Analysis

Our videos, in one sense, reflect a plurality of approaches to composing. We shape and are shaped by our spaces in different ways. We acclimate to our composing surfaces in various ways. We do our writing work in different ways.

However, our diverse practices in composing share some commonalities—some threads and themes visible across the videos. These threads and themes merit attention. If we, as composition scholars and instructors, are to continue to pay sound, solid attention to multimodal composing processes, we need lenses—lenses that emerge from composing processes themselves—to understand the ways in which we orient ourselves to writing work in the 21st century.

Below, we present some of these trends and themes, offer brief explanations, and point toward specific examples where the trends are evident. Although we know lists are value-laden despite our intent otherwise, we do not want to present the trends below in a hierarchical or value-laden way; the list of themes is agnostic.

Composing Requires Using Different Mediums, Tools, and Interfaces

- composing happens in and across different mediums (typing and handwriting seem most common)

- writing happens in and on other spaces, including notebooks, sticky notes, smart phones, keyboards, and often within one writing session

- composing with each medium serves, for each composer, a different purpose

Jessica and Layne both move between writing with pen and notebook and writing on the screen.

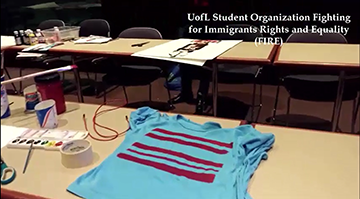

Sara moves between physical space and community conversations in dialogues that take place on the screen as she researches her areas of study.

Composing Requires Others

- writing-related collaborations happens in different ways and for different purposes

- composing with others can happen within a room or within a shared document, in a writing workshop session or in an informal conversation

Sara's video opens with a shot of a shared/conference-room screen in which one person is typing, but we hear multiple voices composing and contributing.

Michael workshops and brainstorms with Dan, and also co-creates his slam poetry as he presents to and performs with his audience.

Composing is tied to the human experience of time

- writing is sedimented and intersected by life experiences occurring during our composing

- composing isn't limited to a particular time when a writer is sitting at a notebook or a computer

- composing "time" is thus temporally porous

Ashanka captions the work she's doing as she composes, which not only includes reading and note-taking, but also texting and gameplay.

Michelle moves among various spaces while working on projects: home, coffee shops, the gym, etc. In this way, motion and time become part of her composing process.

Caitlin demonstrates the embodied relationship between time and composition through the use of both fast and slow motion in her video.

Composing happens beyond alphabetic text on the page or screen

- composing is inherently multimodal

- composing is an ongoing process that occurs while driving, running, interacting with others, and other mundane everyday events

- composing happens in the human mind—itself a complex, networked, poorly understood space—meaning that composing is happening constantly

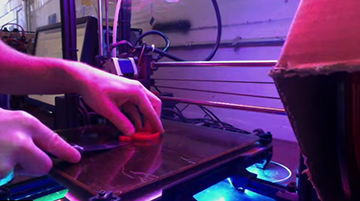

Rick composes his work with a 3D printer.

Michael composes his work by performing—using his voice and his body to both write and perform his slam poetry.

Laura talks about the need to move as an integral part of her composing process.

Composing happens with/through bodies

- composing is not just a cognitive act; it is a material act

- writing's materiality has to do, of course, with the products of composing, but also the physical body composing

- while composing, the body has demands; the body interrupts, intervenes, processes, digests, and more

Caitlin's video, focused as it is on crip time and composing with a disabled body, is perhaps the most obvious window into composing happening with/through bodies.

Amy's baby and his needs physically impact and influence the composing work Amy does.

Michelle documents the way in which she arranges her physical space, across actual physical locations.

Sara's video reflects her bicultural and bilingual embodiment as she moves in and out of various spaces, conversations, and contexts, to emerge as a Latina scholar working with and for social justice.

Composing revolves around influences, collaborations, and intertextual reciprocities

- writing habits and styles are shaped by what came before us; additionally, our collaborations with one another in and out of class influence our video compositions

- composing influences are often outrightly, visibly expressed in our composing processes

- the relationship between texts and those who make texts has the potential to motivate processes that will result in other texts

Jon discusses the influence of fictional works on his process.

Amy discusses the notion of going home, with implicit arguments for the value of home, community, and so on.

Sara draws on her experiences of shuttling between languages, mediums, and community spaces in order to bridge spaces that are often socially constructed as separate.

Khirsten employs black noise as a resource and fund of knowledge as she emerges as a Black woman scholar in her field. The black noise she listens to mirrors elements (cutting, sampling, mixing, blending) of her own process.

Laura discusses how integral interaction with others (her husband, colleagues, etc.) is to her composing process.

What is Visible and What is Not

Our composing and what our processes revealed tell us much about the embodied, connected, always already happening nature of writing. What isn't perhaps as visible here are the ways in which our composing practices rub up against, fit into, or even explode metanarratives of queerness, race, disability, mothering/hood, and more. Both individually and as members of a larger academic community, we are wrestling with these metanarratives and how they shape our practices.

Next > Conclusions