Although writers and scholars have often looked at the working class, they have generally focused on the values such workers exhibit rather than the thought their work requires—a subtle but pervasive omission. Our cultural iconography promotes the muscled arm, sleeve rolled tight against biceps, but no brightness behind the eye, no image that links hand and brain. (Rose, 2009)

SIZE UP: LITERACY AND FIREFIGHTING

This webtext extends work that grew from a personal realization I had while completing graduate studies at the University of Rhode Island. At the time, I had been a member of the fire service for over a decade, but I didn’t see the work I performed as a writing teacher and scholar as something that was connected to the work I performed as a firefighter. That changed one summer when I picked up Beverly Sauer’s (2003) The Rhetoric of Risk on the recommendation of a professor. Immediately, I realized that firefighters, like the miners Sauer followed, made extensive use of embodied knowledge while operating in uncertain, risk-laden environments. It was an exciting, transformational moment for my development as a literacy scholar, as the text prompted me to reflect on my practice and attend to the epistemic, knowledge-producing practices embedded in firefighters' work—practices like sounding a floor to determine if it is safe by striking a floor with an axe or reading smoke to draw insights about the location and intensity of a fire within a building.

Yet, another question became palpable: Why had it taken me this long—as someone who had read a substantive amount of scholarship on literacy and multimodality—to see these practices for what they were? Why had I, as both a literacy scholar and firefighter, failed to perceive knowledge production and communication as mission-critical elements of firefighting? As I continued to reflect on the implications of this realization, I became even more troubled. Sauer’s (1994, 1998a, 1998b, 1999, 2003) studies of the mining industry had made it unmistakably clear not only that miners leveraged embodied sensory knowledge to safely assess and negotiate hazards in uncertain work environments, but also that the industry had largely failed to recognize the critical role that these practices have with and for safety and health outcomes.

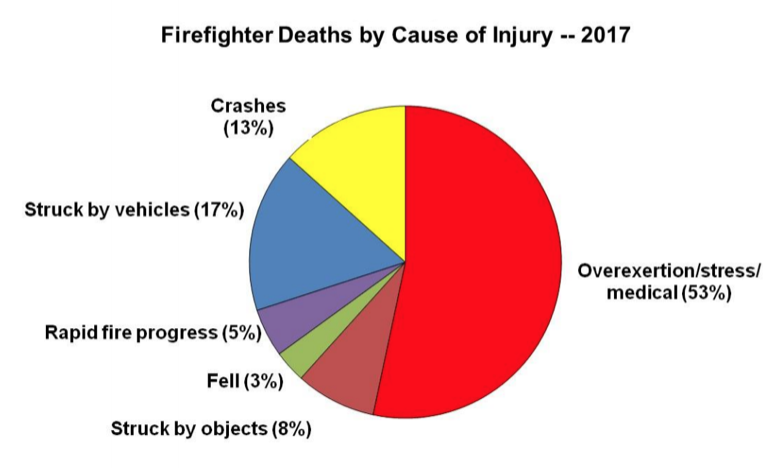

Motivated by and equipped with this understanding, I turned toward the task of exploring how discourse disseminated by major fire service organizations framed the connections between literacy and firefighter safety and health. For instance, after analyzing the publicly viewable data that the United States Fire Administration (2018) collected on firefighter injury and fatality through the National Fire Incident Reporting System (NFIRS), I learned that NFIRS utilizes nine codes for classifying cause of fatal injury defined in NFPA 903: Uniform Coding for Fire Protection (National Fire Protection Association, 1981). Factors associating firefighter literacy practices with potential connections to injury and/or fatality—decision making, risk assessment, communication breakdowns, lapses in situational awareness, information sharing—were conspicuously absent from the list of codes available for classifying causality (for more, see Amidon, 2014).

What I want to emphasize here is that methodological choices for standardizing how cause of injury is reported not only influence which data enter NFIRS, but more importantly influence the types of inferences members of the industry might draw regarding the type of hazards firefighters most commonly encounter within their work. NFIRS data are created by reporting parties who must consider the factors surrounding a fatal event and interpret which of the nine codes they should enter into a form field. While reporting parties might seek to list or describe other causal factors, the NFPA 903 coding framework and NFIRS reporting forms rhetorically constrain reporting parties by limiting and standardizing the causal codes they might choose from. These choices can have a monumental impact on the kinds of visualizations that might be made downstream, as data visualizations draw from and represent trends in aggregate data and are, of course, key information sources for making and justifying a range of decisions, actions, budget allocations, and more.

One notable example of this phenomena can be seen in the annual reports on trends in firefighter injury and fatality that the National Fire Protection Agency (NFPA) promulgates. Take for instance, "Figure 3: Firefighter Deaths by Cause of Injury," a data visualization that recently appeared in the NFPA’s Firefighter Fatalities in the United States 2017 (Fahy et al., 2018, p. 21). Note that this visualization indicates that over half of firefighter fatalities are due to "overexertion, stress, or medical [events]." Based on the visualization, audiences might infer that firefighters are exposed to levels of heat and stress that human bodies may not be prepared to withstand or that events involving vehicles ("crashes" and "struck by vehicles") accounted for 30% of firefighter fatalities in 2017. Still, the element of this data visualization that I find most striking is that a whole subset of causal factors are simply absent: lapses in situational awareness, miscalculations in decision making, poor risk assessment, breakdowns in communication, and insufficient information sharing do not appear as causal factors of fatal injuries. Again, this is because the visualizations draw from data in NFIRS that suggest cause of injury occurs proximal to the moment of firefighter fatality, failing to account for the more distal epistemic, communicative, and/or operational practices that might give rise to hazardous working conditions in the first place.

In comparison to the limited set of factors for reporting causality in NFIRS, comprehensive investigative reports that include event narratives—reports that offer space for more expansive analysis and discussion of the events surrounding firefighter fatalities—commonly point toward human factors. For instance, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) routinely identifies communication breakdowns, lapses in situational awareness, and decision making as "contributing factors" in the after-accident reports the organizations produces through the congressionally mandated Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program (FFFIPP) (e.g., NIOSH, 2010, 2013a, 2013b). Similarly, the U.S. Fire Administration periodically disseminates technical series reports, which have also indicated that decision making, information exchange, and communication play a role in incidents where firefighters sustain fatal injuries. In fact, one report in this series, Special Report: Improving Firefighter Communications, not only found that "little attention [had been] paid to human factors" but also observed that "a dearth of available literature pertaining to the impact of human factors on effective fireground communication" exists (Thiel, 1999, p. 2).

Since that report, a number of researchers have forwarded scholarship that appreciates the critical role that literacies play within fire and emergency medical service organizations. For instance, Margaret Somerville and Anne Lloyd (2006) observed that firefighters and other blue-collar workers "learn to work safely from embodied experiences in the physical environment of the workplace and interactions with more experienced workers" (p. 287). Ronald Timmons (2007) argued that emergency managers seeking to engineer solutions to systematic communication breakdowns often turned toward technology, rather than considering the way that suppressed emotions, cognitive bias, and sensory overload contribute to decision making and communicative performance during disasters. More recently, Elena Gabor (2015) posited that "cultural norms" such as stamping down emotion or dampening the severity of a situation within radio communications have contributed to fatal misunderstandings. Indeed, a host of scholars—such as Sarah Moseley (2017), Andrew Ishak and Elizabeth Williams (2017), and Elizabeth Angeli (2015, 2018)—have recently attended to the practices fire and emergency services personnel mobilize to construct knowledge, identify hazards, evaluate risks, set priorities, plan and coordinate work activities, or communicate and exchange information. Still, I would argue that the fire service at large continues to wrestle with the very blue-collar "cultural iconography" that Mike Rose (2004, 2009) has described. In this section, then, I briefly situate how this webtext resonates with three strands of scholarship on multimodal literacy, as this work has shaped the methodological and designerly decisions I’ve made in this visualization project. I close this section by articulating developing methodological tools that render blue-collar literacies visible and arguing for the ways in which these literacies matter and should matter to writing studies scholars.

MULTIMODALITY: CLASS AND LITERACY

Following early work in writing studies that explored the ways that literacies were practiced and valued in community (Heath, 1983), nonacademic (Odell & Goswami, 1985), extracurricular (Cushman, 1998; Gere, 1994), and workplace contexts (Hull, 1997; Spilka, 1993; Sullivan & Dauterman, 1996), scholars began to account for the ways that these locations inflected practice. From a methodological perspective, Anne Ruggles Gere (1994) observed that this work demonstrated "the need to uncouple composition and schooling, to consider the situatedness of composing practices, to focus on the experiences of writers not always visible to us within the walls of the academy" (p. 80). In turn, scholars such as Rose (1989; 2004), Sauer (2003), Dorothy Winsor (2000), Julie Lindquist (2002, 2004, 2007), and William DeGenaro (2001, 2007) forwarded inquiry into blue-collar and working-class literacies. Lindquist (2004), for instance, argued that although the field "is concerned with problems of adult literacy and [educational] access," it has also fallen short of appreciating "that 'class' names a social reality that indexes rhetorical practices and predicaments" (p. 190). Winsor (2000) posited that the literacies blue-collar workers utilized in a manufacturing facility were generally undervalued and overlooked by members of the corporation. Reflecting on this discovery, Winsor asserted that "the social systems in which blue-collar workers function may be one of the factors that leads to their being considered less literate than are white-collar workers, because opportunities for and definitions of literacy reflect the work of the dominant group" (p. 181). Indeed, Lindquist's and Winsor's positions resonate with statements Rose (2004) has forwarded regarding the types of associations Americans often make about the relationship of blue-, pink-, and white-collar work and the intelligence of workers:

These limiting categories reaffirm longstanding biases about particular occupations and cause us to miss so much: The mental processes that enable service. The aesthetics of physical labor. The complex interplay of the social and the mechanical. The choreography of hand, eye, ear, brain. The everpresence of abstraction, planning, and problem solving in everyday work. (Rose, 2004, p. xx)

The methodological insight I take from these scholars, then, is that rendering visible the literate practices firefighters marshal to coordinate activities, assess risk, select strategies and tactics, and/or communicate while working destabilizes the ways "discourses [that define class experience] circulate" (Lindquist, 2007, p. 273).

MULTIMODALITY: MATERIALITY AND EMBODIMENT

One aspect of class that has a powerful shape on firefighters' literacies—and blue-collar literacies more generally—is the way that their working environments materially inflect their reading and writing practices. Today, a rich strand of scholarship in writing studies surrounds the nexus of materiality, embodiment, and situated literacy, including Jack Selzer and Sharon Crowley's (1999) Rhetorical Bodies; Mary Lay's (2000) The Rhetoric of Midwifery; Christina Haas's (1996) Writing Technology; Sauer's extended inquiry within the mining industry (1994; 1996; 1998a; 1998b; 1999; 2003); Angela Haas’s (2007) "Wampum as Hypertext"; Cynthia Selfe’s "The Movement of Air, the Breath of Meaning: Aurality and Multimodal Composing"; and Jody Shipka's (2011) Toward a Composition Made Whole.

Still, leaders in this area continue to issue calls for members of the field to more carefully attend to this nexus. Christina Haas and Stephen P. Witte (2001) asserted that the field "ha[d] yet to attend systemically to the embodied nature of writing" (emphasis added, p. 414). Selfe (2009) suggested that the field has been slow to recognize and value the degree to which all forms of literate practice have an multimodal dimension. Shipka (2011) has observed that "the challenge [our field faces is] one of finding ways to attend more fully—in our scholarship, research, as well as our teaching—to the material, multimodal aspects of all communicative practice" (p. 21). I would add that as writing studies continues to recognize that embodiment matters for literacy we will also need to attend, more carefully, to the question of how embodiment matters for literacy across contexts. Indeed, the material, social, and cultural variability of contexts where literacy is enacted means that various locations are laden with distinct opportunities and risks. To put a finer point on it, embodiment carries distinct material consequences for miners and firefighters and waitresses than it does for engineers and technical writers and bankers.

MULTIMODALITY: CULTURES AND COMMUNITY

Indeed, this is the very point that I believe Selfe, pointing directly toward to earlier scholarship by Keith Gilyard (2000), Patricia Dunn (1995, 2001), Jacqueline Jones Royster (1996, 2000), Bernard J. Hibbitts (1994), Malea Powell (2002), and Scott Lyons (2002) calls for when asking members of writing studies to consider the implications of positioning "print literacy" centrally within the field:

The almost exclusive dominance of print literacy [in our classrooms and scholarship] works against the interests of individuals whose cultures and communities have managed to maintain a value on multiple modalities of expression, multiple and hybrid ways of knowing, communicating, and establishing identity. (Selfe, 2009, p. 618)

Continuing, Selfe (2009) argued that members of the field need to "develop an increasingly thoughtful understanding of a whole range of modalities and semiotic resources" (p. 618), while underscoring a warning that Lyons (2002) and Powell (2002) had forwarded. Namely, recirculating uncritical and reductive representations of cultural groups' practices of literacy causes material harm and can perpetuate cultural erasure. A key point that I see Selfe, Lyons, and Powell articulating, a point I want to underscore, is not that we should privilege a multimodal-, embodied-, aural-, alphabetic-, or print-based approach toward literacy, but rather that we have responsibility as literacy scholars and educators to be respectful of and attentive to the ways that individuals and groups draw from a wide variety of semiotic and cultural resources when enacting literacies in situated locations. Culture, economics, and history, in other words, have a profound material impact on how embodiment matters in specific locations

In terms of how this connects to my work with firefighters’ workplace literacies—a community that honors blue-collar values and traditions—I've found this insight particularly valuable for reflecting on how decisions I make as a researcher impact my stance (Amidon & Simmons, 2016; Grabill, 2012). That is, I see this insight functioning as a kind of methodological check that reminds me to consider whether the representations of firefighter literacy that I construct are sensitive to the tactile, kinesthetic, aural, and visual dimensions of firefighters' literacies as well as the ways that these workers leverage alphabetic-, print-, and screen-based literacies to scaffold and organize work. Firefighters have not only developed practices for reading smoke (Dodson, 2005) and fire behavior (Raffel, 2011), but have also composed national standards, blogs, training manuals, union charters, memos, and trade magazines, as well as curated vibrant social media communities on Instagram and Twitter to scaffold and organize their work. Methodologically, my intent is to be sensitive to the ways firefighters mobilize an array of literacy practices while working as individuals and collectives within discourse communities that are socially, culturally, and historically situated. It is my hope, then, that the visualizations I've selected for this are understood as partial and incomplete distillations of the ways a small number of firefighters practiced and/or described practicing literacy.

VISUALIZATIONS MATTER

Taken together, these strands demonstrate that over the past 20 years writing studies has grown increasingly aware of the semiotic and material richness encircling literate practice across cultural, geographic, contextual, and historical locations. Despite this growing awareness, literacy continues to be understood narrowly in many contexts as an alphabetic, text-based activity, which Selfe (2009) has argued, "constrains the semiotic efforts of individuals and groups who value multiple modalities of expression" (p. 616). Broadly, it matters which, whose, and how literacies are represented and depicted within scholarly, civic, and workplace discourse, because these representations illuminate "the role of language in processes of resistance and dissent as well as its capacity to articulate and affirm cultural traditions" (Lindquist, 2007, p. 275). Placing the spotlight squarely on what and how literacies mean for blue-collar work not only reveals the critical role that literacies occupy within these contexts, but also underscore the complex and dynamic experiences that humans have with literacy across class (LeCourt, 2006; Rose, 2004). As Donna LeCourt (2006) posited, critically attending to how we represent literacy can work to destabilize "a dichotomous relationship where one discourse is depicted as in almost complete opposition to another" (p. 30).

Developing methodological tools that render visible the kinds of literacies that commonly unfold within blue-collar work as tacit, unseen, or taken-for-granted elements of practice is important because it invites scholars and practitioners to reconsider how sense-making, communication, and interaction mean for work more broadly. They illuminate, as LeCourt (2006) put it, the "particular social relations" and "social positions" (p. 45) that surround the intersections of work, class, and literacy in situated classes. Indeed, Lew Caccia (2007) observed that blue-collar workers are subjected to hazards at such disproportionate rates that "exposure to risk could be thought of as a cultural marker that contributes to the construction of working-class ethos" (p. 164). This point is made even more alarming when considering that blue-collar workers often labor within "work environment[s] that featur[e] unequal knowledge distribution” and “a lack of opportunities for decision making" (Hoover, 2007, p. 35). Raising the visibility of blue-collar literacies matters because it could engender positive health and safety outcomes for individuals working in the very occupations that are most vulnerable to workplace injury and fatality.

Perhaps the greatest value of the visualizations forwarded in this webtext is that they begin to sketch some of the complex relationships present within the activities firefighters perform while working as individuals and collectives on firegrounds. In particular, I have selected images, video, sound recordings, tabularized data displays, and interactive network visualizations—a broad set of visual and extra-visual data—that illustrate the richly networked and multimodal literacies that firefighters mobilize to coordinate distributed work. It is my hope that identifying examples of these tacit practices opens them up for broader discussions about how these practices might be leveraged, refined, or eschewed by members of fire departments who confront rhetorical situations in distinct localities. It is certain that other firefighters in other locations use practices that are distinct because they have grown from different traditions, histories, materialities, and economies. Still, illuminating these practices creates opportunities for firefighters, company officers, and executive leaders to engage in discussions about how they might be taught and learned within an organization or how, when, where, and why information flows—or might flow—within an organization. In turn, firefighters might develop innovative solutions to improve information flow or identify moments or opportunities when their situated knowledge could enrich decision making or risk assessment. For instance, rather than relying solely on an officer’s ability to read fire behavior and interpret risk, an early career firefighter might save fellow firefighters by identifying and communicating signs of an impending flashover.

Put differently, these visualizations owe much to previous research. They seek to build on Sauer's earlier studies of embodiment within the mining industry by illustrating that firefighters access and construct "embodied sensory knowledge" (Sauer, 2003, p. 182) by enacting literacies as practices in situated moments and places. Drawing from Clay Spinuzzi (2003a, 2003b), Laurie Gries (2015), and Liza Potts (2009), the network visualizations seek to account for relationships and information flows between human and non-human agents. Indeed, while they might be lurking in the background, the data visualizations found here demonstrate that written documents have a particularly powerful role on practice, as national standards and standard operating guidelines written by physicians, engineers, scientists, manufacturers, policy makers, and executive fire officers shape the work firefighters perform. Ultimately, when I look at these visualizations, the characteristic that stands out most prominently is that firefighters’ literacies are inflected by the hierarchical rank structure of the fire service. Class pervades work in even blue-collar occupations. Chief Burke leverages the incident command system (ICS) as a heuristic for managing firefighting operations. His account, and my visualization of his account, draws attention to the managerial role he occupies. His practices include visually observing crew work, aurally listening for signs that suggest a crew is in trouble, distributing assignments and giving orders to companies, taking notes on his yellow notepad to aid his memory, as well as developing (and continually assessing) an operational plan to ensure that incidents are mitigated efficiently and safely. In comparison, the visualization of the Orderville Special Hazards Company foregrounds the important ways that members work as a collective mobilizing touch, movement, sound, and other forms of perception to co-navigate a smoke-filled, zero-visibility environment. In sum, the visualizations presented in subsequent sections of this webtext matter because they could be leveraged as a powerful metacognitive tool for firefighters—across rank—to reflect on their work. They can illuminate tacit practices that are often unseen and non-discussed, which, in turn, enables newcomers to or outsiders from the profession to better understand and value the vast pools of intellect and knowledge that firefighters possess and make use of daily.