Notes

- Barbara Warnick and David S. Heineman (2012) defined "cybercitizen" as one who “uses Internet technologies to participate in traditional civic activities (voting, engaging in public debate, protesting, paying taxes, etc.)” (p. 138).

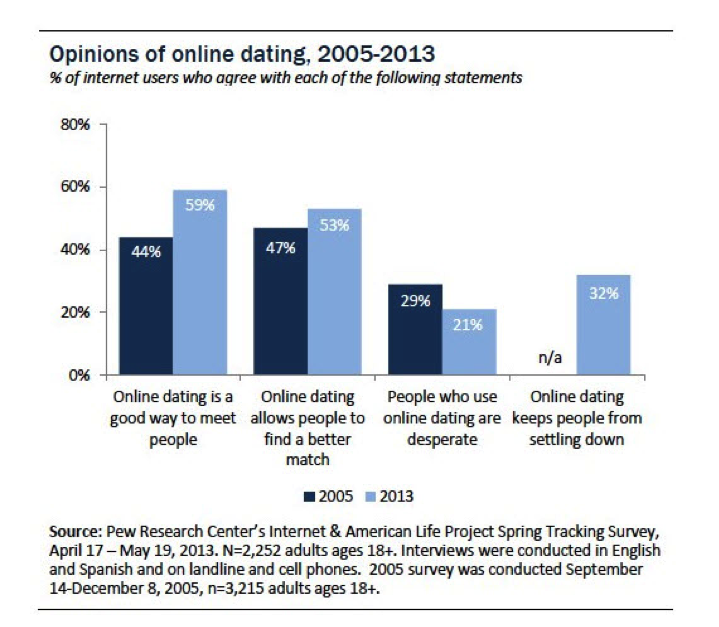

Return to text. - The number of users likely to go out on a date with someone they met online was up 23% between 2005 (43%) and 2013 (66%). The number of married couples who say they met online has doubled in the past eight years, and there is a clear difference between older individuals and younger individuals in their propensity to date people they’ve met online. The acceptance is generational. Perhaps the most interesting finding in this study is that 59% of Internet users believe that online dating is a good way to meet people, and this is a fifteen-point increase from 2005. If acceptance of this online activity that is typically considered a personal and private activity (one that should happen organically, in a face-to-face setting) has evolved so significantly in less than a decade, one can only imagine that the acceptance of the online variation of other similarly traditional in-person activities (activism, for example) has evolved likewise. Also interesting is that “5% of Americans who are currently married or in a long-term partnership met their partner somewhere online. Among those who have been together for ten years or less, 11% met online” (Smith & Duggan, 2013).

Return to text.

Return to text. - Dadaism (WWI) and Situationism (Situation International France in 50s and 60s) were early movements started in response to “consumer culture, military/colonial powers, and the disabling ideological ‘spectacle’ generated by global systems of mass communication” (Lievrouw, 2011, p. 29) . Both of these movements criticized dominant political and economic regimes, and both served to act against capitalism, militarism, colonialism (had a pro-Marxism bent). In an illustration of students longing for engaged and experiential learning and rebelling against the top-down method of learning, in 1966, student radicals at the Sorbonne joined the Situationist movement, decrying the university as but a “machine geared to produce spectators, rather than actors, in society” (Lievrouw, 2011, p. 40).

Return to text. - Categories of “Causes Advanced or Defended in Digital Action” (Joyce, Howard, & Rosas, 2013, p. 34-35)

RIGHTS and HUMAN WELFARE - Human rights

- Women’s rights

- Age-specific rights

- Contested citizenship rights

- Ethnic identity

- LGBT rights

- Freedom of information

- Workers’ rights

- Religious rights

- Anti-violence

- Intolerance

- Media bias

- Anti-corruption

- Against unlawful detention

GENERAL POLITICS - Government or regime change

- Democratic rights and freedoms

- National identity

- Cyberwar

- Crisis response

PUBLIC POLICY ISSUES - Technology

- Economics

- Health

- Legal

- Education

- Nature and environment

PRIVATE SECTOR - Anti-corporate, unethical business practices

Return to text. - According to the Global Digital Activism Data Set report (Joyce, Howard, & Rosas, 2013), there are several key purposes behind digital activist work. Here they are explained:

- Bypass, which includes efforts to bypass censorship and government surveillance online

- Synthesis, which is an aggregation or mash-up of digital content that serves to paint a more complete picture of a situation or event

- Resource Transfer, which includes raising funds/soliciting donations through digital means

- Co-Creation, which is collaborative work through digital channels to create manifestos or plan events

- Mobilization, which includes calls to action sent digitally or calls to act via digital channels (email, for example)

- Network-Building, which includes making connections in digital forums with others who have shared interest in the cause or issue or event

- Technical Violence, which is hacking for the purpose of disruption or destruction.

Return to text.

- Cyberterrorist, a term coined in the 80s to mean a combination of terrorism and cyberspace, has varying definitions. According to NATO, cyberterrorism is “a cyber attack using or exploiting computer or communication networks to cause sufficient destruction to generate fear or intimidate a society into an ideological goal” (as cited in InfoSec Institute, 2012). The Department for Homeland Security defines it in this way: “a criminal act perpetrated through computers resulting in violence, death and/or destruction, and creating terror for the purpose of coercing a government to change its policies” (as cited in InfoSec Institute, 2012). And in a governmental report to Congress, it is expanded in this way: “politically motivated use of computers as weapons or as targets, by sub-national groups or clandestine agents intent on violence, to influence an audience or cause a government to change its policies.” The justification for such expanded definition is that “DOD operations for information warfare also include[s] physical attacks on computer facilities and transmission lines” (Wilson, 2005, p. 4)

Ultimately, the idea of cyberterrorism could be viewed as an anti-concept, an exclusively political term crafted for the expedient demands of a post-cold war, post-9/11 America. There are no consistent definitions of it; it’s so broad as to encompass all of those (even reasonable Americans who want to challenge the United States government's over-reaching authority) detractors, and all existing definitions seem to be self-serving by the institutions or departments offering them up. Return to text.