Since the inception of new media and its offspring, social media, individuals and groups with a mind toward political, social, and cultural change have debated the merits of this new digital form of activism. With critics coining terms such as “clicktivism” and “slacktivism,” it’s clear to see that digital activism isn’t nearly as universally valued as is direct action or boots-on-the-ground (BoTG) activism.

Is this because of a generational divide between activists, with younger people seemingly willing to accept engagement in online forums as valuable, while older generations do not? Or, is it because the value of activism is measured exclusively by the end result: change? If we are using change as a metric, can’t nearly any form of activism be labeled a success—or failure—depending on who is assessing? I would argue that acquisition of new information is a change in educational status, that adoption of a position is a change in heart and mind, that asking friends and followers to care about something you care about is a change in degree of engagement. And, what if asking them to care drives them to actually do something?

The reality is that the Internet is changing the way we do business in all areas of our lives. We are shopping, working, socializing, and even finding love interests in the online world. In 2013, for example, U.S. retailers saw a 50% decline in traffic to their brick and mortar stores during the holiday shopping season and a 10% increase in their already robust online traffic (Walker, 2014). In the dating world, 38% of those currently “single and looking for a partner” have used an online dating site (Smith & Duggan, 2013). Twenty-three percent of online daters say they have found a long term relationship or marriage through a digitally mediated space like a dating site (Smith & Duggan, 2013). The Internet exposes the limitless options we seem to have. Consumers are using the Internet to make more informed buying decisions, and businesses use the Internet and social networking systems to both market products and services and elicit feedback from their customers. Fifty-seven percent of ads shown during the 2014 Super Bowl, for example, displayed an associated hashtag, reflecting an intent to drive customers to interact with a company via social media; this was a 50% increase from the use of hashtags in the 2013 Super Bowl commercials (Sullivan, 2014). The dramatic increase in activity in the online world signifies awareness of the convenience, effectiveness, and efficiency of doing some things online instead of offline.

The participatory nature of Web 2.0 has also marked an interesting evolution in engagement and activism. Because of access, convenience, and simplicity of use, the digital realm invites participation from those who might not otherwise be compelled—or able—to participate in person.

Several recent studies from the Pew Internet and American Life Project—“Social Media and Political Engagement” (Rainie, Smith, Schlozman, Brady, & Verba, 2012), “Civic Engagement in the Digital Age,” (Smith, 2014), and “Who’s Not Online and Why,” (Zickuhr, 2013)—demonstrated both interest and technological opportunity to engage in cybercitizenship1 activities.

The Pew surveys on engagement noted that social networking service (SNS) users do see social media as a suitable forum for engaging in the public sphere. In fact, Pew found that 39% of all American adults have already used social media for civic or political purposes (Rainie et al., 2012). Since 86% of adult Americans use the Internet, 73% of those are SNS users, and 56% of American adults now have a smartphone, it’s apparent that there is opportunity for engagement using these tools that are already so highly integrated into the lives of adults in this country (Zickuhr, 2013).

I recently conducted an informal survey of my own Twitter followers hoping to determine their attitudes toward social media as a forum for civic and political engagement. The findings of my survey amplify those of the Pew engagement surveys, ultimately pointing to both desire and opportunity, an atmosphere ripe for digital activism. Here are some of the findings:

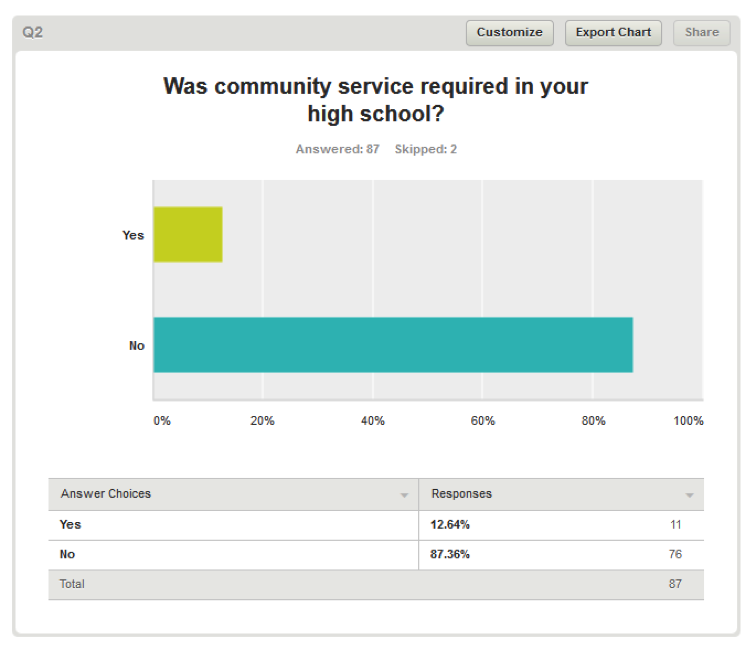

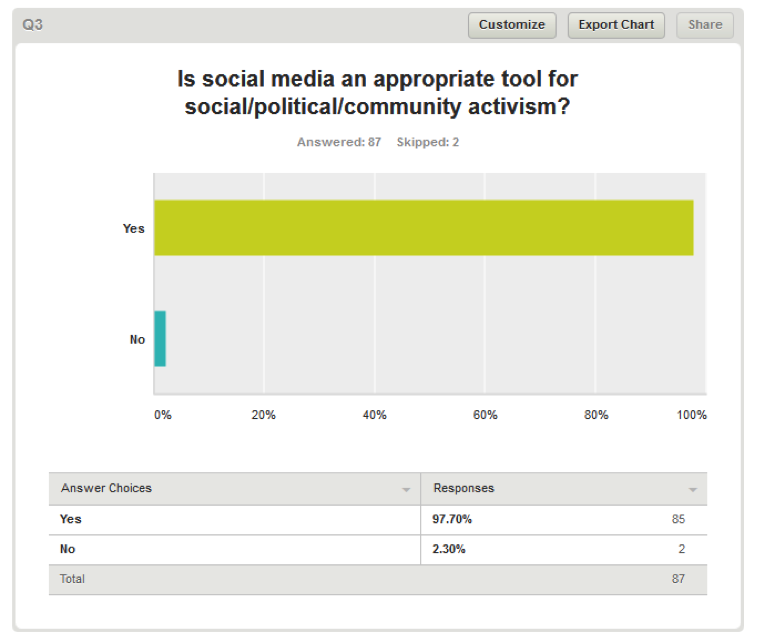

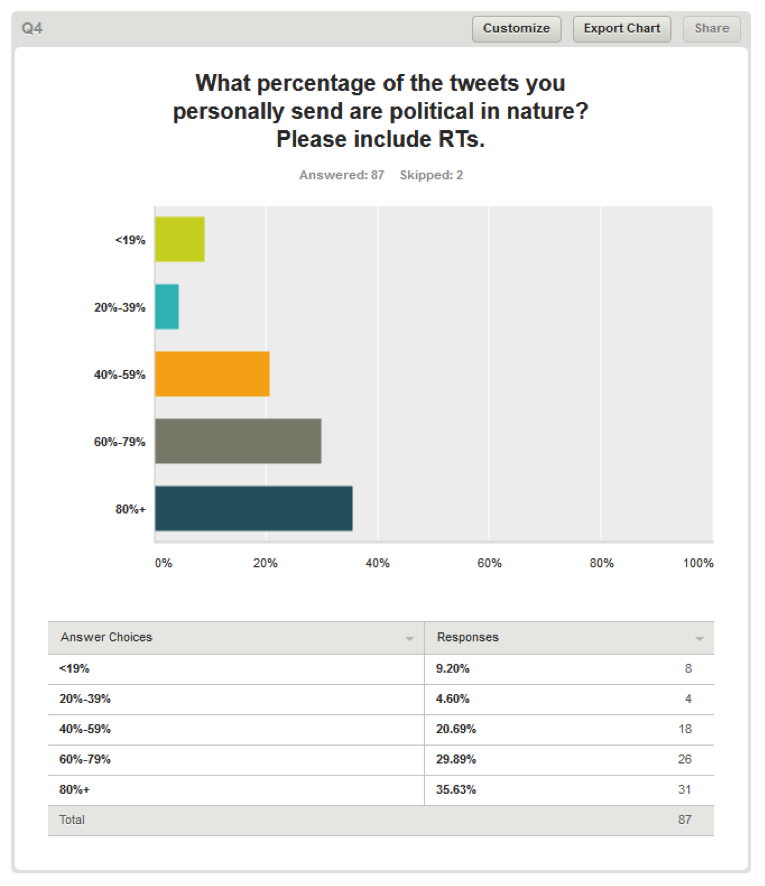

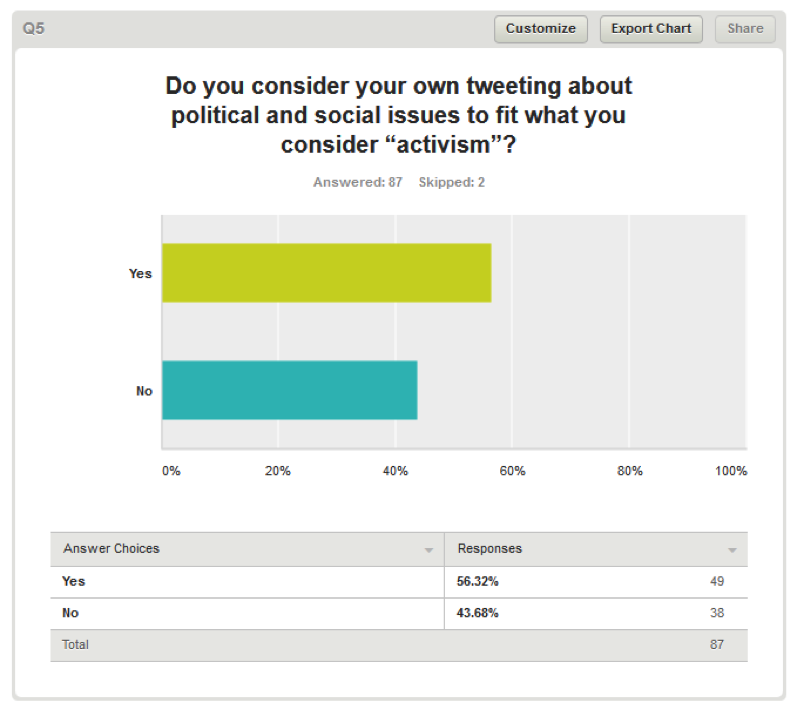

There were 87 responses to the survey with ages ranging from 17-70, and while all respondents were already active SNS users, it is safe to say that their lived experiences with education, activism, and social media are quite diverse. Through this brief survey, I discovered that community service had been required in high school for 87% of the respondents. While a shocking majority (97%) viewed social media as an appropriate tool for social/political/community activism, and 35% of respondents said that 80% or more of their tweets and retweets were political in nature, only a little more than half of those surveyed said they considered such tweeting on issues to fit what they considered activism. This is an interesting piece of information, particularly since so many qualified social media as a tool for activism. This reluctance to identify their political engagement online as activism could reflect an outdated definition of activism or an awareness of the limitations of the proverbial echo chamber or it could simply be a reaction to the public perception of social media activism or advocacy as slacktivism.

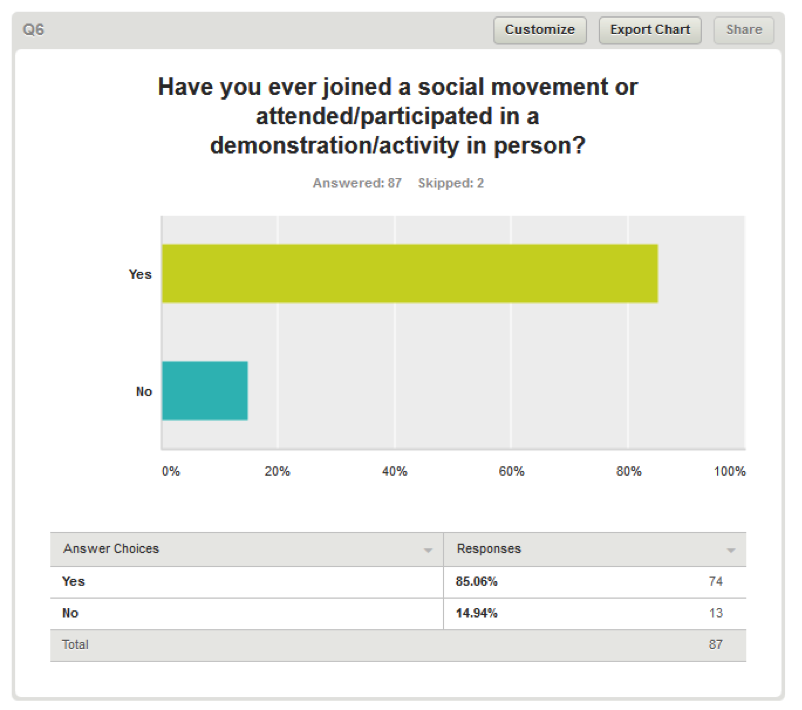

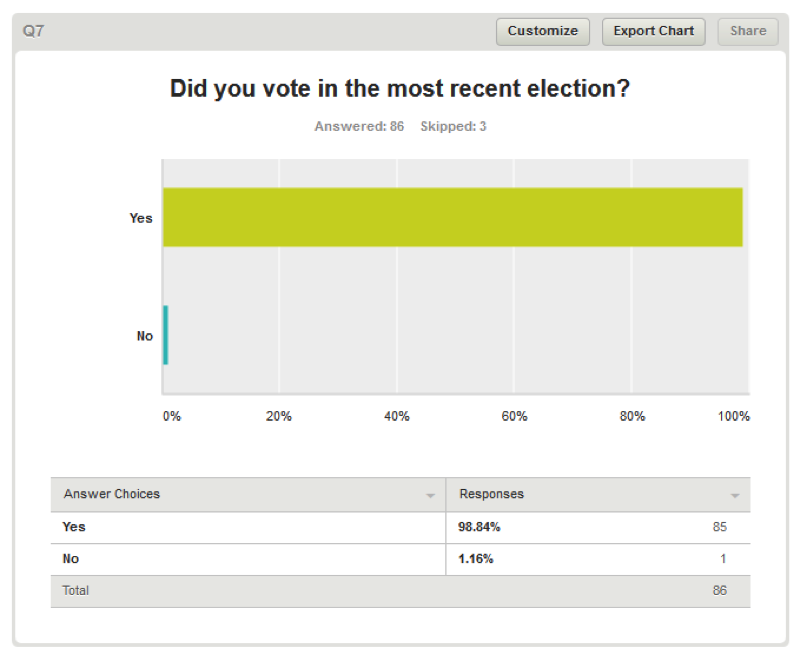

The reason for the discrepancy between what the respondents are actually doing and what they call it is something I would like to understand further, particularly in light of the fact that 85% of respondents also said they have joined a social movement or attended a demonstration in person, and 98% said they voted in the most recent election (the one who didn’t vote was not yet legally eligible), so they are obviously a civically and politically motivated group. These findings certainly aren’t scientific, but I think they tell a story that is being largely overlooked by critics of social media activism. The desire and willingness is out there. The work is being done. The forum is valued by those who are doing the work. But there is a disconnect in labeling the work as activism.

This discrepancy presents tremendous opportunity for those who teach rhetoric and composition, civic engagement and service learning, community literacy and public writing, even technical communication. We are in a position to shape understanding, perception, agency, and efficacy surrounding the use of public rhetoric, and we should not ignore the digital as a means to accomplish those goals. One way to overcome this potential obstacle in labeling online action as activism could be for pedagogues to expand their civic, public, and new media writing lessons to include digital civic engagement.

While we might not ever see digital activism replace BoTG efforts, any more than we might see online dating replace meeting a romantic prospect in an offline public space (a meatspace), there is no doubt that Internet and mobile technology are changing the face of activism.2 Whether these tools are harnessed for messaging or mobilization of traditional BoTG activism, the reality is that digital and digitally-enhanced activism are here to stay.

The *New* Public Sphere

The *New* Public SphereThere is a long history of civic rhetoric in the public forum. Aristotle, Quintilian, and Cicero all devoted their lives to development of the art and skill of rhetoric, and all worked toward a civic end. But it isn’t until Hortensia’s “Speech to the Triumvirs” in 42 BC where we can begin to see lines drawn—and simultaneously blurred—between rhetoric and activism, public and counterpublic speech, where true power dynamics are disrupted in a public space, and where dissident actions can lead to change.

In response to a proposed tax against the property of wealthy Roman women (which was ultimately taxation without representation, since women could neither serve as senators nor debate in the Forum), Hortensia marched in protest into the public space where women were forbidden. There she delivered a brief but poignant speech, effectively ending the tax for two-thirds of those affected. The effectiveness of Hortensia’s speech could be attributed to her training in rhetoric—she was the daughter of the great Roman orator Quintus Hortensius—or her boldness in challenging the Triumvirate, or her presence in a space not open to women. In reality, it was probably a combination of the three.

Hortensia never intended to be an orator or an activist. She delivered the famed speech only because “no man would dare offer the wealthy matrons legal aid” (Osgood, 2006, p. 542). Nevertheless, her move emboldened other women more than 150 years later who once again gathered in the Forum to protest the Oppian Law, a law that controlled the amount of jewelry women could own and wear in public. Though in this case there were many noblemen in support of its repeal, it wasn’t until the rebellious women blockaded the path to the Forum and began to boldly address consuls and magistrates directly that change began to happen. The growing support for the cause—and subsequent expanding crowd—emboldened the protestors who showed up every day until the law was eventually repealed.

In both of these cases, the protests proved fruitful: Taxes on wealthy women were reduced and the Oppian Law repealed. However, even if the public rhetoric had served only to educate others of an inequity or suppression of rights or challenge the existing power structure, we would probably all agree it would still have been activism.

Dissident behavior such as that of Hortensia and the Oppian Law protestors is often necessary in order for any degree of change to occur, and there is an equally long and fascinating history of dissident efforts in this world. In the age of digital activism, it’s important to recognize the parallels between social media and its revolutionary predecessors like dissident presses, street papers, ‘zines, or alternative media like that of Situationism or Dadaism3. If social media is examined closely, it becomes clear that the kind of activism conducted digitally encompasses many of the already valued face-to-face forms of activism.

Where street papers and ‘zines have long served as a vehicle for expression of ideas and individuals who do not fit neatly into a dominant place in mainstream society, online spaces continue to provide an opening and a medium for the establishment of such “counterpublics” (Asen, 2000; Hauser, 1998; Warner, 2005). Social media certainly fits many of the criteria for “public” outlined by Michael Warner (2005) in Publics and Counterpublics, which include that a public is 1) "self-organized," 2) "a relation among strangers," 3) "the address of public speech is both personal and impersonal," 4) "constituted through mere attention," 5) "the social space created by the reflexive circulation of discourse," 6) "a group that acts historically according to the temporality of their circulation," and 7) "poetic world making" (pp. 67-118).

Since social media provide opportunity for those groups who don’t necessarily fit the “dominant culture” or are not recognized in mainstream to discourse and message, they have become a purveyor of “counterpublics” (Warner, 2005, p. 113). An excellent example of this idea of counterpublic in the social media realm is the subaltern Twitter group GOProud, a politically conservative arm of the Republican Party that is openly gay. They have been all but ignored by the party elites and were even disinvited from the 2013 Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC), yet they have benefitted from the tools of the 21st century to unite and work toward a shared common interest. In addition to providing opportunity for individuals with shared interests to connect, the digital world provides the means for such individuals to cultivate their ideas and message in a way that might previously have been cost- or politically-prohibitive.

Social media forums—discussion boards, Facebook, Twitter, Volkalize, Blogger and Wordpress—offer community building and networking opportunities, prompting the establishment of new publics. They have become something of a blend between the Habermasian salon (a space where individuals converge to discuss and debate issues of a civic, community, or political nature) and Gerard A. Hauser’s (1998) public sphere, a “discursive space in which individuals and groups associate to discuss matters of mutual interest, and, where possible, to reach a common judgment about them” (p. 21).

The new public sphere serves not only the interests of counterpublics, however. There are many ways that mainstream causes benefit from the reach of social media. Consider the Armyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) Association’s Ice Bucket Challenge that went viral on multiple social media platforms in 2014 and raised not only awareness but millions of dollars for the organization that works to cure Lou Gehrig’s Disease. The peer-initiated challenge was to dump a bucket of ice water on your head within 24 hours of receiving the challenge or donate $100 to ALS. Many who received the challenge did both. More interesting is that this movement united celebrities, ordinary citizens, politicians, athletes, and sufferers of ALS almost instantaneously. According to a press release issued on August 29, 2014 (just 30 days after the challenge began), ALS had raised over $100 million for research and procured 300 million first-time donors (ALS Association, 2014).

Because of the highly interactive nature of online spaces, digital activism allows for vastly creative forms of rhetoric (both visual and sonic) that could not be accomplished simultaneously in print media or underground radio prior to the existence of Web 2.0. Add to this the massive distribution and circulation capabilities of online activism (through “liking” and “sharing” and “retweeting” activist messages), and it becomes clear why this new digitally mediated space is one with tremendous potential for outreach, education, and influence—indeed, social change.

Perhaps most valuable is that digital media, unlike its alternative and activist media predecessors, effectively disrupts the existing power dynamics in politics and media, making it an ideal situation for activists to do their work. This shift in dynamic puts the power in the hands of the user as one who transmits and circulates at her will, on her timeframe, and to the extent she desires. It levels the playing field to some degree, and it provides opportunity for voices to be heard that might otherwise be ignored by those holding the reigns in politics and media.

Engagement: It's Trending

Engagement: It's TrendingDespite the message of the mainstream media, a message of disengagement that is also argued in Robert Putnam’s (2000) oft-referenced book Bowling Alone, and a body of pre-2008 research that shows civic engagement in young adults declining, more recent research shows a different message: Civic engagement among young people is actually on the rise.

The website DoSomething.org, which touts itself as “one of the largest orgs for young people and social change” has 3+ million members working to “make the world suck less.” It specifically targets U.S. and Canadian citizens under the age of 26 (affectionately calling the 26+ crowd “old people”) and provides opportunities for users to serve on issues they care about, on their schedule, to whatever degree they want. It’s basically action tailored to activists’ lives. In fact, in a 2012 study, DoSomething.org found that a whopping 93% of young people want to volunteer. The study also showed that the more social a young person is, the more likely s/he is to engage in social action. And the primary factor in whether or not a college student engages civically? Friends (“The DoSomething.org Index,” 2012).

The findings of the DoSomething.org study tell us that the key to getting more young people engaged in social and political action is to make it, well, more social. This is where social media comes in, and this is where teachers of rhetoric and composition have an opportunity to shape engagement and citizenship through the kinds of new media lessons we teach.

Beyond the numerical data, a host of qualitative data from focus groups with young adults exposes some common trends in propensity toward civic and community engagement. The information gained in these studies can help us identify opportunities to impact engagement in a variety of ways we might not have previously considered. In those areas where young adults are disengaged, great opportunity exists.Italian scholar Giovanna Mascheroni (2012) studied young people’s attitudes towards civic and political engagement through peer group conversations. She wanted to understand how young people used social networking services (SNSs) as a means to engage. For the most part, her empirical evidence showed that young people who were already engaged in some way—or whose parents had made political conversation part of the family culture—were part of a “civic culture” and therefore politically interested or engaged, despite sometimes feeling jaded about how much influence they would actually have on problems facing their community (Mascheroni, 2012, pp. 211-12). However, young people who came from lower-income families and/or those families that did not discuss politics and social issues were part of an “uncivic culture” (Mascheroni, 2012, pp. 211) and were predictably disengaged or disaffected with politics.

This probably seems like common sense: If parents discuss political, social, and cultural issues at the dinner table, for example, children will grow to be more civically literate, thus, engaged (Mascheroni, 2012). However, because not all young people come to college with these requisite skills and experiences, the responsibility rests on educators to teach them.

Recent work out of The Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE) at Tufts University shows that young people who are asked to engage (say, by a community leader, in a college class, or by a friend) tend to stay engaged civically (“That’s Not Democracy,” 2012). This engagement can be as simple as joining an ongoing conversation about community problems, much like the work Linda Flower (2008) has done in the Community Literacy Center, or it can be more active and action-oriented (like serving at a shore sweep or on a Habitat for Humanity project, maybe working on a political campaign).

The goal should always be to have an element of reciprocity in the work being done. That is, the civic activities should be fulfilling to the individual engaging in them as well as the perceived beneficiary of the engagement. Without this element of reciprocity, there is little chance that the engagement experience will have a lasting impact and the desired element of longevity. As many civic pedagogues warn, an imbalance of benefits of service can result in less engagement and deeper strain on existing community relationships than had the service never occurred (Deans, Roswell, & Wurr, 2010).

As educators, we can help students develop their civic mindedness through both asking them to engage in the public sphere and also teaching them how. For example, Mascheroni (2012) noted that young people who “develop complex patterns of news consumption online” and are free to choose “lifestyle-related forms of engagement” (pp. 216-17) will engage more in what Bennett called “social movement citizenship” (as cited in Mascheroni, 2012, p. 217). As compositionists, we can provide both instruction and opportunity to develop meaningful, informed, and effective civic participation. Finally, introducing social media into our classes—and linking that tool to social or political action—can be just the right formula for prompting many more of those 93% who want to engage to actually take the steps to do something.

From Digital Technology to Digital Action: Charting New Territory

From Digital Technology to Digital Action: Charting New TerritoryA recent study from the University of Washington (UW) analyzed nearly 1,200 digital campaigns from more than 150 countries that have occurred since 1982, with the greatest emphasis on campaigns since 2008. Co-founder of the Digital Activism Research Project (DARP) at UW and manager of this project, Mary Joyce set out to identify the impact of digital technology on civic engagement. She and her research team have worked to compile a database of digital activist campaigns for activists, scholars, and journalists who wish to study them further.

Stated goals of the project include efforts to “raise the level of foreign policy expertise with the evolving dynamics of international relations in a digital era” and to “improve public understanding of the potential and pitfalls of civic engagement using digital media” (Joyce, Howard, & Rosas, 2013, para. 4). Additionally, the DARP project team speaks to the controversy surrounding the value of digital activism in the “Project Contribution” section of the website:

This project is unique, and pioneering research into digital media, civic engagement, and non-violent conflict. There are some scholarly efforts at tracking civic activism that arises online-only. But our contention is that the distinction between online and offline politics is no longer meaningful, that contemporary international relations and non-violent conflict increasingly has causes or consequences in digital media. And unlike other scholarly research efforts, we believe we must have a deliberate dissemination strategy to reach out to policy makers. (Joyce, Howard, & Rosas, 2013).

The Global Digital Activism Data Set (GDADS) is the result of the digital activism campaigns that were analyzed (Joyce, Howard, & Rosas, 2013). These results have been coded into a spreadsheet based on several key criteria: initiator of action, target of action (the one the initiator hopes to influence), type of digital medium used (website, blog, social networking service [SNS], e-petition, etc.), and purpose of action. The campaigns are further categorized based on their online or offline activity—which helps to discern whether the campaign was exclusively digital or digitally enhanced—and the duration of the entire campaign.

Joyce, Howard, and Rosas (2013) classified four major types of “causes advanced or defended in digital action”4 (pp. 34-35):

as well as several key purposes behind digital activist work, including bypass, synthesis, resource transfer, co-creation, mobilization, broadcast, network-building, and technical violence5(pp. 27-29).

Studying types and locations of digital action can help identify successes and failures, as well as additional opportunities for training and skills development. For example, through their analysis of these campaigns, the team of researchers discovered that the primary form of digital activism in Europe and Asia is video (YouTube), while North Americans rely heavily on e-petitions as their dominant form of digital activism (Joyce, Howard, & Rosas, 2013). This could signal among Americans a deficiency in digital literacy skills, that is, a lack of skills necessary to build effective video messaging. Or it could signal a preference among Americans to petition their leaders to make change, possibly reflecting the degree of influence Americans have historically had in using a collective voice to influence change. Either way, it presents an opportunity for educators and parents alike to both value and develop civic and digital literacy skills in young people whose futures we are helping to shape.

Perhaps the most interesting finding of the UW study was that the most effective digital activist work is that which is combined with boots-on-the-ground (BoTG) work, a hybridization of activist efforts. The hybridization is best illustrated in mobilization efforts, where social media is used to supplement BoTG efforts, to communicate either a call-to-action or the logistics of a specific event. While this hybridization might not be essential in digital activist work in the future, as tools and technological capabilities continue to expand, it seems to serve both the image and impact of activism for now.

Much like Saul Alinsky’s contributions to community organizing, the DARP work serves to help digital activists and those shaping policy in the 21st century understand how individuals, communities, and entire citizenries can be engaged and impacted through digital media. It provides activists with prototypes for effective activism that help establish protocols for future activist campaigns. Because DARP draws no meaningful distinction between digital and BoTG as far as calling the efforts “activism,” and because the work of that project team is linked to political scientist Gene Sharp, the scholarship they are producing further validates online or social media activists.

Slacktivism (Otherwise Known as Clicktivism)

Slacktivism (Otherwise Known as Clicktivism)It is understandable why radical activists might reject, on first glance, the kinds of engagement conducted online: signing of petitions on Change.org, liking or sharing cause or issue information, hashtagging or retweeting commentary on Twitter. These activities seem to require little investment on the part of the person clicking to spread the word. It might even seem challenging to identify the reciprocity in such activities. However, when we consider the ways in which social media has furthered recent social and political causes, such as Il Popolo Viola and the Arab Spring, particularly in countries where the media is controlled by the government, the value of mass electronic dissemination and circulation becomes apparent. In fact, digital activism looks a lot like its offline counterpart in efforts to impact social change.

While some activist researchers give digital activism a lukewarm reception, acknowledging the benefits of it and the positive impact digital technology has on an individual’s likelihood to participate (Boulianne, 2009; Breuer & Farooq, 2012; Joyce, Howard, & Rosas, 2012), others are fierce critics. Rustin Klafka (2010) said clicktivists are simply clicking to make themselves feel better, while not really caring about the cause because they aren’t taking pains to do any real work associated with change (as cited in Breuer & Farooq, 2012, p. 4). Sam Biddle (2012), author of the blog post “Twitter Doesn’t Make You Martin Luther King,” went so far as to say most digital activists are “fakers, half-assed retweet activists, who ‘support’ Iranian dissent or ‘raise awareness’ about homophobia with the same zeal that we click Like on a video of two cute cats playing with an alligator” (as cited in Breuer & Farooq, 2012, p. 4). Consider also the position of public scholar Malcolm Gladwell, who penned the 2010 The New Yorker piece “Small Change: Why the Revolution Will Not be Tweeted,” in which he argued that “social media can’t provide what social change has always required.”

But there is new research showing online social networks do actually influence political expression and behavior. Anita Breuer and Bilal Farooq (2012) surveyed participants in the Ficha Limpa activist campaign against corruption in Brazil in an effort to better understand online and offline behaviors. Though they found that “low-effort online activities” such as social networking service activities “contribute[d] little to increase[d] political participation” (Breuer & Farooq, 2012, p. 2), they did acknowledge that “targeted campaigning by e-advocacy groups has the potential to increase the political engagement of individuals with low levels of political interest and can help to produce the switch from online to offline participation among individuals with high levels of political interest” (Breuer & Farooq, 2012, p. 1). Like the findings from Joyce, Howard, and Rosas (2012), Breuer & Farooq (2012) noted that digital media effectively supplements the activities of those who are already interested or engaged in politics.

Shelley Boulianne's (2009) analysis of the impact of the Internet on engagement acknowledged a positive impact but claimed the impact is quite modest. This study must be weighed in context, though. It analyzed activity from 1995-2005, making the data more than a decade old, so it could hardly take into consideration the activity on social media since the advent of Web 2.0. Additionally, because of the speed at which technology is advancing and evolving, academic work surrounding digital technology is virtually obsolete by the time it’s published. Users adapt and find ways to do online the same kinds of things they were doing offline before, and this reality is even truer in 2015 than 2005.

In fact, the Boulianne (2009) study barely covers the time period of Howard Dean’s Blog for America and misses altogether Obama’s Text Out the Vote campaign, which are considered some of the earliest uber-successful political activism campaigns using new media. Since then, there are too many movements/campaigns to count, but over 1,200 notable, according to the Digital Activism Research Project (Joyce, Howard, & Rosas, 2012).

A more recent and extensive study on political mobilization through online social networks shows tangible results of an online get-out-the-vote type campaign. Researchers at the University of California San Diego (Bond et al., 2012) used the midterm Congressional elections of 2010 to conduct an experiment on Facebook users and political activity. They wanted to understand the degree of influence that online messaging about voting had on a user’s “political self-expression, information seeking, and real-world voting behavior” (Bond et al., 2012, p. 295). The experiment involved placing a message on the top of select users’ newsfeeds reminding them of Election Day and inviting them to click on an “I Voted” button to share this status with their friends. One group (the “social message” group) was also shown pictures of their own Facebook friends who had also clicked on the “I Voted” button, while the other group received only the informational message.

The members of the social message group were more likely to participate in political self-expression and information seeking (which was measured by their clicking on a link to learn about their designated polling place) activities, but most importantly, they were more likely to actually vote (Bond et al., 2012). Though the study emphasized that the “social contagion” is most heavily correlated to close Facebook friends, that is, those friendships deemed to be an online reflection of a close face-to-face relationship, the researchers noted that “even weak ties seem to be relevant to its spread” (Bond et al., 2012, p. 297). This finding silences one of the primary arguments of critics such as Gladwell (2010): that the “weak ties” of social media are not sufficiently motivating for action or change. Ultimately, the study drew data from 61 million Facebook users and was matched against public voting records to verify that a vote was indeed cast. The findings illustrate that “online political mobilization works” (Bond et al., 2012, p. 297); in fact, the online influence matches face-to-face influence noted in previous studies, where “each act of voting on average generates an additional three votes as this behavior spreads throughout the [social] network” (Bond et al., 2012, p. 298).

In another example of the social impact of Facebook activism, Stephanie Vie (2014) discussed the widespread transmission of a cause-based logo in her article “In Defense of ‘Slacktivism’: The Human Rights Campaign Facebook Logo as Digital Activism.” Vie (2014) discussed the modified Human Rights Campaign (HRC) logo (the red square with a pink equal sign in the middle) introduced by the HRC in March of 2013 when California was considering Proposition 8, a ban on same-sex marriage. The HRC asked supporters to make the red square logo their profile image in support of the cause of marriage equality. Although there were countless variations of the meme, some expressing support and some opposition, it was shared 189,000 times and had the reach of tens of millions—appearing 18 million times in the Facebook newsfeed (Vie, 2014). Vie (2014) noted that “the Human Rights Campaign logo is an important example of how even seemingly insignificant moves such as adopting or remixing a logo and displaying it online can serve to combat micro–aggressions” and “help draw attention to societal issues and problems and can result in increased feelings of support for marginalized groups" ("Introduction" section, para. 4).

The power of social influence on behavior cannot be dismissed, and in social networking sites especially, we need to have a good understanding of how to harness that power and use it to increase participation in both online and offline activities. It is also worth remembering that objections to online engagement activities (denoting them as lazy activism) don’t take into consideration the effort or time required in—or degree of passion underlying—the efforts of the organizer, the creator of the image or petition being circulated, or the designer of the Facebook fan page. These are community organizers who have taken up a new, highly participatory form of media to influence or affect change. Because they are doing this work on their terms, using their unique skill set and incorporating technologies and devices they are comfortable with, there is a degree of reciprocity that adds personal value to the activist or advocacy work they are doing. It is this personal investment and value that prompts the activists to enlist support of their friends, both online and offline, and, as we saw in the Bond et al. (2012) study, that type of social influence matters. Additionally, these digital activists are able to see the reach of their efforts in ways that boots-on-the-ground (BoTG) activists might not.

As the methods of direct action begin to encompass new technologies, I would call on critics to reconsider their position on slacktivism and perhaps begin to see the value in the kinds of efforts that are being taken online. If we dismiss the notion of feel-good passive activism—which is not unique to the digital age, by the way—and embrace the parallel efforts and expanded circulation afforded in the online world, we might be able to direct our focus to the education of Americans, particularly young Americans, on how to do this digital advocacy work effectively. Whether this change is quantifiable, like an increase in voting activity, or anecdotal, like exposing millions to a message of support for a cause they might not have otherwise vocalized, it is undeniable that social networking is a platform for awareness raising activities, “and raising awareness is a crucial first step toward significant and lasting change in the off-line world” (Vie, 2014).

Hacktivism, or What’s With the Guy Fawkes Mask?

Hacktivism, or What’s With the Guy Fawkes Mask?Hacktivism is perhaps the form of digital activism that receives the greatest media attention. One mention of the word “Anonymous” conjures up the image of anarchist computer geeks all donning Guy Fawkes masks as they hammer away at their computers in dark basements working diligently to disrupt the online world. This is the image of digital activism that has been seared into too many minds, but hacking really consumes a very small portion of digital action being taken to affect social or political change (Joyce, Howard, & Rosas, 2012), and despite the parallels that are asserted in media and political circles alike, not all hacktivists are akin to cyberterrorists6.

What is hacktivism, anyway? Ultimately, it is a variation of alternative computing, an outgrowth of open source and file sharing software technology, which is used in an antagonistic way to serve a political purpose. In addition to the term cyberterrorism, hacktivism has been linked to such terms as cyber attacking, cyber exploitation, and “digital civil disobedience” (Li, 2013, p. 304).

Hacktivism is not to be confused with illegal hacking activity, like hacking into banks for purposes of theft, which is a more run-of-the-mill cybercrime. Instead, hacktivism is “politically-motivated hacking” that is largely anti-institutional in nature (Warnick & Heineman, 2012, p. 112). It is digital radicalism, particularly when it takes on an anti-war, anti-military flair. Hacktivism is radicalism that is disruptive of ordinary routines or business practices, predominantly within the government. It might be comparable to rallies, sit-ins, or occupation of a government building or establishment (consider traditional radical protests, like Occupy Wall Street). It could be "unauthorized intrusions" (Warnick & Heineman, 2012, p. 121), total website takedown, or website graffiti (such as the defacing of governmental sites like the U.S. Department of Justice and Central Intelligence Agency sites in August and September of 1996). Like cyberterrorists, “hacktivists pursue political goals, but their activity does not correspond quantitatively or qualitatively with the possible outcome of cyberterrorist acts” (Stanley, 2010).

Though hacking activity is discussed repeatedly in the mainstream media, only 2% of activist campaigns looked at in the Digital Activism Research Project (DARP) global digital activism study were found to use hacking “with destructive or disruptive intent” (Joyce, Howard, & Rosas, 2012). Even though hackers who use their digital skills to protest through disruption in the online world are a nuisance, sometimes a very costly one, they are deemed “cyberterrorists” almost exclusively when the target of their work is a government entity.

The Department for Homeland Security defines cyberterrorism as “a criminal act perpetrated through computers resulting in violence, death and/or destruction, and creating terror for the purpose of coercing a government to change its policies.” Despite being compared to al-Qaeda in organizational structure (Warnick & Heineman, 2012, p. 126) and in being present yet simultaneously invisible (the "binary of presence-absence,” [Warnick & Heineman, 2012, p. 133]), Anonymous, who was responsible for hacking Sony, is more an example of theft of intellectual property than cyberterrorism. Yet, because much of their activist work is anti-institutional, anti-government in nature, they are watched by the multitude of agencies investigating cyberterrorism in the United States.

Two individuals recently in the news for their aggressive anti-governmental hacking activities are Julian Assange (Wikileaks) and Edward Snowden. Both of these men consider themselves whistleblowers, indeed, hacktivists. However, as individuals who actively work to disclose abuses of power in the U.S. government, they’ve been labeled cyberterrorists and, should they ever return to the U.S., are likely to be prosecuted under the Patriot Act. Many civil liberties minded individuals are vehemently opposed to the Patriot Act, which they see as a governmental tool to virtually silence any opposition. Thanks to the cyberterrorism clause in the Patriot Act, penalties for hacktivism against government sites have increased from one year in prison to 70 years. This shift can be best explained by the post-9/11 "terrorist-centric rhetoric" of the Bush administration (Warnick & Heineman, 2012, p. 129).

The malicious reformulation of the term “hacktivist,” what Peter Ludlow (2013) calls “lexical warfare” is perpetuated by government entities, yes, but also by private security firms, in whose interest it is to “manufacture a threat” (Ludlow, 2013). The motivations of these two groups, groups that stand to gain most by silencing all hacktivist efforts, should be suspect.

The primary goal of hacktivists is to affect social change (Ludlow, 2013). Digital technology is the medium by which these protests are enacted. In order to ensure the validity of such digital activism, there are efforts both social and legal to have hacktivism recognized as falling within the purview of First Amendment coverage. As Xiang Li (2013) noted in her article “Hacktivism and the First Amendment: Drawing the Line Between Cyber Protests and Crime,” the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA) avoids a “categorical prohibition on all forms of hacktivism” specifically recognizing that there are/may one day be viable forms of digital protest that will need the protection of the First Amendment (p. 304). Problematic in the CFAA, however, is that it defines a class of computer systems as “protected”: those belonging to financial institutions (which few would argue with) and the government. Therein lies the problem for an activist; the limitation that protects government computer systems essentially makes it impossible to challenge the authority of the most powerful body in the United States through dissident digital protest. The effect of this limitation runs counter to the concept of civil disobedience, what Civil Rights era Judge Frank Johnson described as a “procedure for challenging a law or policy” (qtd. in Schmidt, 2010, p. 778), the very disobedience illustrated by the sit-ins of the 60s.

To secure protection for what’s known as "distributed denial-of-service" (DDoS) attacks, or server take-downs, Anonymous petitioned the White House in January of 2013 to recognize DDoS attacks as a legitimate and legal form of protest. The organization classified their DDoS work as a virtual sit-in, claiming it to be “no different than any ‘occupy’ protest. Instead of a group of people standing outside a building to occupy the area, they are having their computer occupy a website to slow (or deny) service of that particular website for a short time” (Masnick, 2013).

The criminal liability comes into play when deciding whether or not the hacktivist work is destructive or just disruptive, as well as whether or not the point of protest is on the “property” of the target. The particulars of the discussion surround what constitutes private property (an actual website, the server, the content on the site) and public forum (messages of protest in pop-up windows launched when a user comes to the target website), which are further analyzed in Li’s (2013) article. Again, the debate here can return to a very basic question: who owns the property of the government? Ultimately, the conversation is evolving as the potential of digital protestation is being further realized.

To be clear, cybercrime should be punished, just as any other crime. However, we cannot conflate the terms cybercrime, cyberterrorism, and cyberactivism. There is no denying that public perception influences legislation and public policy, so advocates for hacktivism are hard at work trying to stay ahead of the curve, to ensure their voices and efforts will not be silenced by policy and propaganda that equates all anti-institutional hacktivist efforts to cyberterrorism.

Despite what the government entities warn, it could be debated that there is a purpose and a place for hacktivism, and the method shouldn’t be entirely dismissed as unworthy or annoying. Instead, we might embrace hacktivism as one of the many available tools of resistance, particularly when the object of resistance is the government. Hacktivism provides unique opportunity to advocate a valuable anti-institutional position. It is a strategy that exists to check power, acknowledge imbalances, and demand restoration of balance in power when necessary.

Clearly there is reason to value radicalism and rebellion, which have proven effective at some points in history, and we should also challenge the governmental and mainstream media criticism of such hacktivists (as well as the inappropriate parallels drawn to cyberterrorism). We must think critically about the type of information hacktivists are providing as a result of their digital action as well as the rhetorical value of hacktivism in a digital world.

Civil Resistance: Digital as a Non-Violent Alternative

Civil Resistance: Digital as a Non-Violent AlternativeThe efforts of digital activists can be linked to traditional nonviolent protests and civil resistance activities. Gene Sharp, political science professor and Nobel Peace Prize winner, has written extensively on nonviolent protest movements, particularly anti-government resistance movements, as a means to affect change. Sharp (2005) talked in his book Waging Nonviolent Struggle: 20th Century Practice and 21st Century Potential about the potential of nonviolent efforts in the digital world.

In 2012, researchers Patrick Meier and Mary Joyce began updating Sharp’s 198 Nonviolent Methods chart (originally created in 1973) to serve the digital activist ("Civil Resistance 2.0," 2014). Ultimately, Meier and Joyce’s crowd-sourced database, "Civil Resistance 2.0 ," includes digital and technology-enhanced means of resistance. They recommend digital tools be used in “Protest and Persuasion” type of resistance, which is the kind of engagement we might ask our own social media savvy students to participate in as a gateway to civic engagement.

Some of the methods of using social media for straight digital or digitally-enhanced boots-on-the-ground (BoTG) activism include:

These above methods are also identified in the Civil Resistance 2.0 database as “10 New Methods.” There are other methods of digital or digitally-enhanced engagement beyond those listed above in that they rely on media, rhetoric, or behavior that is limited to new media and social media.

Chances are good that young adults are familiar with some of the items on the above lists. Maybe they see them as entertainment, maybe they’ve even participated in some of them, and maybe they don’t know what to call this activity or how it can translate to meaningful participation in the social and political realm. That’s where teachers of writing and rhetoric can step in.

In my own composition classes, where digital advocacy is a primary focus, we choose semester-long topics (a cause or issue) and engage on three new media fronts: Twitter, Wordpress, and YouTube. We talk about and look at case studies of many of the methods and strategies outlined above, and students acquire functional literacy in hashtagging, trolling, meme-ing, and creation of digital advocacy (in the style of Public Service Announcements [PSAs]) video creation. Though we discuss the strategies that might seem more aligned with “activist” efforts—which certainly is an option for students in my courses—because they are still fairly new to engaging civically and politically using new media tools, I focus my efforts on helping them hone their voice as informers and advocates. I’m essentially teaching the traditional “modes” of writing (expository, narrative, analysis, argument, and persuasion), but through a multimodal, multimedia, social lens where audience and purpose take on new meaning for them.

Through discussions of digital and visual rhetoric, as well as lessons on these digital and new media literacies, teachers of writing and rhetoric can help ensure that our students will be effective consumers and producers of meaningful digital materials (that serve a civic purpose) and also function effectively as digital activists using the same tools already employed around the world to affect change.

Citizen Journalism? But . . . but . . . That’s #JustABlogger

Citizen Journalism? But . . . but . . . That’s #JustABloggerInternet users can harness technology to raise awareness of community and political issues that are being ignored by the dominant or mainstream media and launch a resistance effort. These new ways of reporting stories have been called citizen media, participatory journalism, or citizen journalism. Jan Schaffer, executive director of J-Lab: The Institute for Interactive Journalism, noted the grassroots frustration with local newspapers and media outlets failing to cover community news appropriately: “There’s a feeling of, If ‘Big J’ journalists won’t cover our communities, we’ll do it our way” (as cited in Lasica, 2008, p. 25). These “community media” sites, the first of which can be traced back to 2000, stemmed from the same frustration with gaps in mainstream news coverage that conservative writers and journalists argued was going on in the late 90s.

Andrew Breitbart and Matt Drudge, conservatives who turned to the Internet to investigate and break stories that weren’t getting traction in the oft-cited “liberal” mainstream media, might be considered some of the most well-known individual practitioners of citizen journalism. Though both Breitbart and Drudge had a background in professional writing (Breitbart initially helping Ariana Huffington develop HuffPost) and were already actively engaged in journalistic activities, many of which were based online, they inspired an entire movement of average citizens, laypeople, to engage in journalism. These citizens took to the streets to capture on-camera footage of newsworthy stories that they believed were being ignored, overlooked, or inaccurately editorialized by the mainstream news outlets. This activity is what J.D. Lasica (2008) referred to as “random acts of journalism” (p. 26).

The trend of citizens reporting the news grew in popularity around the same time as did blogging, making it even easier for average citizens to get their stories out to the public. With nearly everyone having a cell phone with picture and video capabilities—and little more than Internet access needed to create and post these stories, pictures, and videos to a blog—digital activism took on a new life.

Some political bloggers, such as conservative pundit Michelle Malkin, were able to grow their online readership because they were also recognized TV and news personalities. Others seemed to rely on validation and recognition of the mainstream media, which eventually would come.

This new form of journalism was challenged very quickly by the establishment (“old”) media, with former Washington correspondent with National Public Radio Juan Williams inadvertently becoming the poster child of the anti-blogging position. In a Fox News panel Malkin and Williams sat on together in June of 2012, Williams launched a public attack on the practice of citizen journalism, dismissively telling blogger Michelle Malkin he was “a real reporter, not a blogger out in the blogosphere somewhere” (Hannity, 2012).

The Malkin-Williams exchange propelled a meta-movement of sorts, with activist bloggers taking to Twitter to express their outrage at the journalistic elites like Williams who publicly mocked the practice of blogging. These protestors documented countless examples of citizen journalists exposing government waste, uncovering abuses of power, showing sides of stories that had been missed or downright ignored by their mainstream counterparts. They tweeted their stories on the hashtag #JustABlogger as a way to ban together and form a sort of counterpublic. The community that was forged as a result of the #JustABlogger movement began working together to share one another’s stories, driving massive increases in traffic to conservative and libertarian blogs. Eventually, many of these blogs would come to be validated by mainstream news outlets who began citing them as sources for breaking news.

We also saw a great deal of spontaneous, amateur journalism throughout the peak of the Occupy Wall Street movement, much of which ended up being referenced in mainstream media sources. Today, citizen journalism has brought international attention to major social and political movements, where citizens understood a crisis was brewing and change was desperately needed (e.g., Hurricane Katrina, 2005; Arab Spring, 2009; Voluntad Popular in Venezuela, 2014).

Perhaps we want to teach, as part of our instruction on evaluating and understanding primary and secondary source material, examples of citizen journalism. Though they’ve been popularized by late-night comedians, man-on-the-street interviews are a great way to introduce students to the concept of citizen journalism. It seems that rather than try to debate the value of this or that (digital activism or boots-on-the-ground activism, popular media or citizen media), we should recognize that each has an appropriate role in the conversation, a seat at the table. We should be working to decide how to harness the most powerful tools for the right rhetorical situations and to identify the areas where there is mutual interest and opportunity to collaborate or hybridize efforts. Exposing students to this new and evolving form of journalism is an excellent opportunity for teachers of writing and rhetoric to teach critical reading and critical writing skills. As academics and activist teachers, we are keenly aware of the fine balance of power in our world. Checks and balances are essential, and participatory media is perhaps one of the most effective ways for us to demonstrate how what we do in the classroom translates to meaningful writing in the real world.

#AmTeaching: Civic, Deliberative, and New Media Pedagogy

#AmTeaching: Civic, Deliberative, and New Media PedagogyJeffrey Grabill (2007) referred to our students, those who write with “advanced information communication technologies (ICTs),” as the “civic rhetors of the 21st century” (p. 3). Like Giovanna Mascheroni (2010), Grabill discussed the notion of civic culture. In both cases, the writers seem to be talking about civic and community literacy, awareness of and connectedness to an individual’s civic and community life.

Many of us teach our students about the great classical rhetors (Aristotle, Cicero, Hortensia) and some of us have an awareness of Habermas and Hauser’s conversations on public sphere. What we need to link for our students is this notion of the new public sphere (online) and how it fits in with activism and activist rhetoric in real life (IRL).

For those of us teachers of writing and rhetoric who count increased digital literacy and/or civic literacy among our mission, teaching and learning to value alternative modes of civic engagement should rank high among our academic and curricular objectives. As part of employing this civic and new media pedagogy as a means of increasing digital civic engagement or activism, we must also instruct our students on how to consume digital materials.

Those in the field who currently advocate for a pedagogy that includes multimodality (Kristin L. Arola; Cheryl E. Ball; Jeffrey T. Grabill; Gail E. Hawisher; Mary E. Hocks; Cynthia L. Selfe; Jody Shipka; Anne Frances Wysocki) consider the necessity of teaching the rhetorics of this new, digital literacy. Assignments, instructional units, and entire undergraduate and graduate level courses are being delivered on visual rhetoric, digital rhetoric, and sonic rhetoric. Competency in these skills is necessary in cultivating not only digital citizenship, but also effective creative and critical thinking skills. These skills must be sharp in order for our students to engage smartly in the online world (lest they become sheeples—followers unable to think for themselves—consuming empty messaging without recognizing it as such).

Mascheroni (2010) noted that young people often have widely varying definitions of what constitutes citizenship, and these definitions impact their efficacy and sense of agency when assigning value to their own efforts toward and ideas about engagement (pp. 214-5). This is why it’s of use to teach them to engage where they want, where they are comfortable, entry-level engagement, if you will, to help build self-efficacy and civic, as well as new media, literacy.

I have, in each subsection of this webtext, advocated for a broader understanding of the kinds of digital or digitally-enhanced activism currently underway. By the time this publication is made available to readers, there will already be new ways for users to engage digitally. I have presented several opportunities for educators to incorporate these types of digital engagement activities into their own classes as part of digital and visual rhetoric lessons, so that our students can be effective consumers and producers of digital information. And I also have advocated for a curriculum of civic rhetoric, similar to the kind Jeffrey Grabill (2007) talked about in Writing Community Change: Designing Technologies for Citizen Action.

While it is useful to provide a framework for any genre of writing, writing for social change is much broader today than it ever has been before. I now put forth a call to action, inviting teachers of writing and rhetoric to begin teaching this lens, through which our students can see how information is being mediated to them. Remember that we don’t want to produce graduating classes of automatons that could rival citizens of a dystopian novel. We want to produce an educated, civically-conscious class of citizens who consistently challenge the status quo, who value civil liberties, and who rise up against infringements on such liberties. We want to provide them with the tools—both technological and communicative—to help make this possible in the 21st century and beyond. This means we have to expand our notions of civic engagement and public or community writing beyond simply teaching them to write the letter to the editor.

To Be Continued…

To Be Continued…As rhetoricians and compositionists, we are acutely aware of the power of words. Indeed, words are action. The Apology of Socrates is a fine example of the use of language to persuade, defend, rebel against a dominant position in society. Activist artists of the 70s, 80s, and 90s—such as Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro (“Womanhouse”), Yasumasa Morimura, and Felix Gonzalez-Torres, who used images to impact identity politics—are a reminder that discourse extends beyond words on a page. It is through digital technology that we are able to experience the full power and range of rhetoric, messaging that is linguistic, visual, sonic, and performative, often simultaneously.

The privileging of direct action over digital engagement has to end, particularly when we are working toward teaching civic engagement in our English composition classes. However, this is likely to continue to be an uphill battle. Just as there are many pedagogues resistant to including technology in the classroom, there are activists resistant to accepting a new form of political, social, and cultural engagement.

The reality is that this generation comes to us with a modified understanding of engagement. They conduct their lives armed with media, technology, and mobile devices in nearly all realms. Kids as young as five years old can take and text a picture to a friend on a mobile device. Eight-year-olds can create and edit a digital movie. Twelve-year-olds can build a website. If we don’t begin teaching young people how to harness these tools for academic and civic purposes immediately, we are failing to fulfill our commitment to prepare them for success in the world beyond the ivory tower, never mind hold their attention in class.

Though today, the most common digital campaigns are a hybrid form of activism; that is, they use digital media to supplement boots-on-the-ground (BoTG) efforts, or “offline mobilization,” the increasingly participatory nature of Web 2.0 and the coming Web 3.0 technology should hint at an upsurge of civic participation online. The founder of Clicktivist.org notes that digital activism isn’t a replacement for BoTG activism, but a digital alternative, highlighting the “use of digital media for facilitating social change and activism” (“What is Clicktivism?,” n.d.).

I suppose the answer to one of the first questions I posed in this article is found in this simple definition. Activism isn’t, nor should it be, judged by actual, tangible, quantifiable change. Sometimes efforts can be directly linked to accomplishment of goals; other times, the efforts simply contribute to general education or enlightenment, which might eventually lead to actual change. Changes that typically result from action, education, and awareness are the direct results of efforts that lead to changes in the hearts and minds of citizens (including politicians). This action can take place on a Montgomery bus, in an Atlanta diner, in a Facebook group, or in the media frenzy that surrounds the defacing of a governmental website.

It’s important that we reframe our narrow views of activism in this new, highly digital world. We didn’t depreciate the efforts of activists in the '80s who stood in a quad and distributed flyers about the AIDS epidemic or those of the '30s who simply gathered in the basement of City College of New York and “argue[d] constantly about how to solve the problems of the world” (“CCNY Rebels,” n.d.). Rather, we have studied these activities and might consider all of them valuable to some degree in the ongoing effort to understand and improve the world in which we live.

Engagement-oriented discussions about societal issues are relevant and are underway in multiple platforms today. In the 21st century, there can be no useful delineation of online and offline engagement practices. Rather than try to pit one against the other, it would be much more useful to activist scholarship and activism in general if instead we worked together to strengthen the skills—rhetorical, digital, organizational—of activists in order to make movements and campaigns more successful.

As activist scholars, we should continue to interrogate new forms of activism, to challenge the effectiveness of various mediums, because in the end, we want the work we do to matter. But we have to be very careful not to denigrate one another’s efforts or undermine the efforts of our students. We cannot breed activists: they are born through a careful combination of passion, education, and opportunity. As teachers, we can expose students to tools and information that will feed the education piece. We can provide students the opportunity to engage. We can, and should, assess the effectiveness of students' rhetoric, but ultimately, the degree of passion they have (or don’t) will determine the effectiveness of their work . . . and this is true whether they are taking action directly, in BoTG fashion, or digitally.

I look forward to the evolution of mindset in the vast ways we can apply 21st century literacies in our work developing student writers. There is a need for scholarship on the hybridization of civic and digital in the writing classroom, and hopefully many teachers will respond to the call to begin teaching digital engagement, advocacy, and yes, activism. We need to work together as scholars to ensure that these new, digital and digitally-enhanced forms of activism and civic/political engagement are productive and ethical. Without rigorous debate on the merits, pedagogical approaches, and effectiveness, we won’t be able to ascertain the true value of doing this kind of work in our classes.

Still, we should remember that any degree of engagement is better than no degree of engagement. While I work diligently to nurture more digital activism in my college classes, I acknowledge the many forms that engagement might take. Some of my students are simply comfortable joining a conversation online for the duration of our semester, while others take ownership of a cause or issue that is already near and dear to their hearts and run with it. If either path taken by a student leads to increased learning and experience, I can be proud of the job I’ve done. After all, I’ve helped play a part in their development as a citizen of this world, and I’ve shown them just how to harness a few tools and forums that are already part of their daily lives to influence change . . . to have their voices heard in a way that really matters.