Sylvia: This project is, you know, as we both have always said, at its core a collaboration from, you know, both of the work that Luis and I have each been involved with for, you know, over a decade. And when I graduated college, I went to work at an organization called Appalshop, A-P-P-A-L as in Appalachia, which is a media arts organization in Eastern Kentucky that was founded in 1969 in response to the derogatory national coverage of the war on poverty and was sort of an organization founded with this vision of community accountable, ethical documentary representation. And so it's, it's an organization really grounded in a vision of community documentary work. They have a community radio station, and I became—I was a VISTA there for a year and then became a producer, a radio producer for the station and eventually the director of public affairs. And that's where I learned about documentary work broadly and, and sound editing specifically; it was my first time in a studio, it was my first time using a recorder and ended up working there full time for about five years. And, during that time, one of the projects at Appalshop that I was a part of that was dearest to my heart is a weekly radio show called Calls from Home. And that radio show was founded around 2000 in response to all of these new prisons being built in the region. This is the heart of coal country, and in response to the decline of the coal industry this region has been one of the most concentrated areas of rural prison growth in the nation. And so all of a sudden within a short period of time, this tiny little community radio station was surrounded by many, many prisons, state, federal, and private, seven of which were all within the broadcast area of this tiny little community radio station.

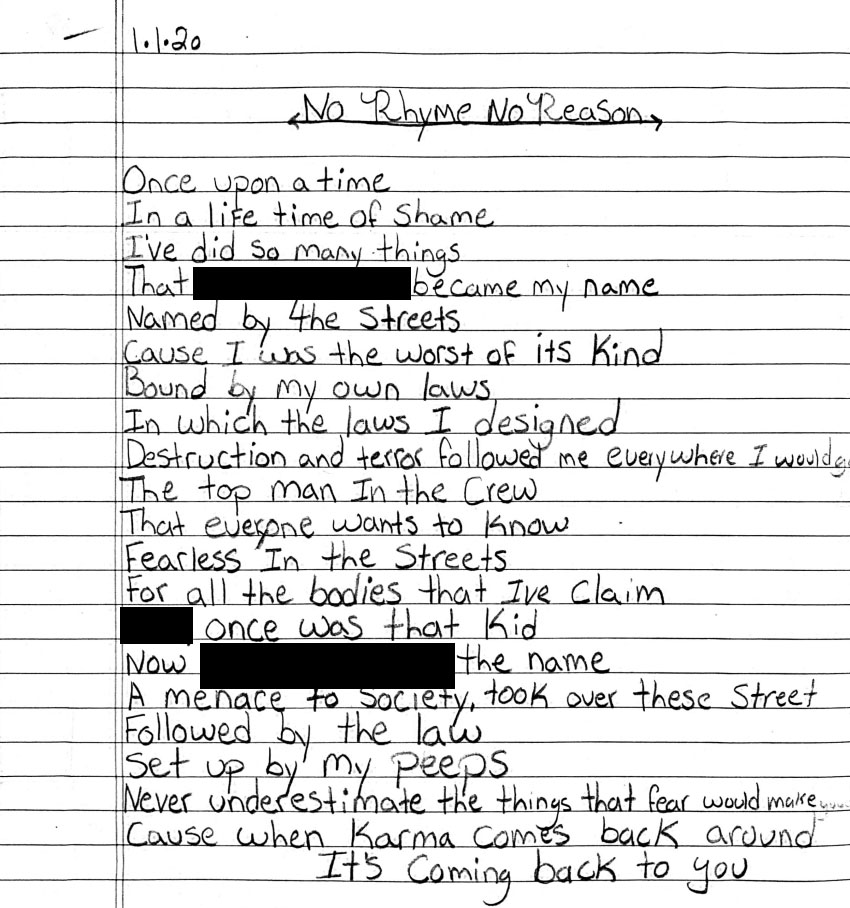

And so it's a long, incredible story of how the show began. But, in short, people that had just been sent to these prisons, very far from home, eight, ten, twelve hours away, if not further for people in the federal prisons, they started listening to the radio show and, in the late '90s, actually, started calling in to the radio show. This was before there were a lot of private prison phone contracts restricting what numbers people could call. And so they were actually able to directly call the on-air room, and there was an incredible DJ there who sort of got the show started and welcomed their calls and started this correspondence. And it was really the work of people inside who, who realized this was a point of access, and they sort of came to the radio station and had music requests and started giving shoutouts to their other fellow folks inside over the airwaves.

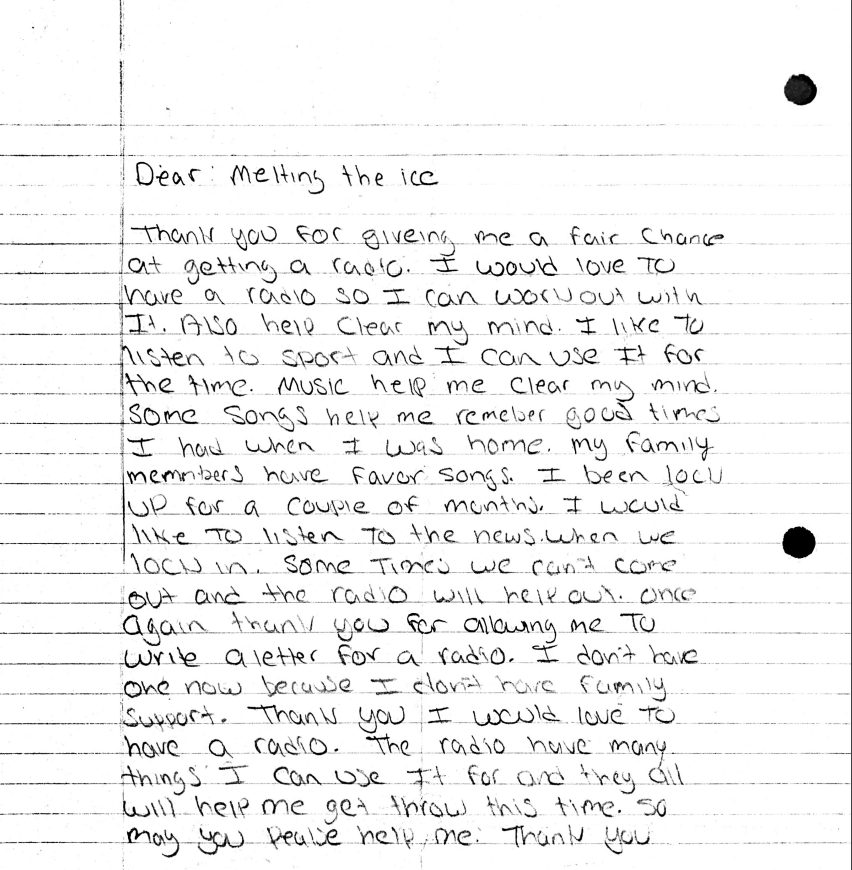

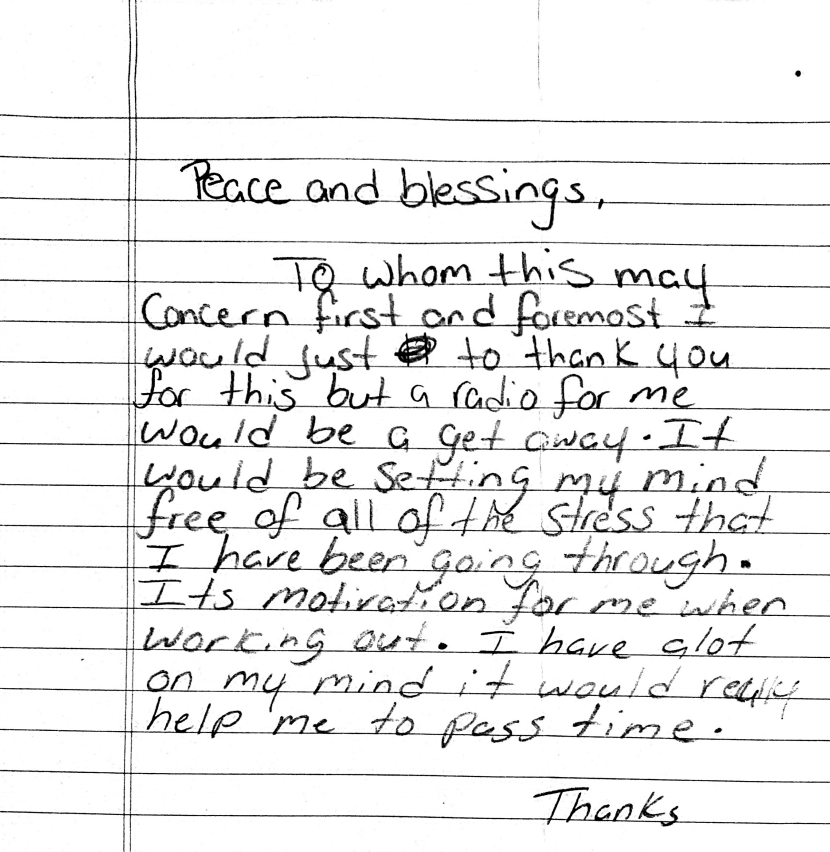

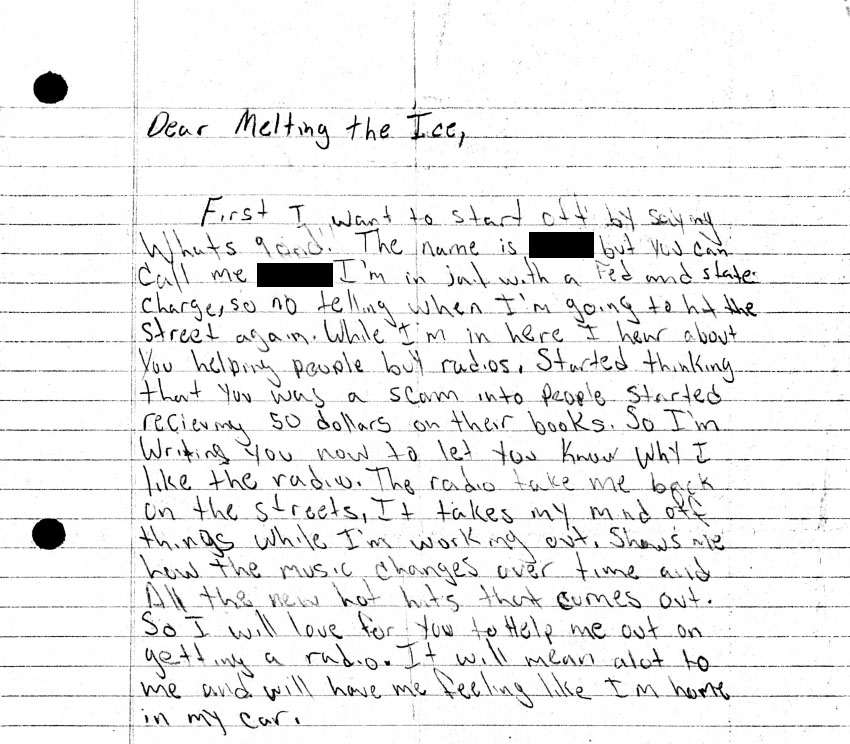

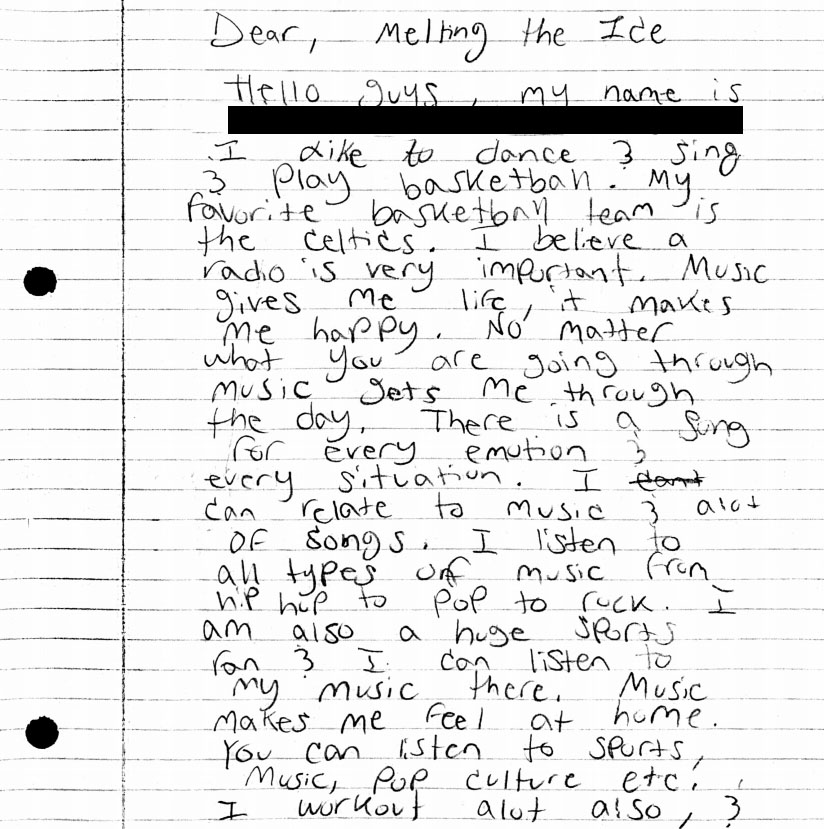

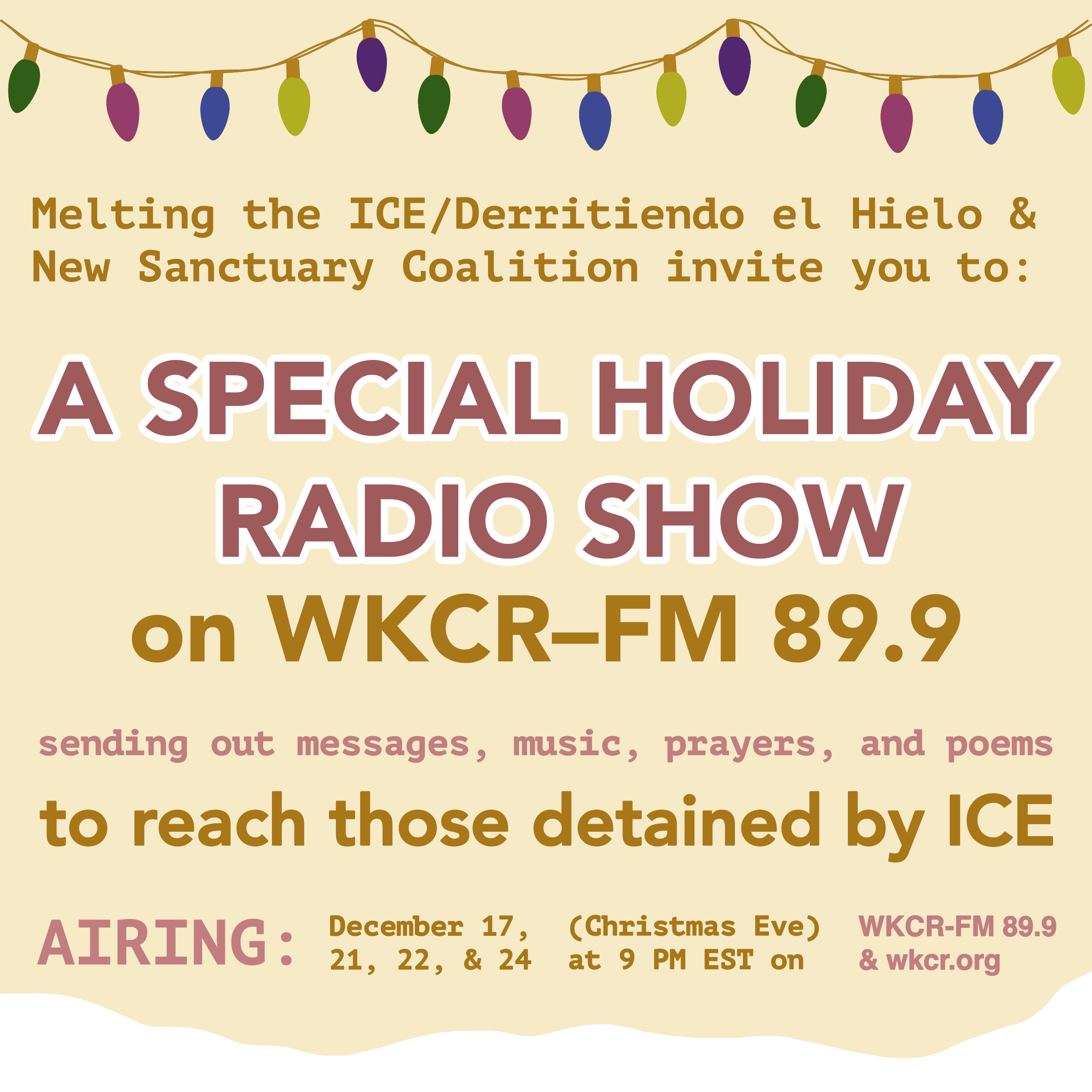

And so that actually grew into this show that now has existed for two decades that's a weekly show that sends music and messages over the airwaves to people incarcerated. And the current format of the show is actually primarily family members calling in to leave messages to their loved ones who are incarcerated. So it's, it's broadcasting those family messages and music requests out over the airwaves.

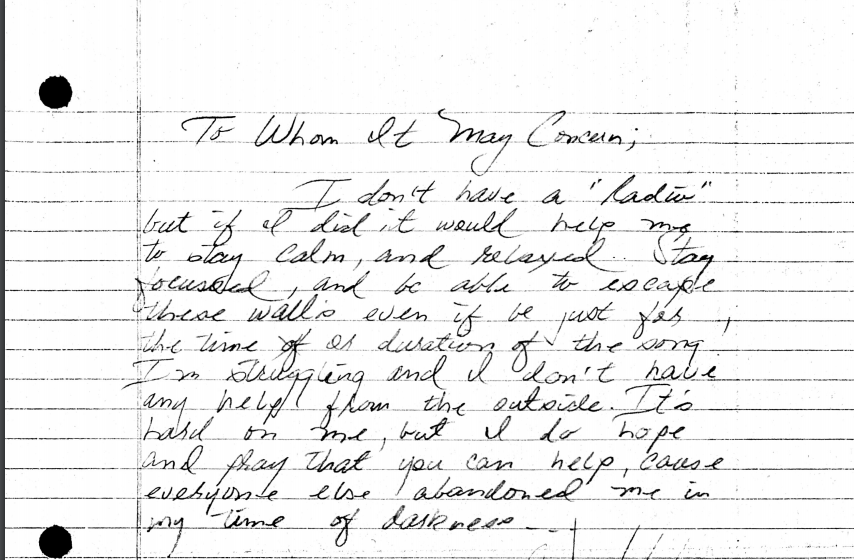

And so being a part of that show, I co-directed it for four years, and being in the studio, night after night, hearing these calls and getting to know the callers, is what taught me the power of community radio as a, as a tool to transcend these walls and build, build deeply meaningful connections that I think also then opened up space for other kinds of organizing. So, so that was sort of my own background and, and being a part of ongoing organizing work against continued rural prison expansion in Appalachia.

And then sort of skipping forward, I came to New Haven by way of New York and had done some radio work in New York, but working with folks at the Immigrant Rights Clinic at NYU that were trying to figure out ways to reach folks in detention in the northeast. And had sort of been doing a little bit of that, and then came to grad school, and then was introduced to Luis, and then everything changed, and it was really together that we conceptualized like how could we really sort of create something that is ongoing, that is sustainable, that is sort of using this idea and model of sound that we both love so much and have done so much in to think about how we could create a program that is reaching people that are currently in jails and ICE detention centers and, and prisons here in the Tri-state area.

And of course, I mean, Luis, you bring just so much of your own experience and connections and networks of, the depth of the organizing that you're a part of here. And so that's sort of where we began, I guess about a year and a half ago.

So my professor introduced me to Luis, and I called you up and you're like, "I believe in collaboration. Let's do it. When are we gonna get coffee?" And so we got coffee and sat down, and take it away.

(laughs)

Luis: Yeah, for sure. Thank you. Thank you, Sylvia. Yeah, and, you know, and before, before that point of the both of us meeting, my background: I was born in Ecuador. And when I was 13, I moved with my family to Guilford, Connecticut, to reunite with some of my other family who had left Ecuador in the mid-1990s. And I got into activism and organizing through radio. So I have been—I had been in the, in the states for 10 years. This was the summer of 2007. And I started to tune to WPKN, which is a community radio station where the programmers are volunteers and they play all kinds of different content.

And one morning, I was tuning in and I ran into the show called ¡Barricada!, which had an interesting mix of alternative music in Spanish. And the hosts often spoke about immigration reform, about how the political landscape was shaping Latin America at the time. And one day, they had a call to action; they said, "If you're listening out there, come to the May 1st march in New Haven."

Now, if we look back in 2007, it was the year before the election of Barack Obama, there was a lot of energy across the U.S. in hopes that there is a passage of some type of immigration reform. So with that energy, I went to the May 1st march; it was incredible, there was over 1,000 people there chanting for immigrant rights. And just jump forward a month, I am, I was playing pool with a friend at a restaurant/bar, and I run into this table of Spanish speakers. It's very vibrant and there's many pitchers on the table, and there's Belgium french fries and people playing pool. And then I recognized a man who gave a speech at the May 1st march. So I approached him and I, I was invited to sit down at a table and kind of chat. And we're talking about everything, mostly around social justice issues and Latin America. And I said to this man, "Hey, you should tune into this radio show. It's called ¡Barricada! and it's every other Monday at WPKN." So then he says, "Yo, that's, that's me and that's Raul and that's Ricardo."

So I was immediately invited to come and hang out at the radio station and see how they do it. So they said, "We'll pick you up at five in the morning from New Haven." And I said, "Done."

Sylvia: Luis, what year was that? That was 2000 and?

Luis: This was 2007.

Sylvia: That's so cool because the first summer I interned at Appalshop was the summer of 2008—

Luis: No way.

Sylvia: —and that was like my first time working in radio.

Luis: Wow.

Sylvia: So we both started like basically at the same moment and have been doing it since.

Luis: That's amazing. And yeah, so that's how I ran into activism because these folks that I met are, are activists and are still active and, at that moment, Fatima Rojas, who's an activist and organizer here in New Haven, she was with her daughter, Ambar, and Ambar was about two months old. Now Ambar is a, is a youth activist and she delivered the letter to Governor Lamont for the Immigrants are Essential campaign in Hartford.

The first radio show that I ever had was an overnight show from 2:00 AM until 6:00 AM, and it was called Trasnochate, which, um, which means, there's no direct translation, but is to stay over, to, to transition or to travel through the night. So that was my first year, and then about eight years ago, I started to have my, my own show, which for many years didn't have a name, I couldn't really think of a name. But now it's, now it's called Módulo Lunar, which translates to the Lunar Module.

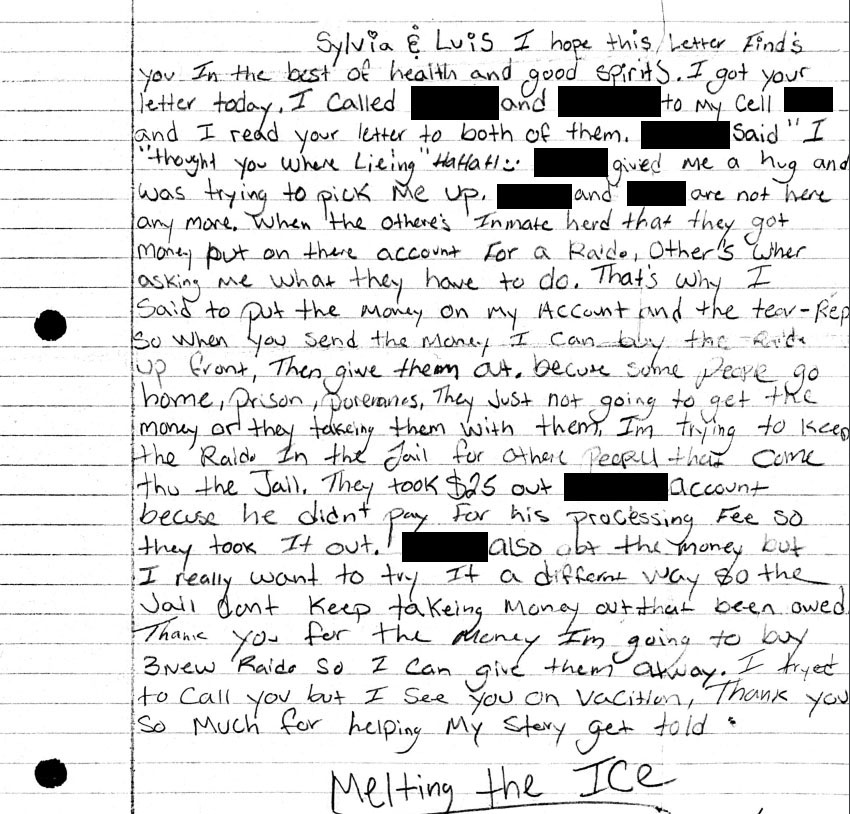

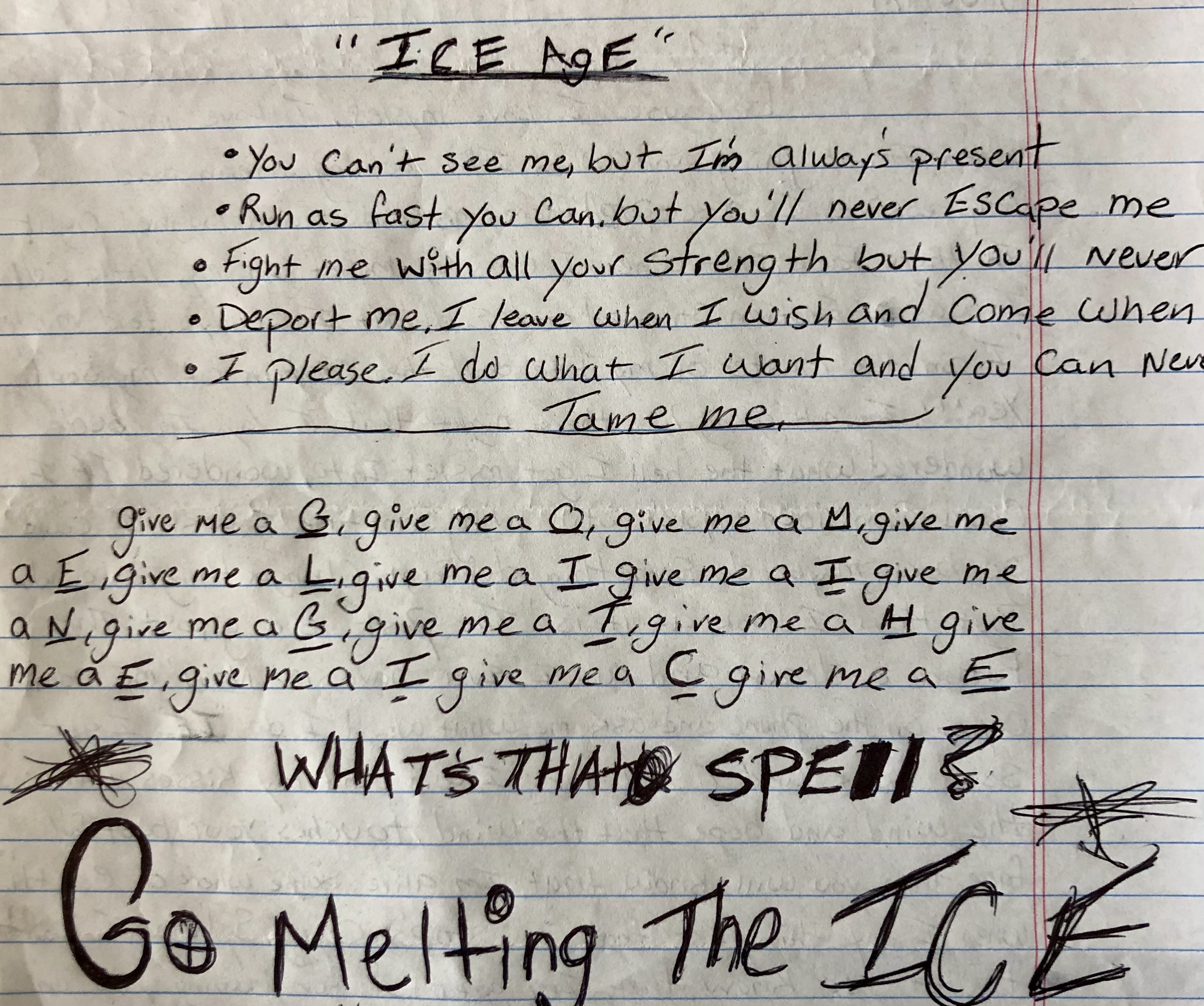

And in that space, over the years, I've brought many voices of the community for interviews and to elevate the campaigns that are happening around Connecticut in terms of immigrant justice. And then I mix that with alternative Latin American music produced all over the Americas, Europe. And that's when Sylvia and I met. We had this, this, uh, this backgrounds on, on radio and organizing, and we sat together and we said, "Hey, you know, we have this platform at WPKN, let's start there. Let's make sure that, that we identify an audience." So we saw the importance of having a show that is bilingual, and then that speaks about what is happening with immigration. And I think that, I think like, I think at this very moment, I think the idea of abolition of organizing in light of the murder of George Floyd has really opened up people's consciousness about these systems of oppression. And with a pandemic, that exacerbated sort of this opening of the veil of what the system actually is. But back then, back a year and a half ago, what we were talking about in Melting the ICE was in some ways radical. And, and that was more or less the goal, to sort of explore through a story how the system of immigration, detention, deportation works against people who are undocumented.

Sylvia: Yeah. And I think it really was this sort of joining of Luis's long history in the Migrant Justice Movement and connections here locally, and, and having your long-standing show at WPKN, and then sort of my own background coming from doing a lot of prison abolitionist work and sort of thinking about these intersections between ICE and prison abolition. We're all making these connections right now. And so how do we create a project that is, that is drawing on the strengths of both of these movements?