Beth Hewett started her book by discussing the value of online one-to-one teacher and tutor conferencing with students. She developed her discussion of online conferences describing the use of technology (e.g., email, internet access, computer access, etc.) as a connection point for the teacher-student interaction, but she cautioned the assumptions teachers make related to accessibility and equal access to technologies. For example, Hewett (2015) explained that some students may have limited or no access to the internet, use low bandwidth, or use older technologies, which would impact a student's “equal access to technology” (p. 14). Hewett indicated the importance of assessing a student's comfortability with technology because familiarity with social media does not necessarily equate to comfortability with using technology in a formal academic environment.

Hewett discussed the different types of conferencing, comparing synchronous (face-to-face) conferences with asynchronous text-based conferences, to establish the benefits and limitations of both practices. However, her primary focus was the asynchronous text-based conference, which emphasizes textual forms of communication rather than verbal exchanges between the writing teacher and the student. Asynchronous text-based conferences can take the shape of email exchanges and Instant Message chat (IM), which provides global (i.e., generalized comments) and local (i.e., specific comments on the students’ writing) feedback of the students’ writing. The author argued that one-to-one asynchronous conferencing allowed writing teachers and tutors to provide “both supportive and critical instructional commentary—as explicit tasks” (p. 18). It is important for instructors to guide students in the online learning environment, providing them with feedback that reinforces writing strategies and assistance when they are struggling with key concepts (Riggs & Linder, 2016, p. 3). The interactions between the writing teacher and the student are framed in a problem-solving schema, which can be narrowly focused to address specific student writing challenges or more broadly address overarching challenges that the student is facing in their writing.

Throughout the book, Hewett (2015) grounded the discussion of conferencing by providing transcripts of teacher-student and tutor-student conferences that illustrated how writing teachers or tutors interacted with a student, asking clarifying questions and providing focused global and local feedback to the student. The author encouraged a systematic problem-centered interaction with the student that encourages the student to critically examine their writing. Hewett described what worked and what could be improved upon in each teacher-student conference scenario, which reinforces a "best practice" approach for online writing conferencing. Furthermore, Hewett (2015) emphasized that the teacher and/or tutor “consider their students’ various abilities to take in the instruction aurally,” which is especially important if digital/video feedback is provided in the asynchronous response of the students’ writing (p. 35).

Since the online learning environment may be new for some students, it is important for teachers to provide clear instructions to their students, guiding them on expectations related to their individual conferences. The author argued that it is necessary for teachers to clarify expectations on how students should respond to teacher/tutor comments, provide digital examples to help reinforce writing expectations, clearly state what students “must do” and what they “might do” in relation to the feedback they receive in their conferences, and establish the students’ role in the conference to promote an active learning environment (pp. 59–60, 71). Other online instruction practitioners support this pedagogical practice. Scott Warnock (2009) stated that the interaction between teacher and student can establish expectations in the online learning environment (p. 123). Continuing the approach of best practices in online writing conferencing, the author stated the significance of “writ[ing] explicit and linguistically direct comments” because it will reduce the students’ likelihood of misinterpretation or confusion during the conference (p. 82). Furthermore, the author indicated the necessity for teachers and/or tutors to use vocabulary that is concise, direct, and appropriate for the student to comprehend, which highlights some of the challenges online instructors face with asynchronous text-based communication.

As Hewett expanded on best practices for teachers and/or tutors conferencing in online writing courses, she acknowledged that the individual initiating the conference will be more active in the conference commentary because of their active interest in the purpose/outcome for the conference (p. 132). However, Hewett (2015) quickly indicated ways in which the teacher and/or tutor can encourage a students’ interest in the conference, such as:

using the students’ names and speak directly to them, encouraging them to speak directly to us; use context cues (references to the students' writing); ask students open-ended questions; ask students if they have their own questions; require students to commit to their ideas to writing; check in frequently regarding students’ understanding of what is being said; offer clear, honest, critical responses to the writing; and finally, be personable. (pp. 133–134).

As a final guide for novice teachers and tutors, Hewett (2015) emphasized ways to audit student learning and teaching practices that includes the value of “instructional rubrics, interactive journals, spontaneous or scheduled chats, midterm and end-term surveys, and self-audits” (p. 155). The author articulated the value of rubrics because they provide students with feedback that illustrates clear expectations for the written assignment; but rubrics also help students and teachers gauge writing progression on draft versions of an assignment. Additionally, task-specific rubrics can provide helpful informal feedback for students about their writing (Bean, 2011, p. 280; Selfe, 2007, p. 19). The overall foundation of the author’s argument concluded with reiterating the value of conferencing for online students, and its ability to help students grow as writers.

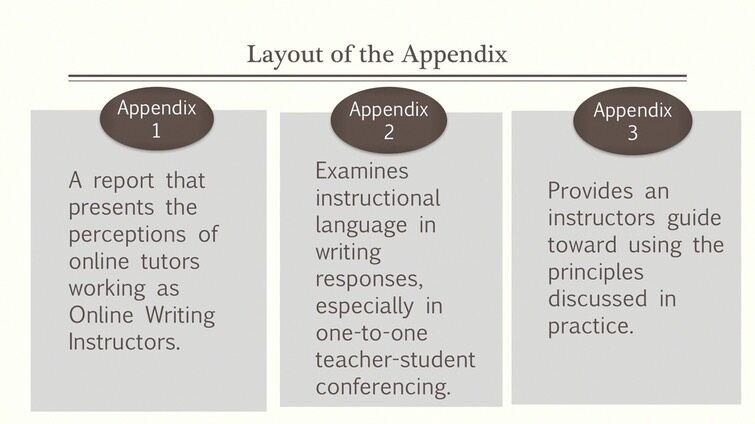

Appendix Section

The first appendix included a scholarly report by Christa Powers, titled “A Study of Online Writing Instructor Perceptions,” which provided some additional background information on the theoretical approaches of online tutoring. The report presented aspects of tutor experiences with asynchronous and synchronous instruction, providing a methodological context for conferencing. Commonalities between the report and Hewett’s book included the examination of pedagogical challenges of online conferencing for instructors and tutors, attitudes of online writing instruction, and the benefits of one-to-one conferencing.

The second appendix contained information on direct and indirect speech use in writing responses from instructors and tutors to students. This section presented areas for further research, such as instructional language and feedback used in the student review process. It also included some teachable moments in student conferencing interactions that can be both positive and rewarding for the student. Hewett provided a rhetorical approach for conferences, outlining how instructors and/or tutors can avoid the hazards of miscommunication, which can occur in text-based conferencing. Similar guidelines for making one-to-one conferencing successful and efficient were noted by John Bean (2011) in which he stated, “conferences should focus primarily on helping students create good, idea-rich arguments and wrestle them into a structure that works” (pp. 304–305).

The third appendix included an instructor’s study guide with lessons and problem-solving approaches for each chapter. Hewett constructed the pedagogical framework of her book into a “best practices approach,” helping circumnavigate some of the technical and communication issues that may arise for a new online writing instructor. She also included potential scenarios that an instructor may experience with a student, offering helpful suggestions to make the conference and lesson process more successful.