Summoning Duende: Afro-diasporic Religious Listening Practices in Funkadelic and Childish Gambino's Music

Vanessa J. Aguilar

Introduction

Spanish poet Federico García Lorca (1931) released Poema del Canto Jondo (Deep Song Poem), a collection of poems that highlights the symbolic significance of a spiritual force called duende. Duende is a supernatural force that becomes embodied in a flamenco singer or performer. García Lorca defined duende as "a mysterious power which everyone senses, and no philosopher can explain" (Nava, 2017, p. 153). The origin of duende "derives from the phrase duen de casa or dueño de la casa, 'master of the house,' and refers to a folkloric trickster figure similar to a goblin or poltergeist" (Wilson, 2008, p. 75). According to Maria Christina Assumma (2005), "‘duende' [is] literally a spirit, ... a profane trance, a manifestation of musical emotion which goes beyond a religious context" due to its ability to captivate and move an audience (Assumma, 2005). In Juego y Teoría del Duende (1993), García Lorca addressed the idea that duende's power cannot be explained but alluded to spiritual possessive forces, emotions, and (un)consciousness of duende's manifestation. While analyzing the embodiment of duende, García Lorca encouraged his readers to see that music and performance are an embodiment of this supernatural force with possessive abilities.

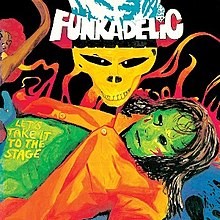

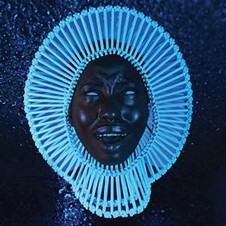

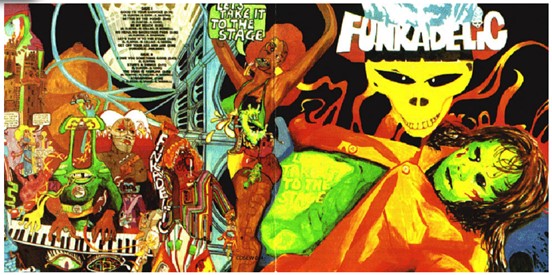

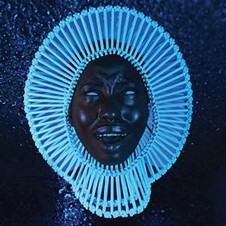

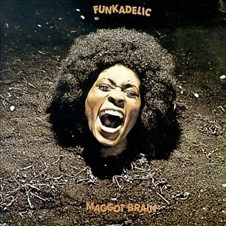

I situate the duende away from García Lorca's association to Spanish-European music such as flamenco and reposition the duende as a spirit rooted in Afro-diasporic religion, rituals, and music, serving as a spiritual guide. I consider duende as a foundational concept in the musical genre of funk. The conjuring of duende in funk music is found in active listening practices that focus on the musical elements such as the drumming breaks and vocal utterances. I argue that duende originated in Afro-religious practices of spiritual ecstasy and is reduced as the "sounding Other" by mainstream audiences unable to hear the duende. Then, I examine how duende is adopted in the genre of funk music provided with two funk song examples; Funkadelic's "Good to Your Earhole" (1975) and Childish Gambino's "Riot" (2016). Duende's discursive power exceeds the musical performances, the album covers of Funkadelic's Maggot Brain (1971), Let's Take it to the Stage! (1975), and Childish Gambino's Awaken My Love! (2016) are imbued with vestiges of duende.

Afro-diasporic Religions and Listening Practices

The incantation of duende aligns with the rituals of possession found in Santería, Candomblé, Lucumí, and other variations of Yoruba religious practices. Applying rituals of possession to music transforms the musical performers, and they become "cantador enduendados [meaning] (singers endowed with the duende)" (Assumma, 2005, p. 207). Afro-religious listening practices rooted in lamentation, worship, prayer, and spiritualism are methods to invite duende into the body. Similarly, practitioners of Santería and Lucumí believe that these spirits are allies and often spiritual guides. In the ritualistic sense, practitioners do not only listen to the rhythms but actively invite the spirits they invoke. On the other hand, listeners of secular music often fall into the trap of not actively listening to the spiritual driving force of the performer. Jennifer Stoever (2016) suggested in her book, The Sonic Color Line:

The sonic color line describes the process of racializing sound—how and why certain bodies are expected to produce, desire, and live amongst particular sounds—and its product, the hierarchical division sounded between "whiteness" and "blackness." The listening ear drives the sonic color line. (p. 7)

Practitioners and community members in Afro-diasporic religions have different listening practices and are often mistaken as the "sounding Other" (Stoever, 2016, p. 11). Stoever claimed, "White-constructed ideas about 'sounding Other'— [stereotypes] accents, dialects, 'slang,' and extraverbal utterances, as well as ambient sounds—have flattened the complex range of sounds actually produced by people of color, marking the sonic color line's main contour" (p. 11). Through generations of imposed "otherness," invocation of spirits have been related as irrational and demonic. Similarly, funk music performers, like James Brown and Funkadelic, use vocal utterances that may be mistaken for irrationality by white audiences, which becomes a form of othering. Tricia Rose's (1994) book Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America examines how cultural Afro-diasporic forms of practices, and traditions are inserted in "stylistic continuities in dance, vocal articulations, and instrumentations ... creating Afro-diasporic narratives that manage and stabilize these transitions" (p. 25). The duende has a home rooted in transitions and conjuring not only in religious rituals but across Afro-diasporic music and cultural practices. It is important to take into account that the influence of Afro-religious music is practiced all over the world; it is deeply embedded within various musical genres today, whether the listening ear or body senses it or not.

I use the concept of the sounding Other and the manifestation of duende as the conceptual framework of what's being transpired across "Good to Your Earhole" and "Riot." There is an opportunity to join in and become enduendados as we hear and understand how the supernatural force of duende is manifested sonically across the two funk songs in relation to Afro-religious rituals and practices. In order to do this, I invite active listening practices that call forth summoning duende in Funkadelic's song "Good to Your Earhole." Then, applying these same practices, I work to hear how duende possesses Childish Gambino in "Riot," to understand how it is transformed in a call-and-response ritual, and to interrogate how duende exists in the world today on record albums.

Funkadelic's "Good to Your Earhole" Conjuring Duende

The rise of funk music introduced a new style that was coined by James Brown and George Clinton and his group, the Parliaments. The two are pivotal figures that represent two different geographical spaces of the U.S; the north and the south. In 1964, the Parliaments began as a doo-wop group, which later lost three of its members to the military enlisting. The original name, the Parliaments, was tied to their former record label company, Revilot (now known as Atlantic), and the group was forced to rename. After the new recruitment of band members and relocation to Detroit, the group was transformed into Funkadelic under the Motown label (Wright, 2008, p. 43). As an attempt to reclaim the lost band name, Clinton and the members coined P-Funk, or Parliament-Funkadelic, as a musical aesthetic (Kajikawa, 2015, p. 84). The groups' music highlights a transcendent spirit rooted in Black science-fiction, myths, and Afrocentric spirituality.

As Funkadelic's popularity arose, the band's lyrics promoted Black-centered political, spiritual, and psychedelic emphasis on what scholar Amy Wright (2008) called "funk as a philosophy" (p. 33). Wright explained that funk as philosophy advocates for equality and freedom, but what Funkadelic isn't conscious of is that they are not entirely free; they are being held captive by duende (p. 33). In the process of developing their funk aesthetic, Clinton's Parliament-Funkadelic group founded its image upon psychedelic Afro-centric spirituality. Funkadelic created "a counter-hegemonic philosophy of funk that was a deliberate rejection of traditional Western world's predilection for formality, pretense, and self-repression" (p. 37). Funk was a progressive reaction and rejection of mainstream norms (p. 37). Funkadelic refused to sound like a stereotypical band. Funkadelic fused together various elements of blues, jazz, soul, and rock to create a new psychedelic sound that transported its audience spiritually to new heights by redefining archetypical African American musical aesthetics (p. 38). Using spirituality as a focal point in their aesthetic, the group produced songs such as "Free Ya Mind", "Cosmic", and "What is Soul?" that indoctrinated enlightenment.

In 1975, Funkadelic released its second album, Let's Take It to the Stage! According to Wright (2008), "Clinton had created a philosophy that promoted freedom through musical, physical, spiritual, sexual, and now intergalactic release, which appealed to a broad audience, but the music and philosophy remain rooted in African traditions and the working-class Black experience in the United States" (p. 44). Using mythical and spiritual elements from Afro-religious practices Funkadelic achieved their newfound style, a style that possessed abilities to conjure spiritual forces like duende. Funkadelic's featured song "Good to Your Earhole" from their album Let's Take it to the Stage! displays instances of Afro-religious spiritual and bodily possession by duende.

["Good to Your Earhole" Lyrics by Funkadelic]

I'm going to give you what you're here for

I've got the means to take you there

I'm not here to kill you softly

But I promise to be good to your earhole

Put your hands together, come on and stomp your feet

Put your hands together, come on and stomp your feet, Lord!

Put your hands together, come on and get in beat

There's a good time waiting for you, come on and let's get free

Mashing your brain like silly putty

Leaving you in a better frame of mind

Drowning out the voices that bug you

But I promise to be good to your earhole

(Funkadelic, 1975, track 1)

Funkadelic's "Good to Your Earhole" began with 4 bars of musical elements such as the guitar, hi-hat, and drumming. Once the four bars were over, two voices crept in, overlapping one another and promising to "give you what you are here for / I've got the means to take you there" (Funkadelic, 1975, track 1, lines 1-2). The reverberations of the voices bleed into each other. I consider it the battle between duende and the singer. The battle becomes elaborated in the mimicking of first and second vocals which sound like the subconsciousness of the first vocalist. The layering of the voices provides examples of movement, in this case transcendence. When the cantador enduendado enters into a trance, his voice is ruptured by the overpowering duende. This is where the spirit of duende is summoned and visits the artist in an intense trance-like state. Funkadelic's futuristic spaceship descent in the background of the music transports the performer and listener. Therefore, the trance is a vertigo effect, a sensation in the body that leaves one feeling unbalanced and disoriented, a production of heightened awareness. The trance offers an alteration of time, space, and bodymindspirit. Taking into consideration the possible use of hallucinogens, I acknowledge that the duende's supernatural force does not require a drug induced state as one might assume when the group shouts "mashing your brain like silly putty" (Funkadelic, 1975, track 1, line 8). Rather, the duende's power possesses the band members' mind demonstrating ecstatic behavior, becoming the ultimate form of spirit possession (Raboteau, 2004, p. 59). Afro-religious studies scholar, Albert J. Raboteau noted that:

Commonly, the rites of worship consist in drumming the rhythms of the gods, singing their songs, creating a setting that they will come down and "ride" their devotees in a state of possession. The possession takes on the personality of the god, dancing his steps, speaking his words, bearing his emblems, acting out his character in facial and bodily gestures. (p. 59)

Possession is nothing to fear in Afro-diasporic religions like Lucumí, Candomblé, and Santería; rather, it is considered one of the highest encounters with spirits and gods. El cantador enduendado: "is manifested in the emotional meaningfulness of the lyrics and in the intensity of the voice" (Assumma, 2005, p. 207). In "Good to Your Earhole," the duende's goal is to "[draw] out the voices that bug you" (Funkadelic, 1975, track 1, lines 9-10). Now what are these voices? Are they society's expectations? Or are they ancestors serving as guides? Then, the singer yelled out "Lord!" just as his voice breaks, not fully able to cry out for help (Funkadelic, 1975, track 1, line 12). The duende is now in control just as it promises the audience and performer that "I'm not here to kill you softly / but I promise to be good to your earhole" (Funkadelic, 1975, track 1, lines 15–19). The duende forcefully pushes the band members into a not-so-irrational trance-like state, because remember the listening ear can mistake the duende as a sounding Other.

Mounting Ceremony: Childish Gambino's "Riot"

The duende's sweet promise of being good to the earhole requires exchange for temporary bodily summoning. The summoning is heightened in the next song by Donald Glover, who is also known as Childish Gambino. Known for his 2018 song and music video "This is America," Donald Glover, whose musical stage name is Childish Gambino, addresses the political and racial turmoil of gun violence and police brutality toward Black lives. Understanding Childish Gambino's musical aesthetic and inspiration builds upon his ability to conjure the duende. In "This Is America", Childish Gambino refused to address his intention and understanding of the music video in order to allow the audience to develop their own opinion rather than providing meaning to the symbolism of the creative performance. Centering ambiguity at the forefront, Childish Gambino captured the attention of various audiences. Meanwhile, scholars like Kimberly Eison Simmons (2018) noted in "Race and Racialized Experiences in Childish Gambino's '"This is America'":

W.E.B. DuBois' idea of double consciousness is applicable here and captured in Gambino's dance performance and facial expressions. At different times, Gambino's face reflects a sense of joy, pain, anger, frustration, fear and bewilderment. He glides to the music, is in step with the beat, and at other times, he has a hobbled walk where he stumbles. On one hand, these facial expressions and movements represent double consciousness and duality of being black in America with the realities of racism (feeling conflicted, wearing a mask, navigating different terrains fraught with competing feelings and emotions). (p. 114)

As Simmons addressed double consciousness, the duende also works consciously and unconsciously regarding its audience. Though double consciousness offers new insights on the music video for "This is America," I redirect readers to understand the power of the duende as a spirit that is infused inside the performer's body. For example, duende possesses Childish Gambino's facial and bodily expressions as he contorts through an inner battle with the duende that he invoked. Here, the duende is more seen than heard. The same representation of enchantment by duende is found in Childish Gambino's lyrics and musical performance of "Riot." Childish Gambino looped the drumming break found in Funkadelic's song, "Good to Your Earhole," as a sample for his 2016 musical creation titled "Riot." The sampling houses the duende that Funkadelic conjured. Duende's ability to transpire and transcend allows Gambino to become the new cantador enduendado just as he too, battles the spirit that reaches the depths of his soul.

["Riot" Lyrics by Childish Gambino]

Uh, ahhh!

Ayy

I can feel it deep inside my body

I've been watching all this all night

I got to move it

This pressure brewing

This world don't feel alright

Everyone, everyone!

Get down, baby, get down, baby

Fly, fly, fly, high

Ohh, uh

Everyone, everyone!

Get down, baby, get down, baby

Fly, fly, fly, son, ahhh! Uh

(Childish Gambino, 2016, track 5)

In this example, the lyrics decline after the second half of the song begins. Gambino (2016) yelled, "Get down, baby / fly, fly, fly, high," lines which are repeated until the song ends (lines 20-21). Heightening this radical change in form, the duende requires a state of alteration of consciousness just like he did to Funkadelic (Assumma, 2005, p. 206). At this point, the duende has mounted Gambino, epitomizing the power it holds over the body and carrying it through the song. In religions like Lucumí, Elizabeth Perez (2016) explained in her book titled Religion in the Kitchen, "Possession mounts are perceived as both conveying power of their patron deities and enlarge their religious lineages carrying proteges throughout their religious lives" (p. 115). If we consider the duende as a spirit with powers to mount, then duende has the ability to shapeshift and possess performers, similar to a deity. The performer's trance-like state challenges the listening ear and comes forth out of Childish Gambino's summoning, to either protect or serve as a spiritual guide in his riot. In my interpretation, the duende in Childish Gambino's song serves to seek justice in a world of systemic violence; meanwhile the duende seeks to provide as his spiritual guide.

In Childish Gambino's trance-like state, the possession targets the alteration of lyrical component and formulation of sentences decline as Gambino vocally expresses emotion. The emotions overcome his capacity to produce words while he is forced to repeat what he has already said. Both songs contain little lyrical substance while at the same time the duende's spiritual possession is the focal point in "Good to Your Earhole" and "Riot." Returning to the sounding other, we should not confuse or devalue what is transpiring in these songs. Often, religious rituals and exaltations produce what the West considers "speaking in tongues." "Speaking in tongues" is a phenomenon that is believed to be a divine language, but outsiders lack the comprehension of the meaning behind the words produced by the speaker. Rather than focusing on his vocal utterance as shrieks and yells, we should envision what is happening to Gambino's body as he sang "getting down baby, ... fly high," resembling a contortion and transcendence of bodily and spiritual possession. Though it is clear what words Childish Gambino uses, the content may be lost in translation to an audience who has not invoked the duende and considers these gestures as the "sounding Other."

Call-and-Response

The manifestation of duende is found in the climax of the cantador enduendado's performance which requires a call-and-response. Call-and-response is practiced within Afro-religions across the diaspora. Call-and-response is a way to engage the community, while also strengthening its ties with participants. In addition, the call-and-response provides a dialogue between the producers of music and its audience. Tricia Rose (2016) suggested it is the "dialogue between sampled sounds and words" (p. 39). For instance, in funk music, James Brown's songs often mandated for his listeners to move their bodies and often "clap [their] hands and stomp [their] feet" like in the song "Give It Up or Turnit A Loose" (Brown, 1986). In recent songs like "Riot," Gambino yearned for "everyone [to] get down baby [and] fly, high" (Childish Gambino, 2016, track 5, lines 7-9). Once the cantador enduendado seeks the audience's participation the cantador enduendado wants the rest of the listeners to join in the ritual. Duende's persuasiveness is the ultimate form of enchantment. It is so powerful that it makes its listeners unconsciously respond. In Funkadelic's work, the singer shouts "put your hands together, come on and stop your feet…/[then] Put your hands together, come on and get in beat" (Funkadelic, 1957, track 1, lines 4 and 6). Often, live performances achieve this call-and-response participation. In other cases, like a recorded song, listeners chant along in private and public spaces, such as night clubs and even when singing along in the car. Therefore, once the spirit is transported into the audience's bodies, they too begin an unconscious battle similarly to the cantador enduendado.

Remnants of Duende

The aftermath of the bodily possession is found on tangible material items promoted by Funkadelic and Childish Gambino's album covers. The presence of duende's spirit is not only heard sonically but is represented visually and can be mistaken as a visual and sounding Other. I interpret these album covers as representations of Afro-religious depictions of mounting the head or also known as crowning ceremony. Let's take for example Funkadelic's album cover Let's Take It to the Stage! illustrated by Pedro Bell (1975) (image below).

The album cover creates a stylistic aesthetic showcasing the versatility of funk music, Afro-futurism, and existence of spiritual possession. The front of the album has bright greens, reds, and blues that contrast against the black background. The image of a yellow-green possessed character is overshadowed by the hovering yellow alien-like skull. The yellow skull and the possessed character have empty black eyes and small white dotted pupils representing performance of ecstatic behavior (Wright, 2013). The artist's representation of spiritual possession on the album cover hints toward duende's mystical embodiment. On the crease of the record album (center of image), there is a woman who has been disfigured, a common trope across Funkadelic's album covers. At face value, the presence of women on Funkadelic's album covers can be assumed to resemble historical genocide, dispossession, and femicide. Using the lens of spiritual possession unveils symbolic significance of spiritual mounting at play.

Similarly,

Childish Gambino's album cover, Awaken! My Love! (on left), portrays a Black woman's

head with her eyes rolled back, wrinkling of the brows, and a mouth wide open which slightly

displays her teeth and tongue. Surrounding her face is a bright white headpiece that has become

highlighted by a blue-neon light that enhances her physical features. In contrast to Take it

to the Stage!, Childish Gambino's cover does not use alienistic characters like

Funkadelic, rather, they use a woman as the focal point on his 2016 album cover. Nevertheless,

Childish Gambino's album cover resembles Funkadelic's as they both hint toward mystical

Afro-futurity and duende's forceful possession.

Similarly,

Childish Gambino's album cover, Awaken! My Love! (on left), portrays a Black woman's

head with her eyes rolled back, wrinkling of the brows, and a mouth wide open which slightly

displays her teeth and tongue. Surrounding her face is a bright white headpiece that has become

highlighted by a blue-neon light that enhances her physical features. In contrast to Take it

to the Stage!, Childish Gambino's cover does not use alienistic characters like

Funkadelic, rather, they use a woman as the focal point on his 2016 album cover. Nevertheless,

Childish Gambino's album cover resembles Funkadelic's as they both hint toward mystical

Afro-futurity and duende's forceful possession.

In

addition, Childish Gambino's Awaken! My Love! was inspired by Funkadelic's 1971 record

cover titled, Maggot Brain. The woman on the cover of Maggot Brain (on right)

also has her mouth open, shows her white teeth, and is the focal point of the cover. The rest of

her body appears to be buried underground, similarly to Childish Gambino's album. Yet, it

appears that the two women are yelling and the facial expressions can be mistaken as if an act

of violence has occurred. On the contrary, I argue that the women are not in pain, but the act

of bellowing eludes toward an ecstatic high resulting from a mounting ceremony produced by

duende. Each cover highlights headshots of women in a moment where Orishas, deities, or what I

claim duende can seize the head initiating spiritual trance. Whether these album covers depict

futurity, the supernatural, or transcendence of mindbodyspirit, both artists' albums are

physical artifacts displaying duende's long lasting effects. Today, traces of duende's presence

can still be found in various geographical spaces (record shops, entertainment stores, homes)

and in the virtual space of the internet.

In

addition, Childish Gambino's Awaken! My Love! was inspired by Funkadelic's 1971 record

cover titled, Maggot Brain. The woman on the cover of Maggot Brain (on right)

also has her mouth open, shows her white teeth, and is the focal point of the cover. The rest of

her body appears to be buried underground, similarly to Childish Gambino's album. Yet, it

appears that the two women are yelling and the facial expressions can be mistaken as if an act

of violence has occurred. On the contrary, I argue that the women are not in pain, but the act

of bellowing eludes toward an ecstatic high resulting from a mounting ceremony produced by

duende. Each cover highlights headshots of women in a moment where Orishas, deities, or what I

claim duende can seize the head initiating spiritual trance. Whether these album covers depict

futurity, the supernatural, or transcendence of mindbodyspirit, both artists' albums are

physical artifacts displaying duende's long lasting effects. Today, traces of duende's presence

can still be found in various geographical spaces (record shops, entertainment stores, homes)

and in the virtual space of the internet.

Conclusion

Challenging our active listening practices allows us to rupture the commonly reproduced violent histories, sounds, and narratives that continue to otherize Afro-diasporic music. Once listeners comprehend how Western listening practices contribute to ongoing centuries of marginalization, then we can deeply engage with the spiritual and futuristic complexities in the music produced by funk artists. Resituating García Lorca's duende into Afro-diasporic music allows for a deeper understanding of how we engage with listening practices within music produced in the United States. Rather than assuming shrieks, grunts, and yells are mere vocal utterances, I argue that duende's supernatural powers are summoned in Funkadelic's aesthetics and transmitted into Childish Gambino's music. Musical artists like the group Funkadelic and Childish Gambino display duende's discursive power through various forms of creating music, sampling, call-and-response rituals, and are displayed in artistic symbolism on album covers that continue to be viewed in society. While many audiences may mistake duende's spiritual possession for irrationality, listeners must be conscious of reproducing what Jennifer Stoever (2016) called the "sounding Other." Ultimately, not everyone will understand the complexities of spiritual possession or duende's force, but the real question is, did you victimize the musical performances and art as the "sounding Other"? Or were you able to engage in how "non-traditional" listening practices can invite spiritual elements?

References

Assumma, Maria Cristina. (2005). García Lorca and the duende. In Luisa Del Giudice & Nancy van Deusen (Eds.), Performing ecstasies: Music, dance, and ritual in the Mediterranean (pp. 205–215). Institute of Mediaeval Music.

Bell, Pedro. (1975). Let's take it to the stage! [Album Painting]. https://ultimateclassicrock.com/pedro-bell-dies-funkadelic/

Brown, James. (1986). Give it up or turnit a loose [Song]. On In the jungle groove [Album]. UMG Recordings.

Childish Gambino. (2016). Riot [song]. On Awaken, my love! [Album]. Glassnote Entertainment LLC.

Funkadelic. (2005). Maggot brain [Album]. Westbound Records.

Funkadelic. (2015). Good to your earhole [Song]. On Let's take it to the stage! [Album]. Westbound Records.

García Lorca, Federico. (1933). Teoría y juego del duende. NoBooks. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Teoria_y_juego_del_duende/Y2_2DQAAQBAJ

García Lorca, Federico. (1944). Poema del canto jondo. Losada.

García Lorca, Federico. (2010). In search of duende (Christopher Maurer, Trans.). New Directions.

Kajikawa, Loren. (2015) Sounding race in rap songs. University of California Press.

Nava, Alejandro. (2017). In search of soul: Hip-hop, literature, and religion. University of California Press.

Rose, Tricia. (1994). Black noise: Rap music and Black culture in contemporary America. Wesleyan University Press.

Simmons, Kimberly E. (2018). Race and racialized experiences in Childish Gambino's "This is America." Anthropology Now, 10(2), 112–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/19428200.2018.1494462

Stoever, Jennifer L. (2016). The sonic color line: Race and the cultural politics of listening. New York University Press.

Vincent, Rickey. (1996). Funk: The music, the peoople, and the rhythm of the one. St. Martin's Griffin.

Wilson, Kristine. A. (2008). "Black sounds": Hemingway and duende. The Hemingway Review, 27(2), 74–95. https://doi.org/10.1353/hem.0.0001

Wright, Amy Nathan. (2008). A philosophy of funk: The politics and pleasure of a parliafunkadelicment thang! In Tony Bolden (Ed.), The funk era and beyond: New perspectives on Black popular culture (pp. 33–50). Palgrave Macmillan.

Wright, Amy Nathan. (2013). Exploring the funkadelic aesthetic: Intertextuality and cosmic philosophizing in Funkadelic's album covers and liner notes. American Studies, 52(4), 141–169.