Cavar and I decided last week that we'd both add to this doc by today, one week later, and our two approaches to this deadline make for an amusing mirror, or I'm feeling that way, anyway, as I write this. Cavar started writing immediately post-call, and I'm here now because I said I'd do this by today, although I could probably fudge the deadline if I needed to. The plugged-up drain Cavar mentions above feels like an apt description for a writing process in which I procrastinate until guilt keeps me from doing anything that isn't This. Now that I've started this paragraph, I feel better about it all; I'll probably just sit here for an hour or two in my kitchen. It'd be harder, maybe, at this point, to leave this doc. If a Google Doc were a room, a mansion, what would it look like if it were a memory palace?? All whiteboard walls? (If you had enough paint, could you make an entirely empty house look rich?) (Is that what fiction writers do? Can I do that, too? Here?)

I'm still working towards a confidence in writing that allows me to easily sit down and do work like this. The writing isn't as intimidating, I think, as the sitting down. It feels both funny and dismaying, how the idea of "composing one's self" is so unlike ADHD (or my experiences with it, anyway). I need to compose myself before I can compose anything else, and that first step is the hardest part. Robert McRuer[15] (2004) is just one scholar who's thought about this double meaning of "composed" when it comes to composition studies: He began an essay with one of the word's dictionary definitions, for instance, highlighting that "Webster's Dictionary authoritatively defines 'composition' as a process that reduces difference, forms many ingredients into one substance, or even calms, settles, or frees from agitation" (p. 48). This composition, the kind that comes before my writing ever begins, is a matter of endless planning. Ruminating? Definitely counts as writing.[16] My moods and motivations swing throughout the day, I feel fatigued no matter how much I've been sleeping, and side obsessions side-eye me like sirens during the hours I do feel energized enough to write. (My sirens are immensely asexy: 1000-piece puzzles, Dungeons & Dragons spells with all their varying statistics and components, new black ink that I haven't done nearly enough drawings with as of yet.) I'd love to finally find my ideal work schedule and designate as much time for play and rest as I specifically need to feel healthy and find work doable, to have repeatable methods of doing work, to have habits. Streamlined is a tempting aesthetic. Instead, I feel like I'm rethinking and relearning how to write every time I try to do it. Maybe it's good fodder for thought, but it's anxiety-inducing, never being sure if I'll accomplish what I set out to do on a given day. (And then again, I do love the endless effort of trying to overcome that anxiety: It's a delicious puzzle to try to solve.)

Between my initially writing that last paragraph and the current moment, I was diagnosed as autistic. (I attract terms that begin with A, apparently.) It's another angle with which to auto-annotate my anarchy. In an article on autistic disruptions and trans temporalities, Jake Pyne (2021) wrote, for instance, "Neurotypical time is assumed to be not only natural but also productive. ... In contrast to the developmental focus on efficient forward movement, the writing of autistic people themselves is often haunted by a longing for an alternate past in which one could have been acquainted with one's autism decades before" (p. 349). (Add to that my maybe-it's-ADHD habit of getting caught up in my own head, too.) If I have a (neuro)queer relationship with time, it's not a productive one in the sense of capitalism and neurotypicality. If many time travelers do their work in an effort at productivity, at improving things for someone or another, I trip (stagger) through time backwards and forwards, usually trying to take things slower, to focus more, to nap less. In those senses, academia is awful for me—I never do things on time. (And then again, I'm not yet sure where else to go.)

Scholars of queer composition in particular have advocated for a composition that's less composed (productive, neurotypical). Jacqueline Rhodes and Jonathan Alexander (2015) wrote, for instance, "We understand queer composing as a queer rhetorical practice aimed at disrupting how we understand ourselves to ourselves. As such, it is a composing that is not a composing, a call in many ways to acts of de- and un- and re-composition" (Introduction). In "How (and Why) to Write Queer: A Failing, Impossible, Contradictory Instruction Manual for Scholars of Writing Studies," Stacey Waite (2019) encouraged readers to not stay "on topic," suggesting they/we "drift gleefully off. Get lost" (p. 44). Other bits of advice in that chapter include "Don't become an authority on your subject" (p. 46) and "Don't summarize your argument at the end so we know where we've been and what you've done and accomplished. What you've written should not always be articulable in the tidiness of review. It should be an epic failure of a thing" (p. 48). I love and hate all of these suggestions: It must be so much easier to say these things as a tenured scholar or a teacher with a decade of experience than as a 25-year-old graduate student, though that's hardly a sensible critique.[17] The idea that we need to learn rules before we can break them is tiring, if it's true, but I can't subsist solely on queer composition studies; I'm still trying to figure out how to do the things I'm supposed to subvert and queer later on. (After teaching introductory college writing courses for five semesters now, I still wonder: What am I even meant to be teaching in the first place? It's not pondering so much as panicking.) The way much of scholarship in queer comp reads, the path to queer enlightenment feels almost linear: After first learning all the wrong things, the queer composer begins to try rejecting and subverting those things. As someone coming of age into this field, I feel like I'm traveling both these paths at once rather than one at a time, trying to learn how to compose myself even while I de-/un-/re-compose myself. The latter's always come more easily to me, but I wonder if I need to be doing both.

If there was anyone to try this with, Cavar is kind of (quasi-) perfect. They encourage my uncomposed, queer writing even as they do the very opposite, urging me to complete tasks on time rather than procrastinating or abandoning them. This webtext would never have been submitted anywhere, revised, or even finished, probably, if I were writing it alone. I don't think I would have ever begun it. It's their encouragement in tandem with Kairos's revision notes that have me sitting at my desk right now—my own self-control doesn't hold that kind of power over me.

Of course, who's to say that this push towards composition isn't queer? It feels less authoritative than kinky (when Cavar and Kairos do it, anyway). I don't have to do this. Constraints aren't necessarily limiting. Or, if they limit my movement, they only do so to aid me in the sitting down and composing myself that I find so difficult. They do it with my consent. More than that, they do it with my encouragement. I do love them for it.

I'm thinking about how we talk about each other in general, in this doc, Cavar and I: I don't know if anyone else has ever used both my pronouns in the same sitting or setting, actually, and it was nice that they did so above. "Nice" implies politeness[18] on their part, but when I think of that word here, I'm thinking on the nice feeling in my stomach or my chest that came when I read what they wrote just now (or what I read just now, which they wrote a week ago). I'm thinking about the discomfort that some of their words bring me, how I'm not sure I could ever separate the nice ones from the rest. A quick rule for choosing words? I have a friend who, unintentionally, uses any pronouns but ones with the letter "h" in them—"she," "he," "they," "hir." I could do some research here, maybe map out what works and doesn't on a table, look for patterns. With my first (romantic/sexual)(?) partner, or the first one with whom I had sex and attempted to navigate someone else's romantic attraction towards me, I made a Google Doc of columns: "yes," "no," "maybe sometime," or something like that; the rows were items like "holding hands," "giving flowers," "receiving flowers," "kissing," probably sex. If I made something like that here, what would I discover? Do I want to know?

I'll spend a moment or two, maybe, trying, then see how it goes—

A tangent, but maybe not. (A tributary?) I know ace people who feel uncomfortable talking about sex at all; I joke about it frequently, even try to tamp that humor down when talking to most people, but maybe I meet my limit when it comes to sex discussed more seriously, in reference to my own body/mind, even metaphorically. Is that important? Something to overcome?[19] For Cavar to attempt to traverse? I don't want to ask them to, I suppose because I still want some form of coupledom with them, an intimacy I fear would waver if I brought into the room a list of things I didn't like, or wasn't sure if I liked or not. Can I censor their use of "balls," and do I want to, even? I love scholarship that pushes at the limits of its genre in that way, stuff with curse words and first-person narratives. I fear that fearing the sound and feel of my memories of others' genitalia is—IDK, bad? Offensive? I've read scholarship that praises all manners of bodies, calls them beautiful, re/affirms their wonder, their lack of a need to be beautiful in the first place. Does my discomfort run against that grain?

(If anything, my bringing it up follows some of Waite's (2019) rules for writing queer, if following rules is queer at all, or the intention of Waite's rules in the first place: "Write queer because your writing and your self are not distinguishable" (p. 44), and "Be irrational, hysterical even" (p. 44). Not to mention: "Don't come to conclusions. Come to other things: inquiry, questions, failures, side roads, off-road" (p. 48), and "Don't take the road" (p. 48). Maybe, if I'm uncertain as to whether to instigate this discussion over the terms we use here, unsure if it "fits" or not even as I revise this webtext, that's okay. Alexander and Rhodes (2014) wrote, "Ultimately, we want to move beyond, perhaps even leave behind, the multicultural imperative to 'include' queerness as another 'difference' ... and explore instead how queerness in its excessive modes ... poses a unique and significant challenge to literacy. It is precisely in queerness's impossibility to be composed, in its excess, that its most important contribution to literacy, critical engagement, and writing" (p. 432). Maybe journal articles, or this webtext in particular, could stand to get a bit more poetic—not poetic as in pretty, but poetic as in vague, confusing, multiplicitous in potential meanings. There's possibility for varying interpretations of as well as responses to a text that isn't as cleanly cut as so many are.)

I guess what I'm bringing to this document thus far is a bit of a pushing back, which I hadn't planned on doing. Musings on boundaries, negotiation, or asking for such things in the first place? I like the idea of a document that re/negotiates its own boundaries, authors who re/define their relationship as they work, but at what point does my desire for space become a fear of commitment, of sex, of touch, of friendship, even? How can I articulate that desire when I want, at the same time, to talk to Cavar more, to keep writing with them? I'm not sure I have any idea how attraction works, platonic or romantic or familial or sexual. Do I love anyone at all? I'm not sure. I very much enjoy D&D, talking with Cavar, messaging a few other people. Being alone, listening to audiobooks, autumn. The word "love" makes me nervous—it holds so much expectation.

What is this text in the first place? In form, it most reminds me of some of the young adult novels I read as a teenager, the ones where a different author would write each side of a developing relationship: David Levithan and Rachel Cohn's Nick and Norah's Infinite Playlist, David Levithan and John Green's Will Grayson, Will Grayson. Its inspiration in letter-writing makes me think of epistolary novels: Evelina, The Color Purple, Dracula, The Perks of Being a Wallflower. These genres are ostensibly or initially concerned with two people—a writer, a receiver, the romance between them—but, in being published as novels, bring a new audience to those private correspondences. Or, rather, they were never really private in the first place: They were written with the intention of publication, directed at both the fictional addressee of each letter and at the audience witnessing the former's privacy. This text, too, was written with such intentions, though, in writing it, I've fallen into moments where I was writing much more to Cavar than to you (our own audience). In some parts of this text, "you" is you; in other parts, "you" is Cavar. That second-person fluidity comes in, I suppose, because we're not writing fiction: All of this is relevant to us, even is us, at times. Where is the balance between writing for each other and writing for you? How much do we explicate, and how much do we simply offer as primary source material that you might witness, drawing from it your own conclusions?

This has me thinking about epistolarity, particularly in novels, and all that's left on the cutting-room floor, all the obscured privacies that these characters might partake in. What would it mean to write the backchannels of character communication? What might it mean to expose the architecture of this document, even moreso than we are already—the hundreds and perhaps thousands of messages we've exchanged across platforms that will never make it here? At what point does transparency—hyper-intimacy—become intrusion? The more I talk to myself (and to you, and to you, the reader), the more it seems an ace framework is useful in understanding intimacy's limits. What makes an effective epistolary document, and what ought to stay, if you will, in the closet?

Cameron Awkward-Rich (2022) addressed this issue—this need for recognition yet anxiety around/refusal to partake in hegemonic narratives of trans [and queer, ace, disabled, Mad, neurodivergent, etc.] life—with the project of lyric. Lyric dissociates from the "I," is plural at its core, creates an atemporal (queercripped!) space where time stops and cedes to a "continuous present" (p. 136). As I write this, we are writing together. We are writing together since 2021. We always have been writing together right now. Right now is whenever we write right together.

Tony E. Adams and Stacy Holman Jones's (2011) "Telling Stories: Reflexivity, Queer Theory, and Autoethnography" takes on a similar form to that of this text, much of it written in the second person. Their use of the tense, however, isn't that of one author speaking to the other (or to readers) but, instead, one that groups Adams and Holman Jones together in that pretty, evocative way that only good second-person writing can. They begin, for instance:

May 2007: You have the whole day to work, to write together. You are working on a handbook chapter that traces the connections and possibilities of writing autoethnography and queer theory together (Adams & Holman Jones, 2008). Until today you have been writing alone, sending drafts to each other through email, each inbox arrival a gift. You are worried that getting together will spoil the momentum and excitement of your exchange. Thankfully and perhaps inevitably, you are wrong. The day flies, as do your ideas, your fingers floating on the keys. You finish the essay and send it off, feeling grateful for your collaboration and your work. A few months later, you are invited to share your essay at a conference and to recast it for a second and then a third edited collection (Holman Jones & Adams, 2010a, 2010b). Each time you return to this work, you reconsider, revise, restructure, and write something new. Circling back, it is difficult to know where to start. (p. 108)

(I want to keep quoting them; I love these lines.) Adams and Holman Jones (2011) noted in their essay that its focuses of "autoethnography, queer theory, and reflexivity share commitments that are personal and political, tense and complicated, disruptive and open-to-revision, humane and ethical. By interrogating the method, paradigm, and practice, we discern and document the ways selves enact—live—cultures as well as how cultures live in and through selves ... . We also work to find ways selves can be used physically and discursively to disrupt insidious cultural practices and norms" (p. 111). Adams and Holman Jones's text is itself ethnographic, working as an example of the kind of queer, autoethnographic, reflexive work it discusses in the third person. The second-person address isn't necessary to do this, though. I'd expect most autoethnographic texts, on the contrary, to be written in the first person, with "I"s and "we"s and "us"s (or "Us"s, as Cavar calls them). Adams and Holman Jones's "you" invites readers to pretend for an hour that readers are Adams and Holman Jones rather than drawing a line between themselves as authors and their readers, between "us" and "you."

Cavar and I don't make that specific move with this text, but we're propositioning you, nonetheless, to join us. We won't offer a definitive list of takeaways for this text, as we'd like to think that there are more possible interpretations of this text's point than we could imagine and articulate. We offer here, however, a start to that list, a few thoughts and questions you might find or seek out as you read, listen to, or otherwise take in our work:

♥ How can we reimagine the work of composition and collaboration to include, embrace, and aid queer, neurodivergent, and/or disabled writers (and their queernesses, tics, constraints, and capabilities)?

♥ What specific practices or mindsets could sprout from such reimaginings? How could these be drawn on or taught in the composition classroom?

♥ Maybe this text is an example of negotiation within a relationship between several people, something not dissimilar in form from breaking up via text message. Instead of seeking low-effort and fast separation with our messages, though, we text rather than speak aloud because we find ourselves more capable of (or maybe just more interested in) writing our feelings for each other than communicating them in person.

♥ Maybe this text is an example of collaboration between scholars, between grad students, or over distance, something that readers might use as a guide or reference for their own collaborative efforts.

♥ There isn't enough representation of asexual/aromantic/queerplatonic/neurodivergent/ADHD/autistic/disabled people or relationships in either popular media or scholarship, so this text seeks to fill a small space in those gaps, to offer new perspectives for readers who don't identify with those terms and ideas/hope/solidarity to those who do. What can asexual/aromantic/queerplatonic relationships/collaborations look like?

♥ How does our relationship/collaboration work with the help of digital tools? (Would it look different if we lived in the same apartment rather than the same Google Docs?)

Ulysses, love and light, but if I lived in the same apartment with you, I think I'd go even crazier than I already am. I think you'd feel the same about living with me!

If you're into it (halfway through this text as you already likely are), we invite you to join our threesome (officially or unofficially) and to consider what that joining could mean or do. Bring a friend, if you'd like. (More than one, of course, is also acceptable, though you don't need us to tell you that.) This is a text for single people or life partners, scholarly or otherwise. With it, you might compose essays, novels, partnerships, sex. (In my personal opinion, you should use it to think about planning a Dungeons & Dragons campaign.) (This is, of course, Ulysses writing.)

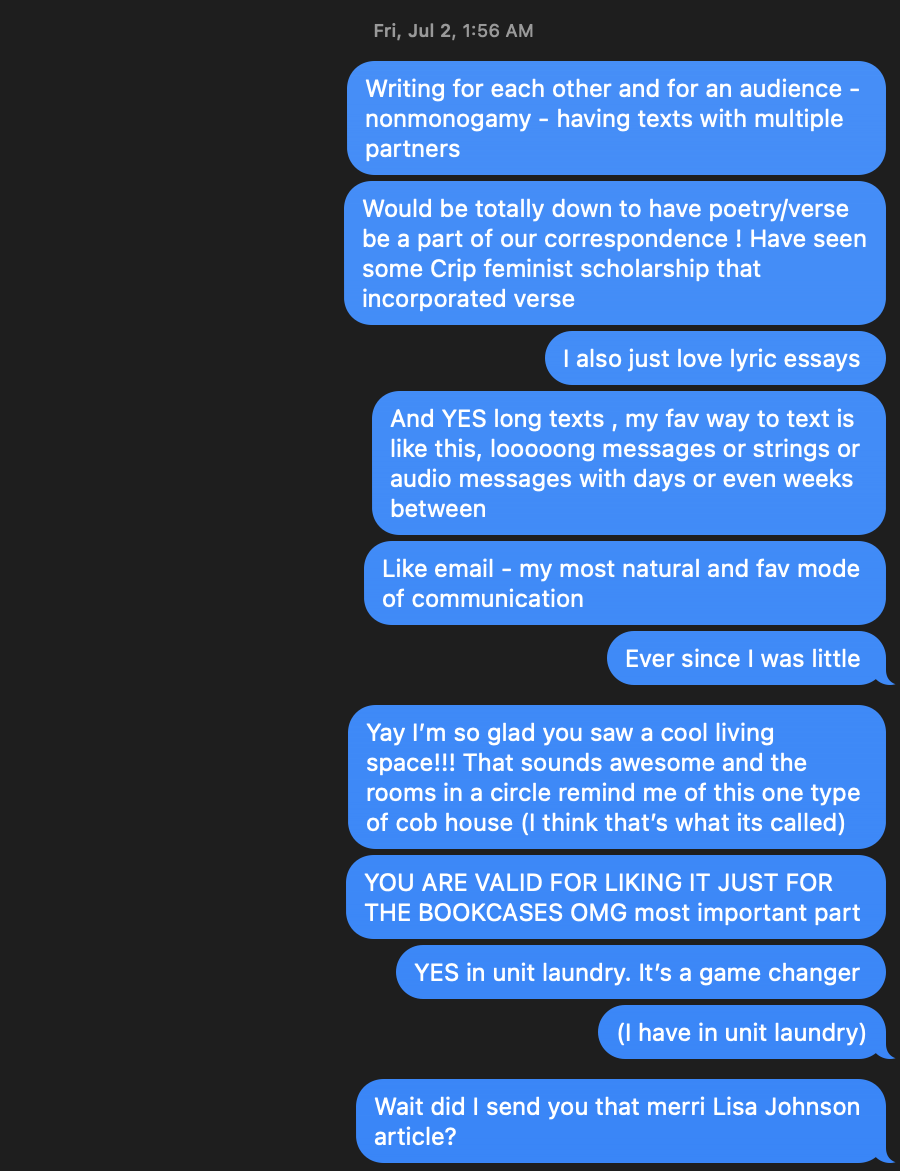

Cavar: Writing for each other and for an audience—nonmonogamy—having texts with multiple partners

Cavar: Would be totally down to have poetry/verse be a part of our correspondence !

The long texts line and this screenshot being a long text <3 <3 <3 ... jckdkjsdcjkn at this mix of daily life and apartment talk and theory yesss

WE LIVE OUR THEORY!!!

Have seen some Crip feminist scholarship that incorporated verse

Cavar: I also just love lyric essays

Cavar: And YES long texts, my fav way to text is like this, looooong messages or strings or audio messages with days or even weeks between

Cavar: Like email—my most natural and fav mode of communication

Cavar: Ever since I was little

Cavar: Yay I'm so glad you saw a cool living space!!! That sounds awesome and the rooms in a circle remind me of this one type of cob house (I think that's what its called)

Cavar: YOU ARE VALID FOR LIKING IT JUST FOR THE BOOKCASES OMG most important part

Cavar: YES in unit laundry. It's a game changer

Cavar: (I have in unit laundry)

Cavar: Wait did I send you that merri Lisa Johnson article?[20]

[15] We're as sick of the McRuer references as you are. We reference him as an originator of "composed" as we use it. Yet his name also composes, in Webster's sense, in that it "settles" the matter of credit in scholarly discourse, providing the reader a familiar name, a predictable citation, a closure of thought rather than an opening.

[16] The Twitter account @CountsAsWriting is a tongue-in-cheek archive of nominally uncomposed activities that, the account asserts, count as writing. It both creates original tweets and retweets others' submissions, creating a literary ecosystem friendly to the uncomposed writer—the writer who eats, sleeps, stresses, tweets, and ruminates themself into an anxious corner from which they struggle to emerge.

[17] Waite (2019) does acknowledge this, writing, for instance, "Once a journal told me to 'take all the narrative out' of an essay, and I did. Once I didn't. Once I told one editor to fuck off, but only after my book manuscript was accepted for publication" (p. 50).

[18] Niceties are overrated. These normative—white, abled, sane, middle class—"discursive expectations ... [work to] [habituate] hierarchical social dynamics" (Cedillo, 2018) that prioritize civility and distance over emotional density. Niceties can also function as euphemisms for oppressive practices; disabled poet, scholar, and activist Mel Baggs (2018) referred to these as "Snake Words." Snake Words, which, as I (Cavar) note elsewhere, "conceal and consolidate structural ableism" (Cavar, forthcoming), emblematize the violence embedded in white, middle-class, abled/sane notions of niceness, both in protecting the powerful and in subjugating the Other(ed) (refer to Stitch, 2020).

[19] Eli Clare (2009) likened the ableist impulse to "overcome" one's limitations to a hostile mountain that draws crips in but refuses them (us) safe passage (pp. 1–13).

[20] The article I am referring to is Johnson (2021).