Beyond tackling the heady and often theoretical scope of austerity writ large, Nancy Welch and Tony Scott have also included finer-grained looks at programs and the effects that outcomes and austerity have had on them. These offer more nuanced and detailed support for larger claims about neoliberalism and austerity made by others in the volume. Emily Isaacs, in "First-Year Composition Course Redesigns: Pedagogical Innovation or Solution to the 'Cost Disease'?", reviewed data on course redesigns from the non-profit National Center for Academic Transformation (NCAT). While NCAT appears promising to help contain costs relative to more homogenous technological solutions like MOOCs through what it calls Course Redesign, Isaacs ultimately faulted much of it for "push assessing (think: push polling): a reinvigorated focus on grammar and other lower-order concerns, and a procedural, lowest common denominator interpretation of writing as a process" (p. 52). Similarly, Marcelle Haddix and Brandi Williams, in "Who's Coming to the Composition Classroom? K–12 Writing in and outside the Context of Common Core State Standards," examined Common Core State Standards (CCSS), not for what they specifically do, but for what they leave out. As Haddix and Williams claimed,

The problem is not the emphasis on these three writing styles [argumentative, informative, and narrative as the focus of CCSS], but the de-emphasis on other writing styles that may allow for a more creative expression that youths experience through digital and other media outside of school spaces. (p. 65)

They contrasted CCSS with Writing Our Lives, a writing project for urban youth that "creates a space for youth writers to come out and be known as writers" (p. 66) and noted that, under CCSS alone, "there may be limited opportunities to engage in extended writing projects in multiple genres and for diverse purposes within the school context" (p. 72).

Part Two: Composition in an Austere World tackles many of the known areas and institutions within the field of composition: the National Writing Project (NWP), basic writing, prison literacy programs, public rhetoric, and First-Year Composition (FYC). Tom Fox and Elyse Eidman-Aadahl detailed the effects of removing directed federal funds to the organization in "The National Writing Project in the Age of Austerity." They noted how NWP, as a non-profit institution, is pulled in several directions as different funding interests shape the work it can do. They provided a short history of the NWP both during and after federal funding, which I am sure will be of value to historians of the field. They noted the current prominence of randomized control trials (RCTs) "as the 'gold standard' for educational research" (p. 87) that can be scaled and compared across contexts according to the What Works national database. In the end, they suggested an intriguing détournement of systems by local agents in a long line of theorists from Pierre Bourdieu to Henry Giroux, from Gerald Vizenor to Galloway and Thacker. As they stated, "Working in the age of austerity is more work" (p. 89), and that work is always rhetorical, as risky and unfair as it might sometimes be.

In "Occupy Basic Writing: Pedagogy in the Wake of Austerity," Susan Naomi Bernstein juxtaposed Occupy Wall Street and basic writing, "one of austerity's first victims" (p. 92), at CUNY in the wake of the 2009 elimination of open admissions at the community colleges. Her contribution is relentlessly personal, reflecting at times on the death of a friend, her job loss, her dissatisfaction with protests, and her move to Arizona. In this way, and explicitly conscious of educational scholarship by Mina Shaughnessy, Ira Shor, Paulo Freire, Amy Winans, and Jacqueline Jones Royster and Gesa Kirsch, Bernstein weaved a tapestry that called for "a revised epistemology; ways and means of knowing based on material realities and embodied events of everyday life in the wake of austerity" (p. 104).

Taking up the remaining "tatters" of prison education in "Austerity behind Bars: The 'Cost' of Prison College Programs," Tobi Jacobi questioned the true costs of austerity on the prison system from the perspective of composition as "part of the core curriculum in these prison college programs" (p. 107). Jacobi drew from critical intellectuals like Angela Davis and Jimmy Santiago Baca and from think tanks like the RAND Corporation and Pew Center on the States to ask seemingly small scale—but critically important—tactical questions: "At what point do we ask this system to engage issues of justice beyond our own labor and on-campus students' needs? Where and when will we advocate and for whom?" (p. 116). Her attention to tactics in a book largely about broader strategies (be they conscious or not) is a welcome one, figuring as many of these more local contributions do into the contingent and sometimes idiosyncratic nature of composition work.

Administrative bloat and the rise of "deanlets" occupy much of Eileen Schell's contribution, "Austerity, Contingency, and Administrative Bloat: Writing Programs and Universities in an Age of Feast and Famine," while Ann Larson's chapter, "Composition’s Dead," focused on the role of contingent and contract labor in composition's austerity. Here again lies a tension between and across the volume's contributions, a tension often between larger questions of strategy and local questions of tactics. Schell stated that her

goal is not to denigrate admnistrative positions or those who seek them, but to ask tough questions about how money spent on managing the university organization and university programs and funds allocated to 'entrepenurial' or extracurricular initiaives have to be balanced against monies spent on the instructional budget in the form of stable, well-paid positions. (p. 178)

Larson was more strident and grounded in a traditional Marxist view, in which "'the people who actually teach writing,' to use Harris's phrasing" are the real heroes operating in a world of alienated "zombie" labor (pp. 172–173). Larson advocated "that we examine and discredit ruling class rhetorical tactics that erode solidarity" (p. 174), again pointing, as so many contributors did, to tactical maneuvers grounded in our repsective places. For her part, Schell pointed to what I think is really at stake here: "we are in a battle for the soul of shared governance" (p. 185). Divisions between academic contract labor, tenured or tenure-eligible faculty, administrators, and student services staff are exploited for many reasons, few of which allow for robust, democratic conversations. Schell described one tactical approach "to take steps to address these issues on our own local campuses" (p. 185) in the form of Syracuse University's Campus Equity Week programs sponsored annually by the Labor Studies Working Group.

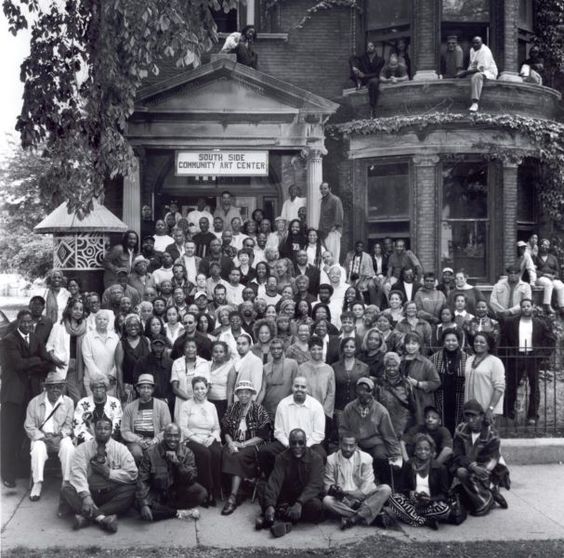

Mary Ann Cain's essay, "BuskerFest: The Struggle for Space in Public Rhetorical Education," detailed a public literacy progam in Chicago's Bronzeville Art Center, and she used a different narrative tone to drive its argument. While she detailed the unhoming of Three Rivers Institute of Afrikan Art and Culture, a public afro-centric literacy program, Cain announced that her purpose was "to provide here-and-now observtion of micro-moments of public space-making in and beyond writing classrooms as a way to understand how public space is made by claiming it" (p. 121). In the end, Cain was "hopeful" because she and her students "are all now connected in ways we never could have imagined on our own. And we can tell others about why they should want to be, too" (p. 130). Through such attention to public space and the rhetorical effects of repetition, Cain crafted a bright narrative in an otherwise dark book.

Continue to Statement.