Interruptions in Relatedness:

Reflect on the affective disruptions we experience

As noted throughout this webtext, Yik Yak was often a controversial presence on college campuses, given the possibility for the platform to be used to target specific groups or individual members of campus communities. Students in this sample communicated a range of attitudes towards the application, some seeing it as "harmless fun" (Phil), others identifying its problems and placing it "in limbo" (Robert), and several describing it as harmful ("I do not think I will continue to be a part of it because I do not believe it has many positive effects," wrote Claire). These characterizations of the application suggest that content on the application was often emotionally charged, resulting in high levels of "affective intensities" (to use Susanna Paasonen’s term to describe what drives online exchanges and our attachments to different platforms, threads and groups). In Yik Yak’s case, the interactions within the network were dynamic because of these intensities: "attention shifts and clusters within the network while intensities grow and fade" (Paasonen, 2010, p. 31). However, affect is an experience of feeling that lasts long beyond the moment of emotional encounter, creating linkages between us and ideas, events, things, and even other people. Affect can be described as the level of "towardness" or "awayness" one feels in regards to an encounter (Ahmed, 2014, p. 8), and these levels vary, according to the factors discussed in this webtext.

If we utilize an ecological framework to examine the shifting nature of Yik Yak networks, we accept the process-driven, fluid nature of the platform and its rhythmic flows. Such an approach also allows us to see the intensities with which different affective processes are circulating, and perhaps more importantly, the disruptions within these processes. As affect is based on relations between us and an object, an interruption in a relationship dissuades us from moving closer to it. As Gregory Seigworth and Melissa Gregg (2010) noted, affect determines whether a body belongs or doesn’t belong, based on the intensity with which that body reacts to an idea, object, or experience (p. 2). Different feelings conjure up different affective orientations; certain sensations, such as fear, hatred, and disgust are noted especially for their propensity to interrupt relations. The problematic posts that many students referenced in their reflections can certainly be described in terms of affectual interruptions, ultimately illustrating the complicated nature of this network and its capacity to foster feelings of belonging and not-belonging among its users.

Some interruptions are clearly marked by the intense emotions noted above, while others can be surmised through a lack of communication or exchange. The presence of extreme feeling provides an easier path to trace than silence or a refusal to engage, but gaps in communication are incredibly important for us, and our students, to notice on these platforms as well. By exploring the affective intensities behind these interruptions, students can ideally become attuned to these patterns so that they may perhaps intervene in order to reverse these interruptions, working towards higher levels of relatedness. While the anonymous, place-based nature of Yik Yak allows us to see these patterns perhaps more clearly, an awareness developed via these types of applications can potentially be useful when viewing exchanges on profile-based social media platforms, which foster connections as well (though admittedly through different means).

Fostering (not) Belonging through Interruptions

In my own experiences on the application, I noticed an unsettling amount of open hostility towards minority groups, including international students. At Purdue, where this group makes up 23% of the total student population (Purdue International Students and Scholars Office), one can imagine the frequency of posts like those featured on the Yik Yak page. One student in this study had spoken with me several times throughout the fall semester about his frustration with the level of discrimination towards Asian international students he had witnessed on our campus. In his response to the assignment, he directly tackled this topic. In an insightful conclusion, Adam wrote:

It’s hard for me to be able to justify the things being said on Yik Yak when one hasn’t been in the other’s shoes. The transition for international students is a tremendous one that domestic students seem to overlook. The students are thousands of miles away from home and anyone they know. Being culturally sensitive is not one of Purdue’s strengths. If the Yak community could understand what some of the students have to go through on a daily basis the posts might be different. A much-needed feature on Yik Yak is a sympathy feature.

Adam’s intense feelings towards the platform’s propensity for hateful posts show through in this reflection. (As Adam is the child of Japanese immigrants, it makes sense why he would be especially bothered by these types of posts on the application.) I am intrigued by his idea of a sympathy feature to place users "in the other’s shoes," especially in light of the importance of connection when it comes to the experience of positive affect. Perhaps such a feature would lessen the frequency or even the potency of hatred, which produces a "differentiation between ‘us’ and ‘them,’ whereby the ‘they’ are constituted as the cause of ‘our’ feeling of hate" (Ahmed, 2014, p. 48). This differentiation creates an interruption between parties, lessening the possibility of identification and subsequent movement closer to each other. The posts that Adam responded to in his reflection represent the original poster’s "negative attachment to an other…that is sustained through the expulsion of the other from bodily and social proximity" (Ahmed, 2014, p. 55). By citing commonly-accepted stereotypes and emphasizing cultural differences, these posts create an insurmountable distance experienced by both parties. Such a distance can ripple into the physical world, and subsequently show up again in digital spaces, enforcing a cycle of these affective interruptions.

Despite his thoughtful critique noted above, Adam actually emulated the same behaviors that he found so offensive in other users. Assumedly in an attempt to see if other groups were subject to the same treatment, he decided to post about African American students. He wrote, "I got a negative response from the yak community when I referenced the black community. It was interesting to find that the yak community is sensitive to humor toward African Americans. I then turned my attention to the Asian community…The yak community seems to favor racism toward the Asian community." I was alarmed when I read this, and also confused that he would take part in the same kind of posting practices that he had found offensive.

It is possible that Adam, feeling alienated by the negative posts about Asian international students, tried to lessen the intensity of this sensation by trying to foster a similar dynamic between the majority of the student body and another minority group—thereby positioning him closer to the norm. This was perhaps the result of fear, as it "re-establishes distance between bodies" and "involves relationships of proximity, which are crucial to establishing the ‘apartness’ of white bodies. Such proximity involves the repetition of stereotypes" (Ahmed, 2014, p. 63). Hatred and fear go hand-in-hand, especially in the effects that they have on excluding bodies as they disrupt linkages in networks like this one. It is also possible that Adam could have just been experimenting, as the assignment asked him to do ("Please experiment—try different rhetorical moves, different patterns and styles of speech, and see what works best—what gets the most upvotes, what disappears, and so on."), without considering the harmful behaviors he was falling into.

(I want to note here that this reflection has haunted me ever since I read it for the first time. If we do incorporate anonymous, location-based social media applications into our writing classrooms, given their complicating factors, we need to position our students to do this work ethically and carefully—something that I feel I failed to do in this situation. See the "Anonymity" page for more on this.)

Trying to Bridge Interruptions to Restore Relatedness

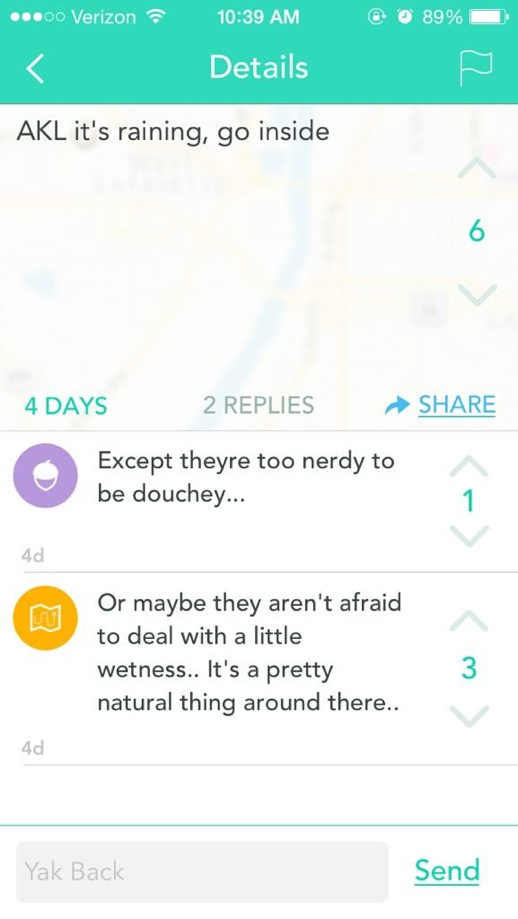

Adam's scenario points to the complexities of anonymous applications: anonymity provides the opportunity to operate in networks without being personally identified by other users, but it’s incredibly difficult to shed one’s physical, bodily identity. For some users, that represents further alienation from dominant groups; for others, their real-life status perhaps empowers them to facilitate disruption instead of only experiencing the fallout of disruption. One student in this sample, Brian, discussed his own experience with his fraternity being targeted several times on the application during the duration of this assignment. The screenshot (at right) shows the post that Brian reacted to due to its disparaging attitude towards his fraternity.

He responded directly to one such post, directly addressing the original poster in the second comment above ("Or maybe they aren’t afraid…). Reflecting on his approach, he wrote: "I don’t enjoy these posts when others go out of their way to try and bash or talk badly about something…I obviously wanted to add some humor in the post and maybe even a little suggestive innuendo, but I wanted to try and do it in a positive…way." The intensity of the original post was far less potent than others that can be found on the application, and Brian’s response was equally tempered, perhaps even lighthearted. I would also surmise that, Brian, as a white male, felt empowered enough in his physical identity to respond directly to the post, while members of marginalized groups like international students or racial minorities may not feel they can be taken seriously on the application if they respond directly in a way that reveals their bodily identity. Or, if they do respond, they fear that their responses may be down-voted quickly and disappear from the feed, leaving them with very little recourse to these original posts. This scenario represents the possibility for "qualitative affordances" (Tarsa, 2015) like replies and down votes, to silence particular groups, given the way that Yik Yak was designed.

Not Responding to Posts: Interruptions?

Despite the fact that many students commented on the presence of racist, sexist, homophobic, xenophobic, and other problematic posts on the application’s feed in their reflections, no student in this sample wrote about intervening in these conversations. (They very well might have done so, but they didn’t reveal that to me via their screenshots or reflections.) Instead, I assume that when they (and, I dare to say, most users) encountered these posts, they ignored them and chose not to engage with them. This act, while seemingly passive, is caught up in power relations:

Power speaks here in this moment…Do you go along with it? What does it mean not to go along with it? To create awkwardness is to be read as being awkward. Maintaining public comfort requires that certain bodies ‘go along with it,’ to agree to where you are placed. To refuse to be placed would mean to be seen as trouble, as causing discomfort for others. (Ahmed, 2010, p. 39)

On Yik Yak, and other social media platforms, "going along" with something could describe several different behaviors, of varying degrees: a user could merely scroll past the post; they could read it and smirk (or frown); they could upvote it, they could even go so far as to leave a comment on the post. Though the level of commitment varies (along with the accompanying affective intensity implied by that particular commitment), the end result is that these bodies appear, to the network, to be complicit in that sensation. By maintaining their silence, users avoid creating awkwardness by not interrupting the rhythms of discourse established by the original post. Though they might actually find these posts incredibly distasteful, their silence may imply otherwise. If we don’t experience positive sensations by feeling close to objects that are viewed as good by others in our "affective community," we become "affect aliens" who don’t experience the accepted or expected emotions designated by the larger group. As if this alone wouldn’t make a user feel out of sorts, to interrupt the rhythm would be to step into the role of a kill-joy, actively disrupting the closeness of others (Ahmed, 2010, p. 37).

So, silence in response to such posts has a variety of potential meanings: the lack of engagement seen across platforms where these types of exchanges take place is, in fact, ambiguous, and brings up questions about the relationship between silence and non-response in digital spaces. More exploration on silence in digital spaces, especially on anonymous and location-based platforms designed for discussion, is needed as we continue to engage (and sometimes, disengage) via these applications.

While many forms of social media do have the capacity to build community among users, anonymous applications that use geographic location instead of personal profiles and relationships to structure networks present users with a kind of pseudo-community: users experienced affective intensities through their exchanges on the application, and feelings of belonging (or non-belonging, perhaps) flooded over them, but the network was so unstable that nothing lasting could be built. As Jodi Dean (2010) argued, "Affective networks produce feelings of community, or what we might call ‘community without community.’ They enable mediated relationships that take a variety of changing, uncertain, and interconnected forms as they feed back upon each other in ways we can never fully account for or predict" (p. 91). The constant disruptions and interruptions that bombarded users of Yik Yak were the result of the temporal and technological qualities of the application. This pattern, perhaps present on other platforms, prevents true communities from forming, instead providing fleeting moments of communion, or alternately, alienation. Identifying these moments of interruption allows us to see how other factors bring these situations into being, and we should reflect on these moments so that we can help students to navigate them in the future.