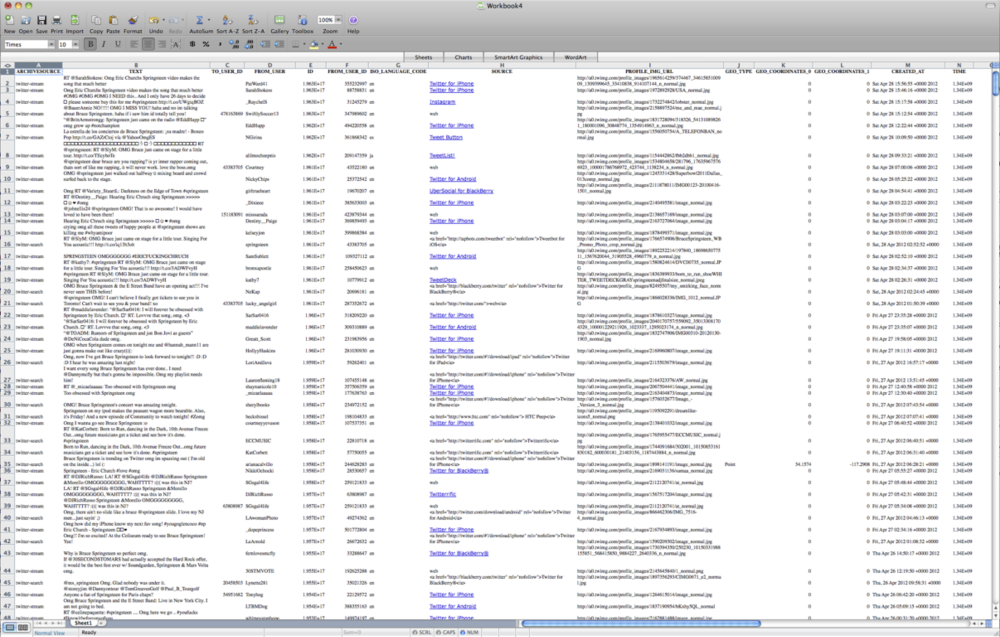

When sitting at one's computer looking at a tweet archive in Excel, perhaps several years after the tweets were published, it is easy to forget that a unique individual in a specific space composed each tweet at a specific time for a specific purpose. Columned in front of a researcher, the light of the monitor illuminating them, the tweets appear immediate, seamless, unified, isolated from time and space.

It is important to step back and remind oneself that each tweet was composed in situ in response to media events unfolding before the author's eyes and with their explicit participation. Authors composed their tweets while at the Izod Center in East Rutherford, NJ, watching Springsteen and the E Street Band perform. Or, they were anticipating the event beforehand or reflecting on the event soon afterward from the calm of their cars or homes. Those who composed tweets while at home or at work or at a coffee shop were participating with a remediated version of the event in Twitter streams on their computers, phones, or tablets.

It is also important to remember that I, as the researcher, archived and sorted these tweets into a corpus based on a search for the keyword "Springsteen" and filtered by time and date constraints. Unless someone else was monitoring a keyword search of "Springsteen," this group of tweets has never been brought together before and very likely will never be brought together again. In her analysis of a corpus created by archiving tweets with the keyword "Obama" in the hours after the 2008 presidential election, Michele Zappavigna (2011) took pains to describe the problematic nature of the term "community" when applied to non-hashtag keyword corpuses. It is also difficult for me to describe what I have collected as a community or even virtual community. Similarly, it is problematic to consider the collected tweets as an "information ecology," as Brian McNely (2010) was able to adapt Bonnie A. Nardi and Vicki L. O'Day's (1999) concept to describe tweets for a convention, because in my corpus there is no hashtag grounding the tweets in a specific virtual classification space (Wolff, 2015).

Rather than discussing the corpus as a whole, this study makes clear the importance of considering and discussing each tweet individually. This corpus is not a community; it is an archive of sorted texts compiled to afford data analysis. However, each individual tweet—each individual composition—reifies one or more Springsteen fan community practices. A grounded theory analysis of Bruce Springsteen fan tweets from the Izod Center concert reveals a complex system of texts, technologies, and human actions organized in response to a media event. Margaret A. Syverson (1999) defined a complex system as "a network of independent agents—people, atoms, neurons, or molecules, for instance—[that] act and interact in parallel with each other, simultaneously reacting to and co-constructing their own environment" (p. 3). The media event—a concert—unfolded in real time at the venue, yet fans remediated the event in alphabetic text on Twitter, in photographs on Instagram or Twitpic, in video posted online in the hours after the concert, in statistics updated on wikis, and in reviews published online and in print the following morning. New media writing technologies in the hands of fans afforded the transformation of a single concert into a collaboratively composed transmedia story situated within individual fan and Springsteen concert histories.

Consider the following tweet, which is a retweet of an original tweet that contains several of the Springsteen fan practices I have discussed. The retweet was published via the social network management site Hootsuite; the original tweet via Tweetdeck:

Example Corpus Tweet

RT @backstreetsmag: E Rutherford Night 2 report up now, @AMSadler photos to come http://t.co/cpRtYiJz #springsteen #WBNJ2

Breaking down the tweet piece by piece reveals its complexity. First, it is a retweet, which I have labeled tummeling because it “facilitat[es] conversation and engagement within online communities” (McNely, 2010, p. 4). Retweets are emergent texts within the Twitter network; there would be no retweet if the original tweet didn't exist. So, we presume the author of the retweet was either following the user who composed the tweet (in this case, @backstreetsmag, the Twitter account for Backstreets Springsteen fan magazine) or following one or both of the two hashtags included in the original tweet or searching for tweets containing any of the words in the original tweet. We also presume the author thought the content of the original would be of interest to her followers. The act of composing a retweet shows an awareness of her social network and how shared texts can enhance the quality of that network.

Second, we look to the author of the original tweet: Backstreets fan magazine, which is now the most popular and longest running Springsteen fan magazine. The glossy-covered and professionally laid out print version appears approximately once a year, but it maintains a significant web presence with daily updates about Springsteen. In this tweet, the magazine was reporting a link to a review of the April 4, 2012 concert. The review and the tweet about the review are emergent texts.

Third, in the tweet Backstreets mentioned a popular Springsteen photographer through a process I have labeled notifying: "A tweet using an @mention not necessarily to have a conversation but to alert someone that they have been mentioned." Here, however, the @mention was not only to alert the photographer. Rather, it was to give rhetorical weight to the content of the review. The tweet was an argument: click on this link because a famous Springsteen photographer's images will be included, making the review even more special. It also signaled that the review will be multimodal, containing alphabetic and photographic text, both of which were composed in response to the concert event. The use of the photographer's name was intertextual because the author assumed his followers would recognize not only who the photographer was but the quality of the photographs.

Fourth, the original author engaged in a process of mediating by including a link to the review. The author understood Twitter as a writing space that facilitates information distribution through the use of hyperlinks. The tweet and the URL emerged after the author composed and published the review online using various information technologies.

Fifth, the original author included two hashtags in an attempt to affiliate with other Springsteen fans. Both choices were apt, as the #springsteen hashtag would reach those who are interested in Springsteen and the #wbnj2 hashtag (the hashtag for the April 4, 2012 concert) had the potential to reach those who were interested in the concert. By using hashtags, the author showed an awareness of the larger Springsteen fan community, its Twitter-centric discourses, and how to use Twitter's composing structures to compose a more sophisticated tweet.

This one retweet reveals a complex system of texts (concert, fanzine, review, web site, photograph, tweet), technologies (Twitter, Twitter functionalities, Hootsuite, Tweetdeck, web design, camera), and human actions (network awareness and composing photographs, reviews, tweets, retweets) that afford the ability for fans to practice their fandom in direct response to a media event. Etienne Wenger (1988) has suggested:

Our engagement in practice may have patterns, but it is the production of such patterns that gives rise to an experience of meaning. . . . All that we do and say may refer to what has been done and said in the past, and yet we produce again a new situation, an impression, an experience: we produce meanings that extend, redirect, dismiss, reinterpret, modify or confirm—in a word, negotiate anew—the histories of meanings in which they are part. In this sense, living a constant process of negotiation of meaning. (pp. 52–53)

In communities of practice, individuals consistently engage through various discourses and practices in an attempt to create meaning from their experiences. The patterns Wenger described map on to the rituals fans have (such as singing the first verse of "Hungry Heart") and expect to experience at a concert (such as Springsteen crowd surfing back to the stage). When fans tweet their expectations and experiences they perpetuate community practices, which, in turn aids in the creation of meaning—in other words, "the construction of personal identity" (Cavicchi, 1988, p. 137).

The tweets analyzed in the Izod Center corpus are nuanced compositions. The authors—the fans—are sophisticated writers who reify the practices of historicization, integration, intertextuality, mediation, and perpetuation. That is, an awareness of their own history as fans and of Springsteen-related texts; an understanding of the Springsteen fan discourses and how to apply them; a desire to create transmediated texts about the concert; and the ability to add to new writings to the community.

Grounded theory studies have the potential to continue to transform how scholars, teachers, students, and the general public understand the community-wide importance of composing, even especially in 140-character bursts. Such studies have the potential to continue to erode the notion that all important or necessary or valuable writing emerges in a classroom or in response to a prompt. Assignments informed by this kind of work have the potential to give students the opportunity to use grounded theory methods to engage with communities outside the classroom, thus learning more about community spaces, texts, and discourses, and how members of the community are using new media technologies to compose. By looking to fan communities that compose so prolifically and in so many on- and off-line spaces, like the Springsteen fan community, we as a field have the opportunity to broaden our understanding of the distributed nature of writing and consider how and why, as Kathleen Blake Yancey (2004) wondered aloud, people are writing so often and in so many spaces when no one is asking them to.

Track 10: Perpetuating

Track 12: References