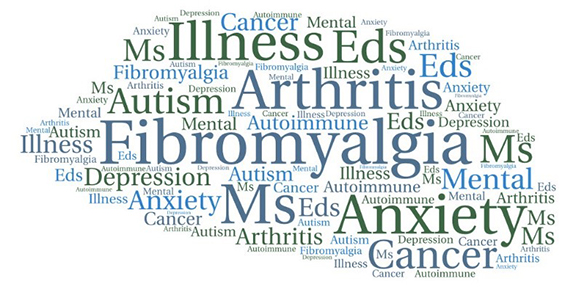

While the Disability March makes a bid to mainstream minority experiences, it should be noted that the protest itself appears to have drawn a relatively narrow range of participants. Although only a small number of the protestors identified themselves by race (n=34 as Caucasian/white and approximately n=14 as BIPOC), a review of the profiles on the website suggests relatively little racial diversity. A cluster of professions also appeared frequently in the profiles, including artist (n=81), teacher (n=75), retired (n=71), writer (n=62), and activist (n=58). While it is difficult to draw sweeping conclusions from these stated professions, they do suggest belonging to middle-class economic status. Stated disability types were also fairly narrow in range, with chronic pain and mental illness ranking high in mentions, as well as autoimmune diseases and syndromes like Ehlers-Danlos (see Figure 10). Invisible illnesses were a plurality in the march, and it is noteworthy as well that only a small number of the protestors (n=92) indicated in their statements that they had posted on behalf of a disabled person. The implication, then, is that the majority of the participants in the Disability March had enough mobility and comfort with blogging interfaces to contribute their own profiles, although it appears that most posts were made public by a handful of moderators or volunteers.

Each of these observations suggests that, while the protest represented an attempt to widen mainstream acceptance of alternative experiences, the project's reach may have been relatively narrow. Indeed, these constraints on the project are understandable considering that the organizers also identified themselves as activists and writers and likely tapped their own social networks in recruiting participants (Disability March, "About Us," 2017). While it would be foolhardy to assume too much based on visual appearance, the apparent lack of diversity in the Disability March does line up with other critiques of disability rights advocacy—that it could do more to engage with intersectional identities around race, class, sexual orientation, and other experiences.

In the end, an examination of identity statements in the Disability March reveal different choices in how protestors chose to represent their disabilities. Some seemed to distance themselves from conditions that they spoke of as a kind of external affliction. Others highlighted otherwise invisible disabilities and called attention to resulting social exclusion. And some protestors juxtaposed these representations in image and text that played off each other in nuanced ways. All profiles alike conveyed the need for greater inclusion of various identities—whether by suggesting that able-bodied and disabled people share a common experience, or by calling attention to harmful social constraints that exist for those with even invisible disabilities, or by doing both things at the same time.

Accessibility Highlight Video: Color Contrast (Transcript)