Rhetoric Revealed (Ch. 1–5)

This first third of the collection implicitly interrogated a critical-rational approach to rhetoric in public life by looking at what happens down on the ground when rhetoric and power tangle.

Ch 1 - Should We Name the Tools?, Carolyn R. Miller

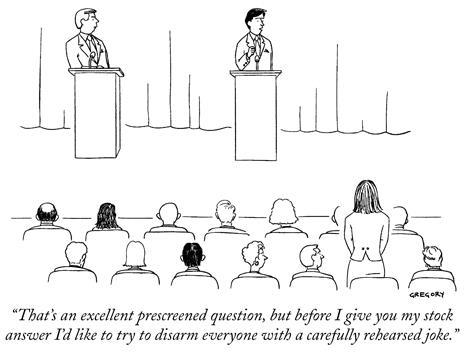

Figure 2. The New Yorker Collection (Gregory, 2000)

Carolyn Miller laid out a serious conundrum for rhetors and rhetoricians: Rhetors who would be perceived as trustworthy must hide the tools and

hide the hiding of the tools (p. 28). Rhetoricians who would teach rhetoric must reveal and elaborate the tools of rhetoric (p. 29). More

perplexing, for readers of this book is what this means for the public work of rhetoric: If rhetoric can be more effective, more useful,

more powerful, if it remains concealed, what can it mean for rhetoric to go public? What can its ‘public work’ be?

(p. 21). Most of the

chapter is spent systematically teasing out the justifications and consequences of concealment. Miller argued that an adversarial model of

human relations and a mimetic model of language create the need for hiding rhetorical tools. When language is understood to be mimetic—when

words correspond directly with things, acting as a mirror of the true nature of objects—then spontaneity and sincerity serve to counteract

suspicion. When we prepare (or seem to prepare) our words, we might (appear to) be hiding or skewing or (mis)shaping the true nature of things.

Miller claimed we can understand the denial of rhetoric, its need for concealment, as the consequence of these two enduring

conditions and their interaction

(p. 29).

Miller pointed to rhetoric’s long history of drawing on combative, acquisitive, or acquiring arts—boxing, wrestling, hunting, and military

strategy—as illuminating points of comparison. Further, she called on Herzog (2006) to note that the problem isn’t simply that some people are

dishonest rogues

and that we cannot reliably determine who the dishonest rogues are but that a social situation where material resources,

power, or knowledge are unevenly distributed may cast reasonable, mostly trustworthy people as adversaries (as cited in Miller, p. 29). It is under these conditions

that Miller then asked at the end of the chapter What can rhetoric’s public role be under these conditions? What can its educational project

be?

(p. 30). Miller offered no easy answers here, and instead pointed briefly to possibilities that scholars like Wayne Booth (2004) have

commended—the public work of rhetoric might be to instantiate a cooperative rhetoric—even as they note their own difficulties with enacting those

possibilities. Miller closed with a two-fold disclaimer: 1) she is not ultimately aiming to dismiss rhetoric as a sham art but to reveal the

powers and dangers of rhetoric and 2) that whatever way forward we choose must be tested with a case-by-case realistic attention to and risky

venturing of our hopes for what it is that rhetoric can achieve in public life (p. 33). I take time to elaborate Miller’s argument here because

the problem she names is relevant to many of the chapters in this collection and raises hugely important questions for the work of rhetoric and

the rhetoric of rhetoric.

At the end of the chapter, Miller seemed to be answering the question of the chapter’s title—Should we name the tools?—with Yes, in the

classroom

and No, in the street.

And here, I find myself wondering about the conditions under which we might elaborate tools both in the

classroom and in the street. Consider the self-other relations and the work of language: what would it mean to name tools to shift the very terms

of engagement and to re-cast the (perception of the) work of language not as (only) mimetic and combative but instead as (also) inventive and

dialogical? If we are not trying to conceal social relations and their accompanying power dynamics and interests but instead trying to lay them

bare, and, if we are trying not only to combat and persuade but also to listen, deliberate, and invent, then might there be something useful in

naming the tools? Might we name the tools in a way that constructs (rather than simply protects) our ethos as trustworthy? While some chapters

in this collection, including Candice Rai’s and Ralph Cintron’s, have made the difficulty of

this project clear, others, including Linda Flower’s and

Jeff Grabill’s, illustrated the possibilities when naming the tools is central to the public work of rhetoric.

Ch. 2 - Power, Publics, and the Rhetorical Uses of Democracy, Candice Rai

Ch. 5 - Democracy and Its Limitations, Ralph Cintron

Candice Rai’s chapter, which focused on the contradictory deployment of democratic rhetorics, works in tandem with Ralph Cintron's chapter, which focused on the limitations of democratic topoi as storehouses of energy (Cintron, p. 100). Cintron’s chapter, along with Rai’s, might be seen simultaneously as deep critiques of the limitations of democracy and the ambitions of rhetoric (Cintron, p. 99). Taken together, Rai and Cintron illustrated and theorized democracy as topos—a motivating action—that energizes by way of its virtue. Where Rai showed the ways everyday citizens sought to leverage an assumed, shared virtue of democracy, Cintron theorized and called into question the ontologization of democracy as somehow virtuous. He claimed that key terms of democracy function as topos which manufacture sufficient energy to organize perspectives and actions of very large communities. Rai showed, in the context of a debate about the future of an urban neighborhood, that two topos—democracy as an inclusive democratic process and democracy as justice—produced motivation and organized the actions of individuals and groups with diametrically opposed agendas. Rai illuminated how this played out in a gentrifying neighborhood outside of Chicago where stakeholders were trying to determine what to do with a plot of land known as the Wilson Yard.

The resources related to Wilson Yard reference, and hopefully humanize, some of the historical contestations and coalitions of community organizations Rai analyzed in her chapter. They especially foreground the appearance and reality of democratic deliberation, including the difficulties of inclusion when dialogues are drawn out over ten years. The linked article about Chicago Uptown’s alderman Helen Shiller discussed her legacy in the wake of the collective planning processes to design. The Chicago Rehab Network’s site revealed a coalition of organizations committed to serving Uptown, who were not only down and out but often the target of gentrifying rhetorics in the Wilson Yard discussions. Finally, the linked video offered news coverage (2007) of a critical juncture in the discussions of Wilson Yard that took place in the thick of fieldwork Rai conducted between 2005 and 2008.

Resources Related to Wilson Yard Fire

Figure 3. Wilson Yard fire 10-year anniversary (uncchicago, 2007)

Cintron, on the other hand, noticed that rhetorical scholars also leverage topoi to cast their own work as having an automatic virtue,

as if inclusion were somehow inherently virtuous. Cintron not only contended that inclusion is not in and of itself virtuous but also that

it is not pragmatic, something Rai’s chapter made clear. Certainly, material limitations shrink the good intention to include

(Cintron, p. 103), but he also raised the point, through a local alderman, that inclusion might also sometimes shrink justice. Considering these

tensions, Cintron, who situated much of his work in this chapter amidst his latest fieldwork in Kosova, asked and answered: Why does the demos

as deep artifact never arrive?

(p. 106). He argued that democratic topoi call on and manufacture desire; power has an incessant need to manage that

desire. These two forces are as incompatible as they are insatiable. Power then works to protect its accumulated advantages and capital while

managing desire that threatens those advantages through the construction of laws which manage exclusion and inclusion.

Toward the end of their respective chapters, both Rai and Cintron returned to the pragmatic: Rai argued that democratic mythos obscures the

more important question of whether various social investments do or do not produce desirable and just social consequences. However, it is

precisely the content of desirable and just action that democratic rhetorics cannot finally determine

(p. 51). Cintron asked, How do

we determine the public good? How might we improve the public sphere?

(p. 111). Neither seemed to imagine a way forward for a productive

rhetoric in an actionable democratic enterprise. Cintron seemed to question the capacity of rhetoric for operationalizing productive public

deliberation, and he offered a Kantian dismissal of those who would call for improvements to the public sphere, as if their own self-interest

somehow negated or contaminated a simultaneous interest in improving the public sphere — as if the two need to be separate somehow.

Interestingly, the critiques Rai and Cintron raised mark points of departure both from the pieces in this collection as well as for some of

the most important work in postmodern phronesis. For example, these chapters notably deviated from the work of Bent Flyvbjerg (2001) who both

looked at actually existing democracy in city planning and theorized a well-tooled extension of Aristotelian phronesis that takes up questions

of power as a central deliberative practice for determining public good and improving the public sphere.

Ch. 3 - The Public Work of Critical Political Communication, M. Lane Bruner

M. Lane Bruner argued that [t]he public work of rhetoric is to critique the distance between our ideational and material economies as best

we can

(p. 59), and he forwarded methods for approaching what he called critical political communication to do this work. Critical

political communication, according to Bruner, is an ongoing investigation into the relationships among disciplinary discourses, identity

construction, and the healthy state

(p. 57).

Resources Related to Rejected Public Discourses

Figure 4. President Bush Addressing Congress After 9/11 (The9112001, 2012)

He connected this work to the public work of rhetoric:

Healthy publics and, therefore, healthy states institutionally guarantee thick public spheres, and in doing so they maximally anticipate the indirect consequences of conjoint action by encouraging the proliferation ofcounterpublicswith sufficient force to ensure constant critique of laws, institutions, and disciplinary measures. Sick publics and therefore sick states conversely suppress critical thought in a wide variety of ways… (p. 61)

The importance of this work, therefore, is in the possibility of better understand[ing] the relationship between discourse and the

political

in order to leverage available means to productively transform sick publics and states into healthy publics and states

(p. 61).

To do this, Bruner engaged in limit work

looking at dramatically rejected public discourses because they reveal the limits of hegemonic

discourse. He articulated a critical-material-genealogical approach to rhetorical criticism, carefully putting poststructuralists in conversation

with pragmatists. (Readers won’t want to miss Bruner’s footnotes teasing out important theoretical distinctions; in fact, the footnotes alone make

this chapter worth reading!) Examining the distance between what people think is true and what is actually true, and the terrible consequences of

that distance, Bruner then turned to three illuminating examples: 1) the experiences of Paul Baumer in Erich Remarque’s (1929) All Quiet on the

Western Front, a fictional account of a German soldier’s experience of the First World War; 2) discourse about the attacks against the United

States on September 11, 2001; and 3) two speeches revealing the ways the Holocaust is remembered in East and West Germany. Toward the end of the

piece, Bruner argued that one way to do the public work of rhetoric is by mapping the distance between history and memory, understanding how

far those imaginaries are from historical fact, and with what consequence.

The resources above offer links to trailers of three films Bruner referenced in his chapter. I have included the trailers in hopes that

they might ground discussions of the limit work that Bruner conducted by illuminating how relevant instantiations of healthy and sick publics are

to our own everyday cultural experiences, symbols, and narratives. In particular, these films might offer insight into the ways we sometimes map

or gloss over the unspeakable, whether the unspeakable includes the atrocities of war or the sense that we are living in a staged world,

deliberately sheltered from realities that might stir us to be and do and relate differently. Additionally, the link to former President George W.

Bush’s speech after 9-11 also offers a historical snapshot that raises questions about the deep distance between what most people imagined

was true and what was actually true

(p. 63).

Ch. 4 - Rhetorical Engagement in the Cultural Economies of Cities, John M. Ackerman

John Ackerman analyzed the ways civic engagement,

on the surface a term that aligns with rhetoric’s interest in the polis, is

implicated in global economic policies. As civic engagement has become a trope equal with innovation, entrepreneurialism, and global economic

competitiveness

(p. 77), it has become less associated with classroom learning or experiential learning ventures and more with the realm of

economic, educational, and geopolitical policy. These policy spheres are tangled with globalized fast capitalism, neoliberalism, neocolonialism,

and neo-imperialism. Ackerman argued that when the logics and mechanisms of globalized capitalism subsume other logics in the realm of civic

engagement and progressive education, the public work of rhetoric involves unraveling the discourse and its material consequences. In his analysis,

Ackerman noted the ways universities have leveraged civic engagement

to fashion themselves after the latest demands of a globalized market

hungry for values-laden products and free or replaceable labor. As universities have sought to distinguish themselves in a hyper-competitive

market, they have offered more opportunities for internships, service-learning, and work experiences that may pad students' résumés

while providing the university and its corporate partners free labor. While the university gets to brand itself as a change-maker,

students

pay for the privilege of laboring, and corporations continue to make bank on the backs of contingent, replaceable workers.

Ackerman then charted connections between a revitalized democracy and a new economy

derived from Clinton-era politics that harnesses

civic life to transnational economies and free-market expansion

rather than to nationalistic or class-based notions of citizenship (p. 80). In

this model, the polis is transnational and a citizen’s participation and contribution is primarily economic. And yet, in this model a

free-market economy is deemed too important to be tampered with, making the aims of civic engagement de-regulation of the economic realm and

making the means of civic engagement labor and consumption. Among many disturbing implications, one is that citizens can labor or they can

participate in social institutions like family or church, but they should not, at least under this model, speak back to public institutions or

to corporations that might somehow shape or regulate economic policy and practice. It is at this point that Ackerman introduced a question that

opens an avenue for situating rhetoric front-and-center in policy studies and cultural economies: [W]here and how does the citizen-scholar,

through individual and collective action, enter into those policy spheres that influence the political and economic consequences of civic life?

(p. 81). Ackerman’s question paved the way for his main claim that rhetoric must reclaim its status and usefulness in public life by producing

its own policy turn,

locating its public work in the middling range between everyday life in our communities and the regional economic

policies that influence them

(p. 81). Ultimately, Ackerman called for a reframing of rhetorical engagement from a service model to a model that

takes up economic processes and political struggles. Because our communities are never removed from global economics and because the global

economy is enacted through material and discursive elements that have consequences in our communities, rhetorical engagement must concern itself

with the cultural economies of our communities. Importantly, and in line with other rhetorical scholars considering the impacts of globalization

on the public work of rhetoric and writing (e.g. Payne & Desser, 2012; Dingo, 2012; Long, 2008), Ackerman contended that we can no longer pretend

that rhetorical agency exists outside the demands of capitalist command

(p. 81).

Ackerman ended the chapter by situating his own work in a middling range

of multiple economies in Kent, Ohio (p. 84). Ackerman narrated

collaborative efforts to navigate multiple models of engagement ranging from reflecting on visitor’s experiences of Kent State’s

historic past, to consideration of the town’s economic plight, to analyzing the town’s cycles of urban planning in order to make sense

of the construction of the cultural and economic memory of Kent, Ohio. Outside developers, city officials, local business owners, residents of the

city, and university officials worked together to re-imagine the cultural economy of the town through the design of the city. In participating in

deliberations over the town’s cultural symbols and economic needs, Ackerman’s work of rhetorical engagement sought first, to

understand how actually occurring cultural economies work and second, to engage in transforming the symbolic into the material (p. 90). It is in

this public work that rhetoric can shape creative economies

that have the potential to alter the policy spheres of local communities

(p. 90). The real value of this chapter lies in its three-pronged approach which sought 1) to re-position community partnerships and the public

work of rhetoric squarely in the global economy; 2) to rival service models and offer an alternative model of community literacy; and 3) to make

productive knowledge-building central to the work of creating infrastructure for civic engagement.

For readers interested in scholarship that takes up alternative models, arenas, self-other relations, and work for community literacy

initiatives, this chapter pairs well with Jeff Grabill's, with Linda Flower's,

and with Ellen Cushman and Erik Green's chapters. It also tracks with Elenore Long, Jennifer Clifton, Andrea Alden, and Judy Holiday’s chapter

Fostering Inclusive Dialogue in Emergent Community-University Partnerships: Setting the Stage for Intercultural Inquiry

in Barbara Couture and Patti Wojahn’s forthcoming collection Crossing Borders/Drawing Boundaries: The Rhetoric of Lines Across America.