Our position as learners in this project afforded us a chance to

reflect, as we often ask our students to do, on the composing decisions

we made and how they influenced our learning. We try, in the dialogue

below, to look ahead to understand how our work on this project helped

us in future composing situations across media.

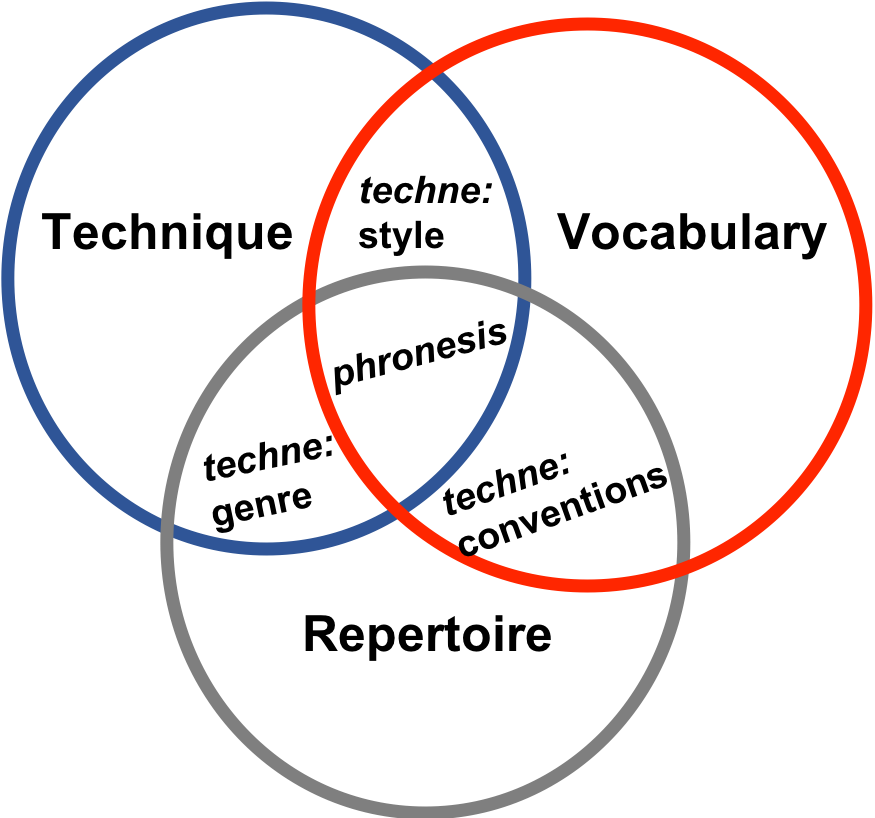

Bill: I found it interesting

that you saw my inventional work for the article—creating a kind of

heuristic as a frame for invention of the core theoretical contributions

of the article—as a new way of working for you. Could you say more

about that and describe how it asked you to practice differently, like

did it help you build repertoire? New technique? Extend your vocabulary?

Ben: One of the ways I found

the model new for me is that, like many practitioners, I never stopped

to really think about my process. I just worked. What the model invited

me to do was spend more time trying to explain what my work looks like

at the level of practice. So, for example, after writing the verse and

the chorus, I spent some time generally thinking about the arrangement

of the song. This is where I drew from my repertoire of knowledge about

pop songs in general, which tend to average around 3 minutes in length.

My first attempt was a bit longer at 4 minutes, but by playing with the

arrangement a bit, I was able to cut the first 30 seconds and then later

another 30 seconds because I sped the track up from around 118 beats per

minute (bpms) to 136 bpms. This was also partially because I began

thinking about my technique, that is, how was I going to actually play

the song? I knew it was a pop rock song, but I was thinking about pop

like R.E.M. and Pixies used to do it, and some more recent stuff like OK

GO, The Kooks, and The Fratellis… which all seemed to have more of a new

wave indie rock feel rather than an alternative rock feel, and so that

was a conscious decision to speed up the song to sound poppier. I was

then thinking both about genre and style too, as I wrote the song a half

step low on an acoustic and then tuned it to standard and sped it up

again on the electric. This last part, about the tuning, was more or

less about my vocabulary, because I recognized, once I had the song

sussed out, that I had to explain it to you, Bill, because you were

going to play on it too.

[Bill laughs]

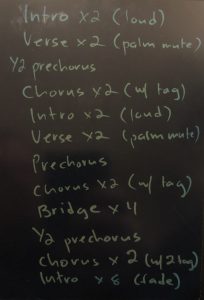

Ben: So, I have my

own vocabulary for thinking about songs when I'm writing, and it isn't

rooted in words necessarily—more like shapes, sizes, colors, and

emotions—but I realized that I'd have to find a way to explain those

shapes and colors to you. In all my previous experiences, that worked by

breaking the song down to parts like A, B, C and saying how many times

to do each part.

All this to say, I've never actually

thought about my songwriting practices so concretely. I just do them. I

just make something where the shapes, sizes, colors, and emotions seem

to fit together. I let my ear and intuition lead. The model showed me

that I have processes that are more practical than I actually thought

they were. It also showed me that space is an important part of my

practice. We chatted about this over text the other day as we were

writing.

I feel like we need a term for taking

a break as part of invention—to create enough distance that something

becomes new again. You call it a time to recover, and note it is where

growth occurs. The term we settled on, interval rest, seems to relate to

Casey Boyle's (2016) idea of "serial practice" where growth or

improvement is not necessarily linear.

How do you see interval rest

connecting to the model you developed? Did you try taking time away?

What did that time do to your understanding of the song and your ability

to write a bass line?

Bill: I take the idea of a

rest interval very literally and it comes from my experience with

athletic training where you come to understand that a workout is a way

to apply adaptive stress to your body. You are trying to subject

yourself to something that your body is so unprepared for that it will

change to be better prepared the next time.

When you see things this way, you also understand that you don't get better during the workout, you just suffer.

[Ben laughs]

Bill: You get better when you recover from it. And that takes time. And… as you get older, it takes longer too!

So, you can teach an old dog new tricks. It just takes a lot more time for the old dog!

[Ben laughs]

Bill:: For this song,

I think I did need some time off. Not so much to refine technique, per

se, but to get to a higher level of understanding than notes-in-a-row

about how I wanted the bass line to actually work. After our first

session where we tried to do a little recording, which was really still

where I was trying to figure out ideas and get a sense from you about

what I should be doing, I had almost nothing decided for sure. It was

humbling for me because I felt I might have wasted your time, but I just

couldn't go faster or try things out. I didn't have enough of any of

the three things—vocabulary, technique, or repertoire in this

particular case (with this style of pop song) to be able to improvise

and then record. So I had to work things out a bit more ahead of time.

If this were a piece of writing I would say I need a really strong

outline to work from I can't just sit down and count on a lot of

experience with the macro or micro structures of the genre to carry me

through. If it were a genre I knew more about, maybe I could have. Like

if you'd have said let's make this a funk groove or a blues, or

something, maybe I'd have had more to go on. But mostly I left that

first recording session thinking I had homework to do! Or I left that

first recording session thinking I got to get in the shed and work this

out.

Ben: One of the other

rhetorical concepts we talked about was rehearsal as an essential

component of revising. The basic idea was this: through playing the song

over and over again, we learned where it could improve or change. We

discovered its possibilities. What is your take on rehearsal as a kind

of revision process? Especially considering we just finished recording

the song and rehearsal was kind of a part of that too, right?

Bill: Yeah, well, first I

think of rehearsal as distinct from the kind of workout—practice,

whatever you might call it—that you do to create adaptations. A

rehearsal is more of a deliberate repeat, where "deliberate" means you

are engaging in doing the thing again to try to be attentive to

polishing up a performance in some way or like you were saying, maybe

trying to find a different performance. This is usually done with a

future performance in mind: a specific time, place, audience, etc. For

recording I guess it is a future audience. Practice is not always like

that. Sometimes I practice to create that adaptive stress, not with any

specific performance in mind but to change my body in a way that will

make a future performance possible.

So, can I ask you another question about this whole composing experience?

Ben: Yes, of course.

Bill: Because it is

fascinating for me. When it comes to making the song, which, you know

I've never done, I want to ask you… I felt like I was working at the

very edge of my ability, like all of the time, in all of the model's

areas: technique in terms of performance, trying to get that right, but

specifically performance for recording, not making a lot stray noises,

and then all the decisions that comprise the techniques of recording

were completely new. I was working on repertoire in terms of pop songs

of a certain era ('90s-ish), and then vocabulary which I could fill a

page describing. But what I want to ask you is what if anything, do you

feel like you might have learned from this particular process? And did

you set this challenge for yourself in order to try learn something

specific?

Ben: Well, I used to think that

when I wrote music I worked exclusively in and with sound. Now I would

think of myself as a practitioner of sound, so to speak, but you know I

was a musician more or less, and that's how I felt most comfortable,

picking up an instrument and playing and seeing what would happen. Today

I realize that's not entirely true. Much of what I make relies on other

kinds of genres, a lot like professional writers. Like the project

managers I've studied, for example, some of those genres people will

never see because they are part of a staging process. All the

spreadsheets. The to-do lists, you know. The different kinds of boards

they assemble to make sure that we can visualize work. That is all a

part of a staging process, and for me, this is the kind of visualization

of the song that I made for you.

Bill: Oh yeah, so I could figure out the parts.

Ben: Right. And in your work

with Mark Zachry and Clay Spinuzzi (Spinuzzi, Hart-Davidson, & Zachry, 2006), you called these "helper"

genres, texts put together to help someone do their job. I actually

think those helper genres are no less powerful than the target genres,

or in this case, the song. I needed all those helper genres to make the

song a song. So I'm doing a lot more writing of words on a page and

mapping of concepts visually than I ever really considered.

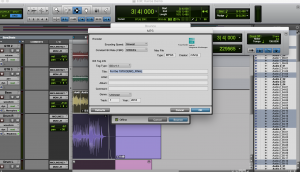

I also didn't realize how quickly I

toggle back and forth between technologies that help me visualize the

song that I'm writing. So songwriting is already a visual process for me

because I "see" the music so to speak, but spending so much time

thinking about how a smartphone and a computer visualizes sounds, and

how much those visualizations contribute to my decision-making, was

startling. For example, the first version of the song being 4 minutes

and knowing that I wanted to cut that down to 3 minutes or 3 minutes and

30 seconds… The computer told me that—it told me that it was 4

minutes long—it wasn't my ears. I may need to think about whether or

not that's a good thing at some point. And then, seeing how the drums

line up with the bass and guitars, how hand claps and vocals live

together and occupy the same sonic space, and how the digital audio

workstations literally visualize that for an author shows me that no

matter what, sound is always made somehow visual for us—whether by

associating it with records, CDs, playlists, mixtapes, or the printing

of soundwaves on our screens. Even the file name of an MP3 is a kind of

visualization.

So, I'm curious, Bill, how you might

respond to this same question. What do you feel you might have learned

from this particular composing process?

Bill: Oh [Laughs]

Ben: And did you set this challenge for yourself in order to learn something specific?

Bill: Ugh, I

feel like learning overload, I feel like almost everything I did in

making my part of this song is a new lesson, and I really only

contributed a small piece. I'm a little overwhelmed by it, in fact. In a

good way. So I'm not quite sure I really can say all the things I have

learned just yet. But one thing I realized yesterday as I finally got

what I felt like were all the parts of the bass line worked out so that I

could repeat them is that every other time I'd learned a song, I had an

existing song to reference and it acted as a really strong scaffold to

my practice. So I could say "well, there are three bits I have to get

under my fingers: the verse, the chorus, the bridge—whatever" and then

I'd go pick one, listen to that, and start working out how I wanted to

play it on the fingerboard. You know I had some choices but it was all

laid out for me already.

Here, I didn't have that. And, I

mean, first I had to decide how many parts there were and then I had to

figure out, based on the song demo you'd given me to work from—which

had, like, drums and guitar and later the vocals—what I wanted to do.

All of the parts were in flux while I was trying to learn them, and so

the only place the bass part really existed was in my own head! And that

was continuing up until the minute we recorded it.

So, I'd play it one way and kind of

like it or not, and then maybe try something different the next time

through. What I eventually did is if I hit on something I wanted to do

that was at the level, vocabulary-wise, of a note or a phrase I wrote a

few of those, what I would do is I would write them down, make a visual,

so as not to lose them because otherwise I would forget it the next

time through. And I wasn't writing notes like notes on a staff, I mean I

could have done that, but I was writing the letters or a little note to

myself like "descend minor scale from D on the A string"—so I'd just

make a little note right there when I was figuring out "what did I like

about what I played?""

So, the first breakthrough for me

that I would say in terms of learning something was actually something

you had reminded me of a long time ago when we were first working on a

different piece that we wrote and that was the way other songs can be

inspirations without having to be kind of direct quotes, and I realized

the key center of the song and the tempo were close to "Don't Stop

Believin'" by Journey. And so, just for a lark, I played the scratch

track for Leslie at home, and instead of playing the line I'd been

working on I played the Journey bass line just to show her and she

laughed about it. But then, that made me see that I could outline the

chords in the song like a bass player is supposed to do, but I didn't

have to make just a boring pentatonic box—oh and there is another

visual, right? Box on the fretboard.

Ben: [Laughs] Right.

Bill: I could make a

little melody line with more movement than that. So that's how I found

that intro bass riff that I think now becomes a little motif in the

song. And a similar analogy led me to the descending line in the chorus,

except it was "I Want You Back" by the Jackson 5, which has a

descending line in the chorus of it's song too.

Ben: So while you weren't learning other people's songs, you were using other people's songs to make your own!

Bill: Yeah, like I was

thinking about it, and going "Oh you know that descending line might

sound good here." I mean it's a completely different key, different

tempo, nothing really is the same about it except that going down the

scale sounded like an interesting complement to what you were doing

vocally and what you were doing with the rhythm track.

Ben: Right!

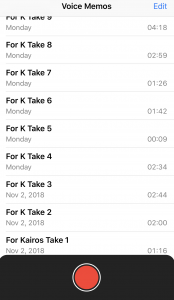

Bill: So I want to come back to this learning bit because I'm

fascinating by another thing that you said when we were texting back and

forth, and we were sending these clips—voice memos and so forth. You

noted that the venn diagram that we made for the learning model helps

you to envision the pathway to learning and composing as a kind of

spiral through those various areas.

Ben: Yes!

Bill: And for me, this invoked

a foundational idea in composition studies, really, and in design too,

when you think about it, or UX and that is the idea that the composing

is a recursive process. I haven't really dwelt on the idea of recursion—of a thing recurving back onto itself—as a visual metaphor, but it

certainly is one! So, do you think that it is important to have

something to spiral towards? When we are thinking about learning? Or is it

enough to spin endlessly through those circles or do you have to work

towards something like we did here with the song?

Ben: I think as a metaphor for

learning, spiraling makes more sense to me than scaffolding, even

though I imagine that I do, and I did, in this particular project, both.

One thing I did see is that I tend to separate the song from the

performance of the song, so I suppose I see spiraling to have an end

when you're saying, okay I'm done writing a song, and now that song is

written. At some point you have the components and you just say I'm

gonna call this song good, and move on. But, for me, the performance of a

song is a very different inventional process. Take for example Leonard

Cohen's "Hallelujah," which is an amazing song, but the performance of

it by Jeff Buckley really stuck with me a lot longer than the original

recording by Cohen. The song was the song, with verses, chorus, melody,

time signature, chord progressions, etc.… but the performance of

those elements can vary.

In writing, I think we can do

something similar by separating our ideas from the performance of our

ideas. I think over time we learn to perform ideas better, or that we

have a particular kind of performance we feel better executing. We call

these "moves" or rhetorical moves. In other words, our first take is

rarely our best when we're recording. In this way, I see writing as

largely performative. Sometimes ideas are good, but the performance

isn't right. Sometimes the performance is right, but the ideas are

lacking.

I suppose what I'm getting at is that

we spiral towards some sort of conclusion or ending, but that's mostly

arbitrary in my experience. We continue to refine how we define our

ideas over time as we learn how to perform them for different audiences,

purposes, and situations. And we do that through rehearsal while we are

inventing or discovering ideas, but also while we are thinking about

how to perform the ideas for others.

So, you had some good ideas, Bill, on

how this translated from writing music to composing more broadly.

Explain how you saw this connection.

Bill: Well, I have to credit

you for showing me that it seems now obvious in retrospect… that, you

know, in my life I do write and rewrite the same idea in order to

increase my own understanding of it. I suppose that has always been true

but it was never really very obvious to me. I want to say one more

thing about the song before I go back to this idea about how making the

song reflects on how we learn to compose, but the thing about the song

that I want to say is it does feel to me now like we wrote a song,

although that wasn't true yesterday.

Ben: [Laughs]

Bill: And its also not necessarily true that I feel like we've ever performed the song…

Ben: [Laughs]

Bill: … because we haven't sat

together in a room while you are singing and I'm playing and you're

playing and we've performed it. So it's weird to think about how yeah we

wrote a song but we never performed the song. Maybe that, to a

musician, that's a natural idea, but it's kind of a new concept for me.

But here's one thing that's really true is that it did change my

vocabulary for writing songs, so now I think it's a little more

reasonable that I might one day write a song. Because

building vocabulary, for me, means more than just learning new words or a

new notes or a new kind of scale. It also means consolidating smaller

bits into larger ones and making those available to yourself as

compositional tools. So words and sentences and paragraphs, for

instance, become "sections" of an academic argument, these rhetorical

moves that we can use to lay out a macro-structure for an argument and

that will move the dialogue forward in a given academic discussion. So,

these are the moves you are talking about and we use them all the time

as experienced writers, we're like "We'll do this, then we'll do that…"

We don't strategize about every word we put on the page, though. We'll

say, "We'll have a little lit review here and then we'll go to add a

methods section there."

We do this visually, by the way. Or

at least we use visual formats to facilitate these acts of consolidation

and transposition, is what I want to call them. Think of an outline or a

wireframe, for instance. I could pass you that on a document and it

would function as a kind of gestalt (see Hart-Davidson, 1996), so

you could be like, "okay I'll take this section and you take that

section," and we've done that when we've written other stuff.

Ben: Right. That's true.

Bill: So, for example, how

does this apply for music though? I think notes become larger structures

like chords, chords become chord progressions, and then you can use to

invoke whole genres such as the blues. So, you can learn to play the

individual tones in the minor pentatonic scale on a guitar, it's often

the thing we learn first because its pretty simple to just—every other

fret in a box shape, and we can consolidate those over time by

associate them with a shape on the fretboard. You talked about composing

songs before and thinking really just about shapes. It's a little like

Tetris. When I was first learning I was like "oh this is Tetris." An L-shape or a T-shape or whatever. The ability to move that shape to a new

location or a new key means we can use not just the notes but the whole

scale as an element to compose with in a chord progression or a pattern

like the 12-bar blues and we can play the blues starting with any key. A

musician need only shout out "Blues in G" and we know this means we

have the notes of the minor pentatonic scale, with an emphasis on the

flat seven in each key to work with and then we'll move from the key of G

for four bars, on to C and then to A. And that's because we follow this

I, IV, V progression that is the blues. And that twelve-bar pattern becomes

another vocabulary element all by itself that consolidates rhythm and

melody and establishes when the key changes happen and in what order and

all that stuff, and we can get it all just by saying "Let's play the

blues" and I don't even have to tell you that, and you know at the end

will come a turnaround, right? The signature little bit that always

comes at the end of that twelve-bar phrase. I can get all that just by

saying "Let's play blues in G."

So, any of these things can be called

out as compositional elements. That's what I mean by your vocabulary

developing. If I say, "hey folks, let's play the ascending line on the

turnaround the first time through and then we'll let the guitar play the

descending line the second time through." So then we can talk about

variations and that's all because they are in our vocabulary in a

different way. We're not thinking about tiny little bits, but we are

thinking about whole patterns. So, that's what's pretty amazing to me is

at this level, I think, especially with this song, you were working at

that pattern level. And I felt like all the way along I was running

behind as fast as I could note for note, one note at a time.

Ben: Right, right—that makes

total sense to me. I think, you know, one of the things I find kind of

interesting, kind of reflecting back on it now too, is how much of those

patterns occur in basically any genre of music. You are talking about

the box pattern, and when I was writing and choosing chords, and I was

using power chords, I wasn't thinking of the scales, but I was thinking

"oh naturally this chord follows this" because that's what fits the

pattern. Right? Similar to when you are making a list in a document.

Right? In which case you are trying to visually design information in a way

that makes it easily digestible. Right? And so, I see myself drawing

frequently on those patterns even if I'm not stopping to go "Oh I'm

using a pattern here. Or I'm using this move." It's just I understand

that that's one of the moves that can be made.

Bill: I think the revelation

for me—the first visual-auditory connection when I started learning to

play the bass was this notion that you can have a chord in a

single-voiced instrument like I learned on a saxophone. I was only ever

one note on a chord. Playing the guitar you have these notes laid out

for you on the fretboard, and all of a sudden a chord isn't just three notes

it's a shape and you are like "Ohhh." And the cool thing is changing

keys before with a single-voiced instrument was always a pain because if

I'm in the key of C, concert C is great. No sharps, no flats. That

means every note you're going to play the natural version of that note.

But then if you start changing that around all of a sudden I've got to

transpose in my head and move things up and down. Or I have to play all

these notes—even in musical notation they are called accidentals. And

that's because what you can do pretty easily on the fretboard or on the

keyboard of the piano which is just slide your hand over one little bit,

takes mental gymnastics on the saxophone.

["For the 1979" outro fades up]

Ben: Here is where we end our

reflection—for now. If you haven't already, we invite you to listen and

respond to other parts of this webtext. We hope that you found our

orientation to learning as demonstrated in the model useful for your own

composing practices.

["For the 1979" outro fades out]