The first issue of one of the first European fanzines dedicated to Bruce Springsteen, Point Blank, created by Dan French (1980), opens with a masthead that echoes concrete poetry: an ink outline of Springsteen, the neck of his guitar coming out of a barely visible left hand, his body skinned with typed acknowledgements, credits, and production and printing information. The first word: "Greetings," a nod to Springsteen's first album, Greetings from Asbury Park, NJ. French describes Point Blank as "an unofficial and casual fanzine for Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band. It is non-profit-making, aiming only to promote the improvement of conditions for Springsteen fans, particularly the deprived British variety." Handwritten on the neck of the guitar: "No. 1 in a possible series. . ." (French, 1980, p. 1). Point Blank had a run of 12 issues, ending in 1992 with a special double issue dedicated to Springsteen's 1992 tour of the United Kingdom.

What are you doing?

"Into the Sunset: Point Blank in the Promised Land," pages 12-13, drafts, 1982. Used with permission.

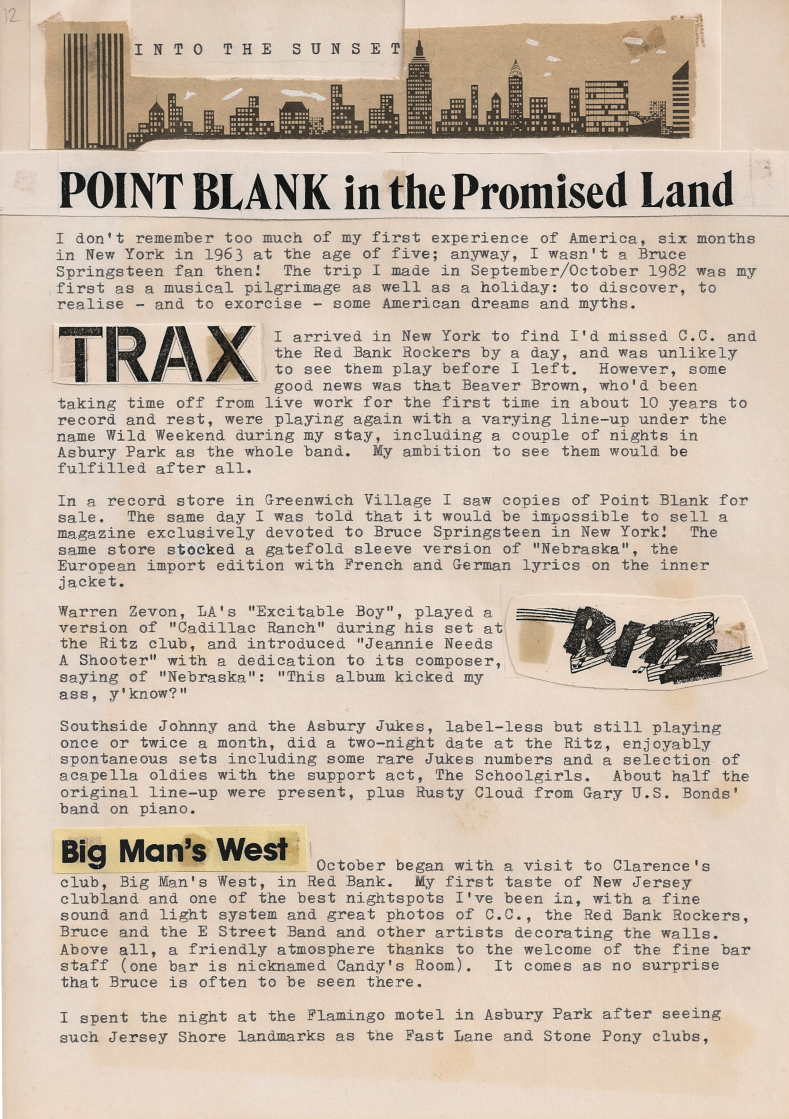

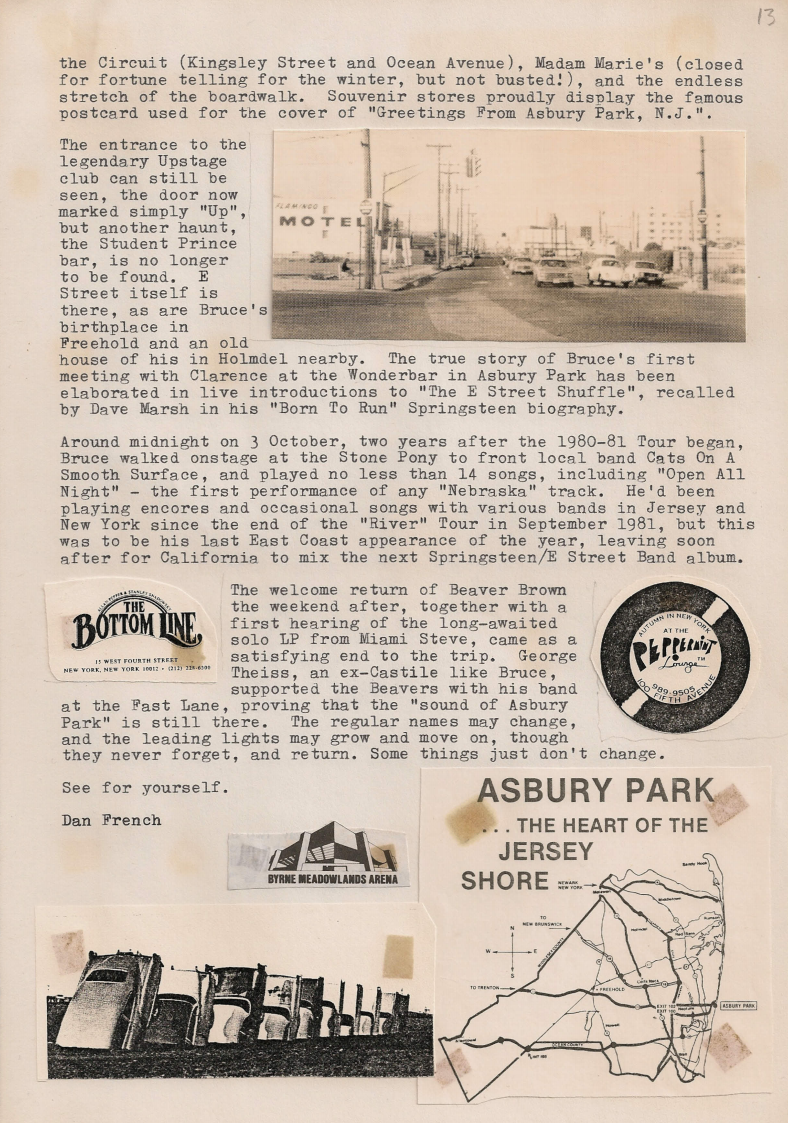

In 2010, French created a free online archive of Wild and Innocent Productions materials: scanned PDFs of all Point Blank issues; a five-issue publication, Songs to Orphans, which provided lyrics to many of Springsteen's unreleased songs; and many work–product documents. One of those documents is a scan of a two-page draft of an article, "Into the Sunset: Point Blank in the Promised Land," which appeared in the 1982 issue. It describes French's September to October 1982 "musical pilgrimage . . . to discover, to realize—and to exorcise—some American dreams and myths." The draft is evidence of the cut-and-tape process French used to create the article. Content was typed on a typewriter, leaving space for taped-on cut-outs of club names, photographs of Asbury Park and the Cadillac Ranch, a map of Asbury Park, and a graphic of the New York City skyline. Brown stains reveal tape used to attach the cut-outs to the article, chemical processes associated with composing, and the breakdown of technologies of writing over time.

The cut-and-tape draft is an artifact of early-1980s writing technologies: paper, scissors, tape, whiteout, typewriters. It reveals the multimodal, media-rich composing process of early fanzines and literacies associated with being a fan. Henry Jenkins (2013) has observed that "[f]andom celebrates not exceptional texts but rather exceptional readings (though its interpretive practice makes it impossible to maintain a clear or precise distinction between the two)" (p. 284). Several years later, he elaborated on his initial description: "[o]ne becomes a 'fan' not by being a regular viewer of a particular kind of program but by translating that viewing into some kind of cultural activity. . . . [C]onsumption naturally sparks production, reading generates writing, until the terms seem logically inseparable . . ." (Jenkins, 2006b, p. 41). Fans are not passive consumers; they are active readers and sophisticated creators.

In her book-length ethnography of women Star Trek fanzine readers and writers, Camille Bacon-Smith (1992) described the creation of fanzines to be a "subversive act" where communities of fans "bend popular culture artifacts" (p. 1). Michelle Comstock (2001) argued that writers and editors of fanzines are "collectively engaged in forms of writing and writing instruction that challenge . . . dominant notions of the author as an individualized, bodiless space" (p. 383). Brenda M. Helmbrecht and Meredith A. Love's (2009) analysis of the zines Bitch and Bust showed "a feminist movement that both absorbs and reconfigures the progress of its feminist 'foremothers'" (p. 151). Mirko Tobias Schäfer (2010) has labeled these kinds of activities "explicit participation" as they "require explicit action to participate in a community and consciously produce media texts and artifacts" (p. 44). Fans exist at the intersection of popular culture, interpretation, and textual production, where they "create social structures, ecologies, rituals, and traditions of their own" (Duffett, 2013b, p. 17) and are "constantly making their own cultural environment from the cultural resources that are available to them" (Grossberg, 1992, p. 53).

What are you doing?

Girltrueheart (2014) said one result of moving to Twitter has been the emergence of new words added to the Springsteen fan discourse community, some of which she named and some of which she "witnessed being born" (personal communication, March 9, 2014). These include:

With the shift from analog to digital, many fan practices, too, moved online to web sites, blogs, forums, wikis, archives, and, of course, Twitter. Online spaces have remediated many traditional fan activities, but also have afforded newer and easier opportunities for sharing and creating texts and connecting with fellow fans. One of the greatest changes has been visibility: "it is hard in the Internet era not to see and therefore to say that fans are, at best, communicative, imaginative, communal, expert, interesting, and intelligent. . . . [F]andom seems to be at the forefront of an astute, techno-savvy culture" (Duffett, 2013a, p. 4). Kyle Stedman (2012), for example, has studied the practices of fans who remix video, remix audio, and compose fan fiction in an effort to consider what we might "learn from the self-sponsored remixing efforts of individuals in existing communities who compose, peer review, distribute, and discuss work online" (p. 107). His findings led him to describe a "Remix Literate Composer" and suggest "multimodal, multivocal conversations are crucial skills for individuals who want to engage in civic discourse and personal connections, both on and off the computer" (Stedman, 2012, p. 120).

What's happening?

"I'm a very big fan myself. I have the mentality of a fan. I can't hear a bad word about Elvis Presley, Hank Williams, John Fogerty, Jackson Browne, Southside Johnny, because I am a relentless fan of all those people. I would take great pains to meet all of them, in so far [as] they are still alive, of course. . . 'Fan' means to me what I said about Elvis: to love someone unconditionally because what that person is doing makes part of your own dreams come true. . . ."—Bruce Springsteen in a Belgian interview by Marc Didden (1982), translated by Ria Aeschlimann, reprinted in Point Blank.

Rik Hunter (2011) has considered the collaborative writing practices on the World of Warcraft wiki and Sarah Summers (2010) has investigated how girls and young women compose in the popular "Twilight is so Anti-Feminist that I want to Cry" discussion thread. Summers's (2010) study "reveals the way that convergence culture provides a link between private reading experiences and social and political projects, such as the need for feminist e-spaces" (p. 323). In a special issue of Transformative Works and Cultures on "Fan/Remix Video," Virginia Kuhn (2012) has argued for a formulation of remix grounded in classical rhetoric by analyzing Star Trek and other fan remixes. In the same issue as Kuhn, Tisha Turk and Joshua Johnson (2012) advanced the notion of an "ecology of vidding" (when fans place music over video clips), a phrase that deliberately echoes and transforms Marilyn Cooper's seminal 1986 College English article "The Ecology of Writing." Liza Potts (2012), writing in Participations, has further shown how fans on Twitter are confronting social and political issues by discussing how Amanda Palmer and her fans are "rewriting" the relationship among artists, fans, and record labels.

Music fandom can be traced to two of the oldest of new media technologies: the phonograph and, later, radio (Duffett, 2013b, p. 6). According to Lisa Gitelman (2000), in 1907 Thomas Edison's National Phonograph Company grossed over two million dollars in sales of phonographs and records for personal use, suggesting that the "musical phonograph helped define leisure time and space" (p. 85). In the 1920s and '30s, radio stations adopted daily and weekly programming, which resulted in audiences who would tune in to listen to their favorite show or artist, like Benny Goodman or Bing Crosby (Duffett, 2013b, p. 8). In the 1940s, Frank Sinatra became the first major music fan sensation, soon to be followed with the popularization of television by Elvis and the Beatles. All rock 'n' roll musicians exist in their wake, and, with them, all rock 'n' roll fans. In his 2012 South By Southwest Music Conference keynote address, Bruce Springsteen (2012) observed:

Television and Elvis gave us full access to a new language; a new form of communication; a new way of being; a new way of looking; a new way of thinking about sex, about race, about identity, about life; a new way of being an American, a human being and a new way of hearing music. Once Elvis came across the airwaves, once he was heard and seen in action, you could not put the genie back in the bottle. After that moment, there was yesterday, and there was today, and there was a red hot, rockabilly forging of a new tomorrow before your very eyes.

Later, Springsteen (2012) described seeing the Meet the Beatles record cover while at a five and dime: "It was like the silent gods of Olympus. Your future was just sort of staring you in the face. . . . Then in some fanzine I came across a picture of The Beatles in Hamburg. They had on the leather jackets and the slick-backed pompadours, they had acned faces. I said, 'Hey, wait a minute, those are the guys I grew up with, you know, only they're Liverpool wharf rats.'" Music fandom is inextricably linked to analog and electronic technologies: grooved vinyl, cardboard album covers, film photography, radio waves, telephone lines, fiber optic cables, servers, computers, cell phones, apps, and so on.

Lucy Bennett (2012a), however, has noted the paucity of academic studies on music fandom—especially, I would add, those that take into consideration fans' use of composing technologies to affect their fandom. Bennett's work on the impact of social media technologies on U2, Tori Amos, R.E.M., and Lady Gaga fans (2011; 2012b; 2013; 2014) has resulted in significant insight into how multiple fans employ technology in ways unique to their fan communities, complicating the long-debunked but still often-repeated myth that all fans behave the same in all settings.

Indeed, it is not my goal to make a case about all fans in all concert situations. Rather, my study is an attempt to learn more about the composing practices of members of the Springsteen community at or tweeting about one particular concert so we can learn more about the various ways people are writing in public online spaces. Each concert, like each composed text, is different. I will not be making generalizations about fandom overall. Daniel Cavicchi's (1998) observation about Springsteen concerts is instructive:

[A Springsteen] concert represents a powerful meeting of the various forces and people and ideas involved in their participation in musical life. The excitement of participation, the feeling of connection with Springsteen, the interaction of fans and other audience members, the rituals, the energy, the empowerment, the communal feeling, the evaluation and discussion: together, they enact the meaning of fandom. They shape and anchor fans' sense of who they are and where they belong. (p. 37)

Cavicchi's repeated use of the definite article is significant. He is rooting his discussion about the text, a concert, in the activities of Springsteen fans alone. The excitement, the rituals, the communal feeling . . . they are textual engagements, grounded in the space of the concert, influenced by Springsteen fan community practices, and tempered by individual reactions. Lawrence Grossberg (1992) argued that "the relationship between the audience and popular texts is an active and productive one. . . . People are constantly struggling, not merely to figure out what the text means, but to make it mean something that connects to their own lives, experiences, needs, and desires" (p. 52). Despite all the rituals and practices and community spaces, fandom is, at its root, personal. Each record bought, each concert scream, each utterance tweeted is, ultimately, a personal reaction to popular events understood through the lens of community practices and, as here, how they have been expressed through writing.

Track 2: Compose New Tweet?

Track 4: Background and Methodology