In the spring of 2012, 21 students signed up for Rhetoric 312, Writing in Digital Environments. While interpretation of just what constitutes “writing” and “digital environments” is up to individual instructors, RHE 312 is a lower-division course taught using networked computers and focused on using, interpreting, and analyzing traditional and emerging technologies

(Department of Rhetoric & Writing, 2012–14). All students who enroll in RHE 312 must have at least passed RHE 306, the “Composition 101” of The University of Texas system. For some of these 21 students, RHE 312 was the first exposure they had to college writing with digital technologies.

“Writing,” in this sense, referred to a variety of inscription technologies across many modes: verbal, visual, aural, procedural, haptic, and kinesthetic. The course was designed as a type of survey of contemporary expressive technologies, exploring the affordances and constraints of each. Students learned about digital discourse communities and finally presented an argument to an audience of their choice. The hope was that students would leave the course with a greater awareness of not only the communicative power of digital media, but also some of the limitations it imposes upon its users and producers. For this aim, students covered a range of texts that addressed both theory and praxis. All the readings for this course can be found in the left and right columns of this page, and full citations are provided in the References.

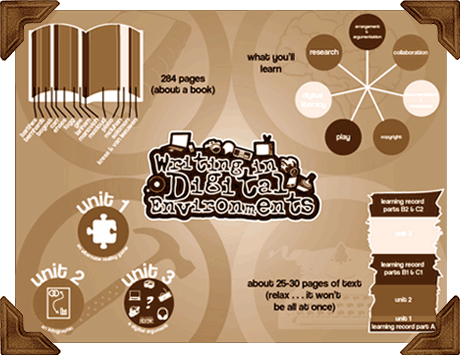

.The course covered three major units, with each culminating in digital composition and textual reflection. Battle Lines was the first of those units, and thus was designed to introduce students to software and techniques. Using the skills learned in Battle Lines, students later created an infographic for Unit 2 and a researched digital argument for Unit 3. The Digital Writing & Research Lab at UT admittedly provides an environment outside of the norm, as the program has been evolving since 1985 and receives support from the Department of Rhetoric & Writing. However, we believe that most of the principles taught in Battle Lines can be applied using open source software and collaborative exercises.

Keith Aoki, James Boyle & Jennifer Jenkins

Tales from the Public Domain:

Bound by Law?

Roland Barthes

Rhetoric of the Image

Stephen A. Bernhardt

Seeing the Text

Ian Bogost

The Rhetoric of Video Games

Nicholas Carr

Is Google Making Us Stupid?

The Computer History Museum

Remix:

Lawrence Lessig on IP in the Digital Economy

Hanno H.J. Ehses

Representing Macbeth: A Case Study in Visual Rhetoric

B.J. Fogg

The Functional Triad:

Computers in Persuasive Roles

James Paul Gee

Learning and Games

Gunther Kress & Theo van Leeuwen

Colour as a Semiotic Mode:

Notes for a Grammar of Colour

Richard A. Lanham

The Implications of Electronic Information

for the Sociology of Knowledge

Lev Manovich

The Language of Cultural Interfaces

Scott McCloud

The Vocabulary of Comics

&

Blood in the Gutter

Plato

Phaedrus

Marshall McLuhan

The Medium is the Massage

Martin Solomon

The Power of Punctuation

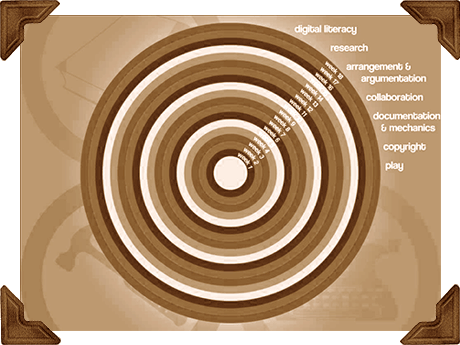

Given that students were being asked to create multimodal compositions, it made sense that the class materials followed a similar process. Click on the images below for the course’s infographic syllabus or the interactive course schedule.

The infographic syllabus was divided into four quadrants: reading, learning, writing, & making.

The course schedule follows the same logic: hovering over each week’s ring brings up what students will read, write, & make.

One of the struggles of implementing games in the classroom is working within the more traditional forms of assessment. After all, (most) American universities require that students receive some form of grade for the course, and such a requirement can sap the fun out of any assignment. While there are winners and losers in agonistic games, alternate reality games tend to foster more collaborative efforts among players. We felt to grade students on their performance in each level would unduly emphasize the product rather than the process.

In order to be conducive to gaming structures, the form of assessment used in this course needed to require and allow students to explore their own educational processes. Assessment for the course thus occurrred via the Learning Record Online, a portfolio system adapted by Dr. Margaret Syverson of The University of Texas at Austin. The LRO asks that students record and reflect upon their work, with a focus on demonstrable skills and knowledge. While a full discussion of the Learning Record is beyond the scope of this project, we hope the reader will explore this assessment technique further through the Learning Record Online’s website.

The Learning Record encourages playful engagement by removing the promise (or threat) of a grade for individual assignments and placing more emphasis on the process of working through the clues. At the midterm and final, students analyzed their own work for evidence across six dimensions of learning (the ways students learn) and seven course strands (what we wanted students to learn). In order for student-players to have evidence to analyze for the Learning Record, it was necessary that they worked through the clues. When the end goal of the course is to present evidence for what you’ve learned, correct answers count, but much less so than continued engagement and experimentation with the material.

more (confidence and independence) is better.In a science class, for example, an overconfident student who has relied on faulty or underdeveloped skills and strategies learns to seek help when facing an obstacle; or a shy student begins to trust her own abilities, and to insist on presenting her own point of view in discussion. In both cases, students are developing along the dimension of confidence and independence.

performanceor

mastery,we generally mean that learners have developed skills and strategies to function successfully in certain situations. Skills and strategies are not only specific to particular disciplines, but often cross disciplinary boundaries. In a writing class, for example, students develop many specific skills and strategies involved in composing and communicating effectively, from research to concept development to organization to polishing grammar and correctness, and often including technological skills for computer communication.

behaviorism? These are typical content questions. Knowledge and understanding in such classes includes what students are learning about the topics; research methods; the theories, concepts, and practices of a discipline; the methods of organizing and presenting our ideas to others, and so on.

In our original proposal for Battle Lines, we ambitiously outlined 28 goals the game would teach. After a year of revision, though, we pared it down to these 18 goals. By playing through the clues we devised, students would learn: