Tattered, faded book cover with battered lower right corner. Text reads: The Dreamer’s Dictionary, by Lady Stearn Robinson & Tom Corbett. Image contains a purple moon, butterfly, hummingbird, and sleeping face.

For this project, I composed an original audio drama, “Night Visions: An Audio Drama,” performed by me and actor Paul Melendy. “Night Visions: An Audio Drama” is a mashup of several dramatic genres. The audio drama, now often delivered by podcast, is a later iteration of the radio play. However, radio plays are typically performed (and broadcasted) live with all of the performers present; this is perhaps less true of the modern, digital audio drama. Additionally, audio dramas are often shorter than full-length staged plays, but mine is shorter still, with just two compact scenes, in order to meet the requirements of the course rubric; it likely has more in common structurally with a 10-minute play.

It might also be classed as a dream play in that the protagonist, Man’s, dreams constitute an important part of the action of the play. I certainly was hearkening back to earlier dramatic works that feature dreams in various ways, most especially Agnes de Mille’s (1943) well-known dream ballet from Oklahoma!. However, the affordances of the audio mode allowed me to uniquely experiment in this well-established stage genre that is more commonly evoked through visuals such as choreography, lighting, or set pieces by considering how it could be effectively represented exclusively through sound. Moreover, I believe that composing sonically is what endowed me with such freedom to experiment with genre; the conventions of the audio drama are much more nebulous and encompassing than those of stage dramas, perhaps because it has a shorter history and is therefore less overwrought with generic expectations.

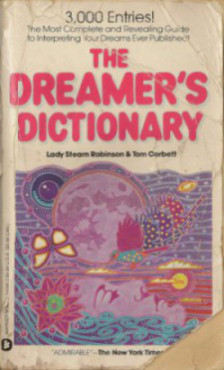

"Night Visions: An Audio Drama" was inspired by the cover of Lady Stearn Robinson and Tom Corbett’s (1986) The Dreamer’s Dictionary. The book is precisely what it sounds like: a dream dictionary with thousands of alphabetical listings that one can reference to interpret their dreams. I’ve had it since I was a teenager; it has been my almost constant companion throughout my life and now occupies a permanent place on my bedside table, right on top of my dream journal. Going into this project, I knew I wanted to write an audio drama but I wasn’t sure of the subject matter. One morning I woke up after experiencing two particularly vivid dreams the night before. I pulled out my dream journal and The Dreamer’s Dictionary, and suddenly it struck me that that the subject of my drama could mirror my experience—dreaming, waking, referencing, and analyzing.

In fact, the visual that inspired this drama is threefold—my dream dictionary, my dream journal, and my dreams themselves. The Dreamer’s Dictionary (Robinson & Corbett, 1986) serves as the thematic inspiration for my drama and is also featured in it as Man’s own dream reference guide. Additionally, the actual content of my dreams infuse the piece; all the dreams that Woman reads from Man’s journal are excerpts from my own dream journal. So although I was unable to physically capture the visuals of those dreams in the same way as the book cover, I still wanted them to be aurally present in the play. Simultaneously, my intention was to construct the dream sequence in a way that conjures strong mental images in the audience, despite its delivery in the aural mode.

Using these images to inform my ideas, I crafted this audio drama in several steps, beginning with writing the script. When I started writing, I knew the play was about an artist who was obsessed with understanding his dreams. However, I wasn’t sure of the reason for his obsession. Halfway through writing it, I discovered his secret motivation, which is that heartbreakingly he has been diagnosed with macular degeneration, and eventually his dreams will be his only way of experiencing the visual world. The theme of blindness has appropriately had a long history in the genre of the audio drama, from Samuel Beckett’s (1956) All That Fall to, more recently, Erin Anderson’s (2014) experimental Our Time Is Up. I see Man’s story as adding to that particular genre tradition, although it is also somewhat based on the true experience of a family friend. Finally, I carefully curated the content of Man’s dreams from my dream journal, all of which were genuinely written in that confused, half-awake state that is otherwise hard to capture.

Once the script was written, I began the process of assembling the audio assets, starting with the dialogue. After consulting with my fellow performer Paul, we decided to record our lines separately in an effort to alleviate any pressure to achieve a “perfect” take. I then selected the best take for each line and spliced it all together, a phase in which I experienced significant technical difficulties while becoming familiar with Audacity. Finally, I collected the remaining assets, including sound effects and music, all of which were located online. With the exception of Edith Piaf’s (1956) “Non, je ne regrette rien,” all materials used are licensed under Creative Commons. Each of these sounds was layered on top of the existing foundation of the dialogue.

The two most significant rhetorical decisions I made in this piece were to make the setting sound as natural as possible, while also trying to depict the dreams in a haunting and evocative way. These goals may seem contradictory, yet I think they are indeed complementary. I deployed several strategies to achieve naturalism, regardless of the fact that the dialogue was recorded by the performers at different times. Many of the sound effects were used to create the impression that the audience is in the same room with Man and Woman. For instance, at the beginning of the second scene, just after the alarm clock goes off, I inserted a clip of a quilt rustling; this effect simulates the sound of the couple waking up and turning over in bed. During the editing stage, I chose to include the actors’ breathing, and I made other subtle choices like adjusting the volume of Woman’s footsteps depending upon whether she was approaching or moving farther away from Man, from whose auditory perspective the narrative is told.

Simultaneously, I needed to convey Man’s dreams in a distinctly non-naturalistic way; they had to sound different enough from the rest of the dialogue that the audience would be able to recognize them as something “other.” While I wanted the dreams to sound suggestive and separate, I was wary of them coming across as facile, a simplistic audio rendering of the dreams. In point of fact, my purpose was to position the dreams as what Theo van Leeuwen (1999) called “sound acts” (p. 97). The dreams are not simply representations or expressions of a dream; they act in the play. The dreams-as-action build throughout the drama, culminating when Woman reads the pregnancy dream aloud. As she reads, her voice fades into the background, becoming a subordinated auditory “texture,” while the dream sounds increase in volume to demand that the audience hear them as the dominant sound “gesture” (p. 112).

I also thoughtfully considered the role of silence in my audio drama. As Heidi McKee (2006) has said, citing the work of François Jost, silence is not simply an absence of sound, but rather an “absent presence” that “traces noise” (p. 351). The silences not only enhance the naturalism of the play, such as the natural breaks in the flow of the couple’s conversation, but also emphasize moments when language fails, such as when Woman discovers why Man feels disconnected from his art and is preoccupied with his dreams. Silence is very much a presence in that moment, tracing the things that cannot be said.

Moreover, “Night Visions: An Audio Drama”‘s deployment of voice and vocality is very much aligned with the paradoxes described by Erin Anderson (2014). That is, voice is often used in the service of spoken language in this drama, as it is with almost any audio drama. The characters’ voices are the audience’s primary way of experiencing them as individuals whose bodies are invoked by their speech, yet still deferred (in much the same way that McKee (2006) thinks about silence). However, I deliberately allowed for non-linguistic vocality, particularly in Woman’s crying at the end of the first scene, which works to further the realism of the characters’ emotional responses.

I made many other rhetorical choices when composing “Night Visions: An Audio Drama,” yet I hope the most poignant is the use of tension in what appears to be opposites, both thematically and aurally: knowing and not knowing, vision and blindness, despair and hope, voice-as-speech and voice-as-sound, sound and silence, real life and dream life. Ultimately these binaries are not necessarily reconciled, but remain present in the drama as a both-and, giving “Night Visions: An Audio Drama” its complex, bittersweet, tone.

References

Beckett, Samuel. (1957). All that fall. London: Faber and Faber.

de Mille, Agnes (Choreographer). (1943). Oklahoma!. New York, NY: Broadway.

Audio Assets

Adam_N. (2012, September 30). Kiss 12 [Audio file]. FreeSound. Retrieved from http://www.freesound.org/people/Adam_N/sounds/166153/

Alexftw123. (2012, April 25). Car acceleration inside car [Audio file]. FreeSound. Retrieved from http://www.freesound.org/people/alexftw123/sounds/152661/

Bat-Shimon, Y. (2008, May 26). Invocation [Sound file]. On Yael-Bat Shimon Improvisations 05.04.08 [Album]. Somerville, MA: ARTSomerville. (Recorded on May 4, 2008). Retrieved from https://www.jamendo.com/en/track/173642/invocation

Cmorris035. (2013, November 16). Thick bed cover sheet blanket ruffle (16-44.1) [Audio file]. FreeSound. Retrieved from http://www.freesound.org/people/cmorris035/sounds/207274/

erinand. (2014). Our time is up [Audio file]. SoundCloud. Retrieved https://soundcloud.com/erinand/our-time-is-up-excerpt

Hutsvoid. (2013, August 12). 4 days newborn crying [Audio file]. FreeSound. Retrieved from http://www.freesound.org/people/hutsvoid/sounds/196746/

Kwahmah_02. (2014, October 5). Alarm1 [Audio file]. FreeSound. Retrieved from http://www.freesound.org/people/kwahmah_02/sounds/250629/

Motion_S. (2014, February 10). Calm waves crashing against a beach [Audio file]. FreeSound. Retrieved from http://www.freesound.org/people/Motion_S/sounds/218387/

Omar Alvarado. (2013, September 13). R05_0646 [Audio file]. FreeSound. Retrieved from http://www.freesound.org/people/Omar%20Alvarado/sounds/199656/

Ondrejtis. (2007, October 6). Edith Piaf – Non, je ne regrette rien [Video file]. YouTube. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q3Kvu6Kgp88

Pogotron. (2008, September 29). Turning pages [Audio file]. FreeSound. Retrieved from http://www.freesound.org/people/Pogotron/sounds/60836/

Qubodup. (2013, April 14). Whining dog [Audio file]. FreeSound. Retrieved from http://www.freesound.org/people/qubodup/sounds/184808/

SamKolber. (2013, December 9). Heartbeat [Audio file]. FreeSound. Retrieved from http://www.freesound.org/people/SamKolber/sounds/210027/

Soundmary. (2011, April 2). Door close [Audio file]. FreeSound. Retrieved from http://www.freesound.org/people/soundmary/sounds/117614/

Squareal. (2014, May 11). Car crash [Audio file]. FreeSound. Retrieved from http://www.freesound.org/people/squareal/sounds/237375/

Yuval. (2013, November 6). Footsteps rug [Audio file]. FreeSound. Retrieved from http://www.freesound.org/people/Yuval/sounds/205731/

Image Asset

Robinson, Stearn & Corbett, Tom. (1986). The dreamer’s dictionary. New York, NY: Grand Central Publishing.