Survey Methods and Results: Why Social Media Still Matters

Methods

The aims of this particular study are to provide a snapshot of social media usage within a specific context and to ascertain how this usage might demonstrate awareness of rhetorical practices amongst first-year composition students. As such, this assessment cannot be viewed as comprehensive and exists instead as a study of social media practices at a mid-sized Midwestern public university. It is limited both by this geographical location, and the fact that the opinions of the relatively small sample of represented individuals cannot be seen as emblematic of the entire population of first-year writers. This study primarily followed John W. Creswell's (2009) suggestions for research design, and it utilized two main methods of garnering data: an anonymous online survey and face-to-face semi-structured interviews with students. The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the university at which this study was conducted approved all materials associated with recruitment procedures and data collection. All images used in the survey (shown below) were obtained and modified from publicly-accessible profiles.

The survey, which was hosted on the Qualtrics online surveying platform, was distributed to all first-year composition teachers at the university via the departmental email list in Spring 2013. It was the decision of individual professors whether to forward the link to the Qualtrics survey to their classes. As such, seventy-four students participated in the survey, with the vast majority (89%) coming from the second r esearch-based course in the first-year writing sequence[1].Survey respondents wishing to participate in a follow-up interview were invited to indicate their email addresses; of the seventy-four survey participants, ten indicated their willingness to be interviewed, and when contacted, six were actually interviewed. These interviews were semi-structured and were recorded and transcribed. I view these interviews as the more critical aspect of this study because this medium provided students with the opportunity to freely describe their individual social media practices, something that typically cannot be achieved as comprehensively within a survey-based medium.

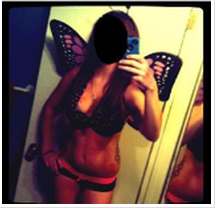

I designed the survey to first ascertain what social media sites students use and, of these sites, which one they engage with most frequently. The second aim of the survey was to determine how students perceive audience through both verbal and visual markers. Jane Mathison Fife's (2010) praxis-based activity, "Using Facebook to Teach Rhetorical Analysis," partially guided the development of these questions. For instance, she described how her students conceptualized the "partying motif," specifically "profiles that go beyond [the] display of a few casual party pictures" that can depict the writer as "a person obsessed with partying or a person trying desperately to seem cool by looking the part of the partier. Instead of just a few party pictures in an album, these cases might include a profile picture of the writer holding a drink along with many other photos of carousing" (Fife, 2010, p. 559). Thus, I was particularly interested in determining whether the students within this research context would have similar reactions to images of carousing, especially when one such image was identified as a user's profile picture. I also based these questions on conversations that I had with my own classes when we discussed the rhetorical applications of social media sites, particularly what they considered to be tropes of social media behavior.

There were a total of 12 questions that I identify as designed to look at how students conceptualize audience—one of the key components of rhetorical analysis, and, as indicated by many discussions of social media use in the classroom, one of the main reasons why such study is often justified (i.e., the use of social media in the classroom can help students understand the complexities of audience). Two of these questions were more explicit in this aim, asking students to identify the reasons why they typically post content on the sites, and what audiences they explicitly consider when they post. Six of the questions were designed to measure responses to sample posts on four social media platforms (Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, and Instagram). The remaining four questions asked students to envision their response to an image (Figure 2) when viewed from multiple perspectives, that of a male college freshman, a female college freshman, the parents of one of the pictured individuals, and a prospective employer. All survey questions can be viewed in their entirety in the appendix.

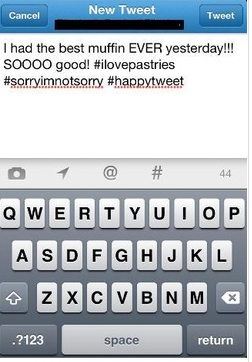

As noted, I developed the survey questions as a response to both Fife's (2010) article and to conversations that I have had with my own students about certain material that might constitute stereotypical social

media practices: behaviors that my students identified that caused them to make a judgment about that particular user. These identifiers included users who seemingly post for no reason other than to elicit a response,

individuals who use their social media platforms to "brag" about certain activities or proclivities, and users (particularly females) who post "selfies" in varying states of undress, again in an attempt to solicit

comments[2]. I therefore created mock tweets, statuses, and images that I felt were emblematic of these particular behaviors.

Instagram is an image-based social media site in which

users post pictures and, in a manner akin to Twitter, are "followed" by other individuals, whereas Pinterest, while also primarily image-based, allows users to create "boards" based on interests or categories—an

example would be a board called "Dream Wardrobe" in which a user posts images from online catalogues, websites, other Pinterest users, etc. of items of clothing that they find appealing. Since both Instagram and Pinterest

are still gaining an active following, with a smaller base of users than both Twitter and Facebook, I included only two questions that featured mock posts from these sites, one that showed a "pin" of an expensive-looking

purse (Figure 3), the other an Instagrammed picture from a tropical location (Figure 4).

For each of these mock posts—including those from Twitter and Facebook—I asked the participants to identify the adjective that they believe best describes the individual who posted this content. I provided four adjectives that could feasibly be applied to each mock post, including the previously mentioned picture of three college students with alcohol paraphernalia (Figure 2).

For example, for a mock profile picture on Facebook that featured a picture of a woman wearing a bikini (Figure 5), I asked students to choose (imagining that this woman was one of their friends) whether they would describe her as "friendly," "vain," "annoying," or "outgoing." I also included a fifth option that gave participants the opportunity to opt out of answering the question if they were not familiar with Facebook. All of the questions pertaining to a particular social media platform, therefore, included a range of adjectives that users could choose from that indicated how they would likely perceive an individual who included this content on their own profile(s). I chose these particular adjectives based on their applicability; I felt that they were all reasonable ways to describe each hypothetical user who created that particular post. Although there are hundreds of adjectives that could have been applied to each mock picture or text, my goal in allowing participants to only select from a set number of descriptors was to limit the number of possible responses. I recognize, however, that by providing these adjectives, there exists the possibility of skewing the participants' responses to the posts, as they certainly could have come up with other ways to describe the hypothetical social media user. My decision to include these particular adjectives certainly affected the conclusions I describe here, as the use of other descriptors could have led to markedly different results.

The point of requiring participants to choose from these particular sets of adjectives, however, was to ascertain the level of agreement. Referring back to the image of the bikini-clad woman (Figure 5), would the students universally select, for instance, "vain" over the other listed adjectives to describe the woman who used this image as her profile picture? I offer this notion of consensus as a means to attempt to understand how this particular audience of first-year composition students perceives the content: If there is an accord in chosen adjective, this can perhaps be used to justify a claim that these students come inherently to a recognition (i.e., that using a bikini-clad picture as a profile choice is a vain act). However, if no such consensus exists, then this might suggest that the way students respond to social media is more complicated, perhaps indicating that—to be aware of its potentially rhetorical function—students must be guided to an interpretation of the content from a variety of perspectives. The final four questions, pertaining to the image of the alcohol-consuming youth (Figure 2), therefore sought to measure whether there is any consensus when students are explicitly asked to consider such an image from a variety of different audience perspectives.

The interviews, as previously noted, were audio-recorded and then transcribed. They were then categorized for particular themes; specifically, these responses were coded for content that demonstrated implicit awareness of rhetorical composing processes. As such, the interview questions were designed to supplement the survey content by determining which social media sites students use and the frequency of that use, to ascertain whether and how students construct the rhetorical situation, and what references were made to Lloyd Bitzer's (1968) notions of exigence, audience, and constraints. An added goal of the interviews was to see if students, if they were users of multiple sites, would articulate different understandings of audience and/or reasons for why they engage with that particular social media platform over others. Again, if social media can be used in a pedagogical context, I offer that it is important to understand the ways in which students speak about and conceptualize social media, especially as the influence of these sites continually expands, thus shaping the ways in which students write in a digital setting.

Survey Results

Sixty-three participants identified that they were enrolled in the second section of the two-course first-year composition sequence, whereas only eight participants indicated that they were enrolled in the first section of the course. When asked to identify the social media sites that the participants used (they were asked to check all the sites that they operated profiles on), ninety-seven percent of students indicated that they had Facebook profiles, while seventy-eight percent had Twitter accounts. Fifty-eight percent of participants used Instagram, 42% used Pinterest, 16% had Tumbler accounts, and 12% used Google+. Fewer than 10% of participants identified as having either MySpace, LinkedIn, or "other" social media accounts. Although Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram were the most popular sites used by the participants, the relatively high percentages indicate that the vast majority of participants operate profiles on more than one social networking site. Additionally, the largest percentage of participants (34%) claimed that they spend an average of two to four hours on social media sites per day. Twitter was the network that the majority of the participants (42%) identified as using the most frequently, followed by Facebook (39%) and Instagram (14%).

A primary goal of the survey was to discern how students perceive the notion of audience when using these sites. When asked what their main reason was for posting or sharing content on a site, 57% of participants indicated that they "want to share thoughts or images with other users on the Internet," while 26% noted that they "don't give much thought" to why they post. Only 10% indicated that they "want my friends to comment on or respond to my post." These results are perhaps interesting when considered in relation to the subsequent question that asked specifically what audiences users consider when they post on these sites: 77% think about their friends, 61% consider their family members, 19% do not consider what "anyone" will think about their posts, and 16% consider the opinions of "anonymous Internet users." The high number of participants that indicate here that they specifically consider how their friends and family might react to their posts is at odds with the majority response to the first question, which suggests a more generalized awareness of how this content might be perceived in the larger and immeasurable space of the Internet. This perhaps touches on the perceived differences in whether or not social media profiles are "public" (i.e., accessible to all Internet users) or "private" (accessible only to those approved by the profile owner). How conceptions of audience differ when considering the public versus private iterations of social media sites, however, are explored in more detail in the interviews with student social media users.

The remainder of the questions, as described previously, asked participants to react to mock Facebook profile pictures/statuses, tweets, a picture on Instagram, and a "pinned" image on Pinterest. The results of these questions presented very little coherent data: when provided with the four adjectives to describe the given image or text, there were only two questions that achieved a consensus of more than 60% (i.e., when a majority of individuals picked the same adjective to describe the fictional user that posted that content). The two questions that achieved such a consensus both pertained to the photo of the scantily-clad young people holding the cans of what could be perceived as alcohol (Figure 2). When asked to consider the photo from the perspective of the parents of one of the females in the picture, 64% of the participants indicated that they would describe the male pictured in the photo as "irresponsible." When asked to consider this same photo—but this time from the perspective of a prospective employer—80% indicated that they would describe the male in the photo as "unprofessional." The fact that there was very little consensus in the other mock posts perhaps suggests the variation in how students perceive these visual and verbal texts.

For instance, when presented with a mock tweet that extolled the deliciousness of a pastry (Figure 6), 46% of the respondents indicated that they would describe the author of the tweet as "obnoxious" while, in contrast, 39% indicated that they viewed the poster as "enthusiastic" (13% indicated that they would describe the user as "bored"). While, again, this absence of consensus cannot be perceived as universal due to a limited data set, this perhaps indicates the need for more explicit discussion when such technologies are used in a pedagogical context. If social media are being used to examine the rhetorical situation, students must be guided into thinking about these texts from multiple angles—these recognitions are not necessarily inherent. From this data, it can be extrapolated that students do have an understanding of how parents and prospective employers might perceive certain content—the notion that viewing images of scantily clad young individuals holding alcohol might be problematic to some audiences—but there is considerable gray area when students are asked to consider these texts from within their own perspectives as first-year composition students.