Our [Electrate] Stories

Explicating Ulmer's Mystory Genre

Marc C. Santos, Ella R. Bieze, Lauren E. Cagle, Jason C., Zachary P. Dixon, Kristen N. Gay, Sarah Beth Hopton, Megan M. McIntyre

2. Did you experience an aha moment during your mystory process?

In reflecting on our experiences with the mystory, both formally and informally, many of us described what Jeff Rice (2007) described as aha moments. Participants understood the aha moment to be a point at which the mystory process invokes a knowing of thyself, in the Socratic sense of revelation or introspection (and with all of the philosophical implications that that bears). Interestingly, when asked about the aha moment, participants all responded with answers that interrogated identities, both our own and those implicated by our mystories. For some, aha moments were crucial insights that led us to recognize the ways in which our identities are tethered to others. Conversely, other participants focused on the multiple ways identities were represented and mediated through the different discourses.

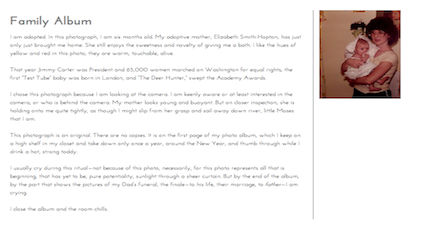

Both Ella R. Bieze and Sarah Beth Hopton explained that their aha moments occurred when they were most aware of other identities that haunted their mystories. For Bieze, these identities—specifically, those of her family—were so intimately linked to her own mystory that each assignment of her project reflected her role within her family:

Even in assignments in which I don’t include explicit references to family, like my Illumination, in rereading them I saw that my family still had a presence there: the moment I describe in my Illumination takes place as I am flying between Boston, where I was living at the time, and Oregon, where my family lives. (Bieze)

For Bieze, recognizing the ways in which her family has shaped and continues to shape her identity was a revelation that struck her most poignantly as she created her Wide Emblem page:

So I suppose the creation of my Wide Emblem was my "ah, ha" moment in that I realized that in creating my mystory, my family is what I had been circling around the entire time, and what I will probably continue to circle around for the rest of my life. (Bieze)

This revelation influenced her decision to keep her mystory private, as well, since, like Megan M. McIntyre in question 5, she understood that her family was implicated in all of the stories she explored.

While Bieze's aha moment came when she recognized the others who were present in her work, Hopton’s moment came when she considered the others who were absent. For Hopton, the mystory lacked a public audience, and this problem led her to imagine an audience as she engaged in the process. Hopton's aha moment, furthermore, was the result of critical thought and reflection, and not necessarily a “surprising” (Rickert, 2007) revelation:

As I critically analyzed the process of composing the mystory, what struck me as profound was my need to invent an audience and to create a sense of imagined dialogue so that I could use the text as an act of participation instead of a text that contained mere observation and reflection. (Hopton)

Hopton pursued a sort of dialogic, interactive process for her mystory project, which was bound up in her social epistemic focus:

I was creating an imaginary discourse community in which the political work of the mystory might unfold, provoke, engage, and ultimately resolve. Without this community—imaged or real—and the reading, dialogue and critical inquiry it facilitates, I felt the mystory lost its potential power as a text through which I might create a new cultural narrative instead of simply maintaining the static codes of a classroom assignment. (Hopton)

For Hopton, the mystory was an overtly political project, which speaks to her need for an audience as well as her desire to make the mystory public. Whereas Bieze felt responsible for protecting those who were involved in her story, Hopton felt obligated to invite dialogue with these others—and to respond to them.

For others, aha moments also centered around identity, but with a particular focus on the ways that the mystory interacted with how they saw themselves. Lauren E. Cagle, Jason C., and Kristen N. Gay's aha moments each depict a view of the self as elusive and perhaps fractured. Knowing thyself in the mystory genre meant seeing the many ways that the self could be represented, or resist representation. For Cagle and Gay, juxtaposing the four discourses in the mix of the mystory meant cultivating a new way to know thyself, and it was this that stuck out most to them in retelling their aha moments.

For instance, Cagle remarked on how the process of composing a mystory helped her to revisit the concept of motion as a part of her identity:

Creating maps for Mapping Home, Mapping the Popcycle, and Pidgin Signs gave me a new view of my erratic course across cities, states, and countries. The lines on those maps connecting my places represent what I have brought with me every time I change. They show that my moves, physical and intellectual, do not necessarily mean a fundamental change in myself. I can be and stay myself while shifting course. I have been and stayed myself while shifting course. But I have also left much behind, in childhood and in my many homes.

For Cagle, the mystory’s breakthrough, aha moment came in realizing a way to connect different threads of her identity: she doesn’t have to invent a new coherent version of herself for every one of her numerous moves. In her case, it led to a view of these threads as ancillary to a more resistant image of herself over time.

On the other hand, Jason C.'s aha moment indicated that he sees his identity as multiple and fractured, which was made more apparent by composing with new media elements:

The most salient point here, I think, is not that someone viewing my mystory today will notice these [new media] elements and have a different reading, but rather that I had a different reading of my own experiences while composing the discourses because of new media. (Jason C.)

In this way, Jason’s mystory, as viewed through his aha moment, was a way to recognize the many identities that come to bear in online interactions.

Though Gay’s aha moment was also related to identity, it came in recognizing the ways the self can resist simple representation and symbolism. While constructing her Wide Emblem page, a pattern emerged:

I realized that, in selecting these successive words and pictures instead of following the directions, I was refusing to make myself into a symbol. The images and the phrase actively resist becoming an easy symbol that means something. I do not trust symbols, and I did not want to reduce my experiences to one. At the end of my mystory process, I did not want to find my “problem” that guides my career, family, entertainment, and community discourse. I wanted to see the web of problems that encircle and shape me, and I wanted to dwell with them uncertainly. When I look at these images and read the phrase, I experience something—uncertainty, confusion, excitement, and resilience. I wanted to be constantly re/presented, not to represent myself. And that, I think, was my approach to the mystory and my goal, if I had one.

Gay’s aha moment is unique in that it captures the difficulty many of us felt in making meaning out of the mystory. For her, though, a meaning cobbled together from the discourses was too neat, and she chose instead to dwell in the uncertainty of being re/presented through the mystory. In the end, Gay announced that “Ulmer can’t fix me.” Her graduate project ambitiously aims to apply Gregory L. Ulmer’s revelatory project to a more supportive, professional, therapeutic environment.

Zachary P. Dixon and McIntyre declined to answer the aha moment question (both felt they had addressed this question in their other responses). Both also felt the revelatory dimensions of the mystory emerged through cumulative process rather than flash reason [as Ulmer (2012) frames it].