Our [Electrate] Stories

Explicating Ulmer's Mystory Genre

Marc C. Santos, Ella R. Bieze, Lauren E. Cagle, Jason C., Zachary P. Dixon, Kristen N. Gay, Sarah Beth Hopton, Megan M. McIntyre

Reflection: Megan M. McIntyre

1. What work does a mystory do?

The order of the discourses (career, first followed by family, entertainment, and community) is instructive: asking students to first examine their career discourse may act as an impetus to explore the value of other kinds of nonprofessional attachment and discover tools and dispositions forged by the community, family, and entertainment discourses/memories. The mystory project, then, challenges the disconnect between our professional and personal selves and brings these tools and experiences to bear on whatever comes next. For me, this exploration of the blurring of my professional and personal selves can be seen most clearly in my Obtuse Meanings page. Though this exercise is situated within the career discourse section, my reflections are decidedly family oriented: I tell the story of the first Christmas I spent with my estranged sister. At the bottom of the page, I muse about the connections between this very personal memory and my career path/research interests. The answer, I decide, is that these familial experiences with loss and reconciliation have attuned me to particular theoretical positions: "These calls for affective attachment and caring for those not-yet-part of the collective sound the same as a phone call announcing the arrival of an always existing but not yet known member of the family." The mystory requires, in my experience, examinations of our actions, motives, and dispositions in such a way that these kinds of seemingly unlikely connections reveal themselves and (hopefully) alter the way we respond to questions/problems.

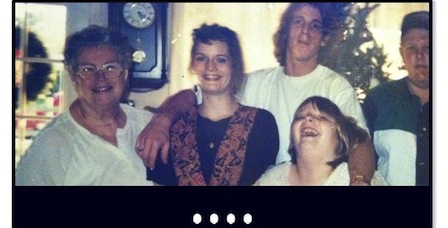

The mystory project also suggests an altered view of agency. The exploration of the discourses that shape us works as a kind of network analysis. After composing a mystory, it’s difficult to argue that I’m a wholly rational, autonomous subject; instead, I’m revealed as a compilation of memories and forces, at least partially dependent on others for my identity and agency. In short, I’m not sure there’s any such thing as a mystory or individual agency; I’m always already part of some “we.” And as such, my responsiblity for others becomes of the utmost importance: If I'm the one in charge of how the stories of my childhood—which include my parents, siblings, and fellow church members—I'm also the one who must constantly question how I've represented those others. I was particularly cognizant of this in my Family and Community discourses, where other people are the main focus of my discussions. My relationship to these others is vital to understanding how I came to be as I am, but I constantly struggled with the ethics of my representations of those relationships.

Gregory L. Ulmer’s call for us to trace our histories seems particularly potent in view of his goal of self-discovery [By calling his goal self-discovery, I don’t mean to suggest that we come to know some essential self; rather, we trace the forces that shape us and in doing so, discover our (always multiple) selves.] Though Ulmer’s goal in Internet Invention (2003) isn’t communal, he noted, in Electronic Monuments (2005), that electracy is meant “to do for the community what literacy did for individuals,” to send the community “to school collectively” (p. xxvi). The mystory is the first step toward our collective electrate education.

2. Does the mystory realize Ulmer’s aspirations?

Ulmer’s purpose, I think, is to give students the tools to do exploratory surgery of sorts: the mystory asks you to open old wounds in order, hopefully, to give you insight into the broader patterns of your life. In the introduction, we compare Ulmer’s work to a revitalization of expressivism, a way of reimagining the expressive search for personal truth and insight for postmodern subjects and digital contexts. I think this analogy is spot on: Donald Murrary, in his 1972 “Teaching Writing as a Process Not a Product,” argued that the value of teaching writing lies not in the writing produced but in the “search for truth in which [the writer] is engaged” (p. 5). The same can be said of the mystory. Coding attractive web pages is the not the goal of composing a mystory; rather, Ulmer uses the double-disorientation of Internet Invention’s complex theoretical content and the unfamiliar syntax of HTML and CSS to force writers into new territory.

This new territory was both practical—I had no experience with coding—and ontological. And in terms of the latter, Ulmer's method was certainly successful in terms of requiring me to confront the forces by which I was formed: even though there were times I censored myself to protect other participants in stories I considered telling (particularly in my Community Discourse's Quest Schemata, where I omitted names to protect the innocent as well as the guilty), the very act of considering those stories, those other people, revealed a pattern of values that altered my understanding of myself. The process of composing the mystory offered me a way of understanding my professional and personal selves that was totally foreign by blurring the lines between what I had thought were disparate versions of myself.

3. Can/should you learn Ulmer while learning HTML and CSS?

The short answer to the question of whether it’s possible to grapple with both the theoretical complexity of Ulmer’s work and the syntactical challenges of learning a new language is no. But I think that’s Ulmer’s intention. Students, especially graduate students, have learned how to write within the system: we know the answers or at least have a sense of the expectations of professors and assignments. We’ve learned to be critical readers and writers. Ulmer’s project requires a different approach; mystories aren’t meant for explicit critique or argument. Without the kind of confusion caused by this unfamiliar language, however, it would have been easy to fall back on the kind of writing with which I am most comfortable. Instead, I was forced to find a new way to approach writing assignments I didn’t fully understand in a medium I didn’t understand at all.

4. Should a mystory be public or private?

I chose to leave my mystory on my public, professional site. Largely, I made this decision because I think it has value in terms of understanding my pedagogy, dissertation, and other aspects of my professional persona. But I also made this decision because I think it’s valuable for others to know that I’m not ashamed or afraid to discuss challenging moments, to know that I see the value of these memories. The mystory acts as a statement for me, an acknowledgement of the difficult circumstances in which I grew up and a rearticulation of my intention to use those negative experiences for positive ends.

I think this project has value as a punctum, as a way of challenging the kinds of distance we pretend to have from our research. But this sting is often (always?) painful, so using this project in a grad class means, I think, acknowledging the pain and striving for a balance between the coding work and the practice of particular skills and the emotional/psychological work (therapy?) this project requires.

Looking at the completed mystory, though, I wish I had taken a few more risks in terms of the stories I told. Going through the process illuminated connections to other, more challenging moments that I’d like to connect to the pattern of values I discovered. As my mystory progressed, I got better at dealing with difficult moments and memories, especially in my Community Discourse, and these practices (of pairing quotations and images and allowing the viewer to make assumptions, of using callout boxes and questions, even the use of pronouns—in the Quest Scemata, for example) allowed me to be a little more honest without leaving others (unknowingly) vulnerable in a very public space.

5. What else do you want to say?

I’m not sure I was quite prepared, emotionally, for the requirements of this project. Reading about postpedagogy’s valuation of the affective dimension, about the concern of feminist pedagogues with making space for emotion and irrationality in pedagogy, does not necessarily prepare one for facing many of the best and worst moments of one’s life. Remembering is hard; I need to remember that.

6. What part of your mystory is your favorite?

Though many of the punctum moments come in my Career and Family discourses, my favorite pages are the ones in my Entertainment Discourse. Part of this is nostalgic: I still remember how much I loved Where the Sidewalk Ends and how much I wanted to be part of the family on Full House. Mostly, though, my love for these pages has to do with the ways in which my text mixed with text, images, and videos from my favorite book, television show, and movie. I find this mixture interesting theoretically because of the ways in which the message of each component depends on the others for meaning(s). But I also think that composing these pages was the moment I realized how composing for the web (because of the affordances of images, videos, hyperlinks, etc.) altered my conception of composition broadly. Network technolgies have fundamentally altered the way that things are written and read in digital spaces. And I can do so much on the web that I can't do with pen (or word processing program) and paper.