DISCUSSION

The text to the right describes the results of the captioning activity as it was implemented with the trial class as well as a discussion of the student survey and reflection results. This survey prompted students to reflect on their own dispositions towards language difference.

Student Captions: Standardization, Diversity, and Avoidance

Students produced an expected variation of captions, especially for non-standard words or phrases. The captions produced by students frequently differed from the captions encoded on the DVD, but, as mentioned by some students in their reflections, the captions on the DVD are often no more “correct” than other possibilities (see appendix for the official DVD captions). In fact, the closed captions provided on the film vary across different releases of the film, and the English subtitles on the film may differ from the Federal Communication Commission's dedicated line of data (in Line 21) for closed captioning of analogue television transmissions. Again, this is to say that the “official” captions are not authoritative or more “correct” than student captions, but only a base of comparison that has been produced more or less in line with national captioning standards and guidelines.

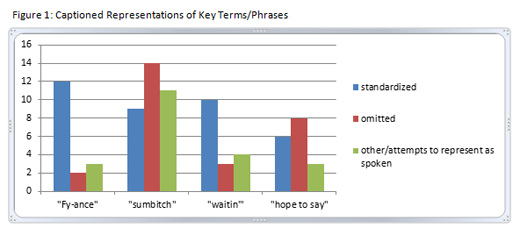

Yet the differences across captions are rhetorically and politically significant nonetheless. In particular, for this experiment I looked at differences in the representation of four key words or phrases that I hypothesized would be most difficult to understand/represent or that were recognizably non-standard: "hope to say," "sumbitch," "fy-ance," and "waitin'." The representations varied, as discussed in the introductory video, but the trend across these phrases was towards standardization, with 63% of respondents standardizing fy-ance as either fiancé or fiancée; 26% of respondents writing out son of a bitch; and 59% of respondents writing waiting for waitin’ (see Figure 1 below). Almost as common was the choice to omit these words or phrases altogether, though that may have been due to inability to keep up with the rapid typing as much as a rhetorical or otherwise strategic decision.

Though the sample size of this informal activity was small and therefore not generalizable, the student captions suggest that the two most common responses to non-standard or difficult-to-represent speech in this group were to attempt a translation to standard English or not to represent it at all. Representations of the perhaps unfamiliar phrase “hope to say” (used here to mean something akin to “I hope to say so” or “I hope not”) seem to support this conclusion, as the vast majority of students omitted this phrase or wrote the phrase as “wouldn’t say,” which is not a particularly obvious cognate. This suggests that students sought a more familiar phrase, often a more “standard” phrase, or, if none seemed available, neglected to represent it (see Figure 1 below).

Student Reflections: Representing Characters, Representing Selves

The students’ written reflections on this process complicate an interpretation of these results, as only three mentioned purposefully omitting parts they could not understand, though a significant number of students (more than half in the case of “sumbitch”) omitted the problematic word/phrase from their own captions. Most responses suggested that it was of central concern to caption everything possible, and ten made some suggestion that representing accented delivery was important because it showed character (though their interpretations of what the Southern American accent in this film means to viewers differed). One student reflected at length about the impact of representation:

With some of the closed captioning in the movie clip it took away from the roughness and crudeness of Hi's character. By leaving out "son of a bitch" you don't get the context of what he is calling Ed's fiancee, you also don't understand his frustration with the Reagan administration fully. This little saying provides a whole lot of information about Hi's character, and what he really cares about during these opening moments in the movie. I also feel the addition of having Ed mis-say as well as the captioning being misspelled for "fiancee" shows the education level as well as the type of characters we will be dealing with for the rest of the movie. It also shows that while Hi speaks fairly well and seems well educated he is a convicted felon, and Ed is supposed to be a respected and very well educated officer but she cannot even pronounce "fiancee" it creates irony between the two characters and their life stories as the movie develops onward.

This thoughtful analysis of the narrative stakes of standardization and representation might well be built upon to further interrogate this students' assumptions about language and identity, since the student is already attending to the rhetorical nature of these representational choices and considering the value of non-standard textual representations.

Only two students actively resisted non-standard representations in their reflections, writing

If you can put it in quotes, but if not use the right word, as apposed [sic] to slang, and put it in brackets. the meaning would still be clear and the message would come across better because there is no interpretation of the slang on the viewers [sic] end of the movie.

and

I represented everything in the proper way a word would be said ad [sic] didn't consider how they pronounced them.

These students represent what has been a common approach to language, which values the standard as "right" or “proper" (Horner & Trimbur, 2002; Horner, Lu, Royster, & Trimbur, 2011). The idea that the “message would come across better because there is no interpretation of the slang” reflects an assumption that standard English is, by contrast, a neutral medium not requiring interpretation.

By contrast, the majority of students instead emphasized the importance of representing accent to show “how people talk,” “that the speaker may not be well educated or signify that they are from a different culture with an accent,” “that it is more of a casual conversation or that the person often speaks in slang,” or “to be able to profile that character.” While these responses appear to value accent as an acceptable deviation or valuable marker in communication, they also clearly promote some of the same problematic assumptions about the value of standard English as set against "accented" speech. More specifically, these responses tend to dichotomize the “correct” way academic discourse asks students to write and “how people talk,” and to tacitly value standardized English as an unmarked norm. They assume, in other words, that standardized English is a transparent (and often superior) language construction, while accent or dialect is a marked deviation that shows non-normative “character,” especially lack of education. Problematic as some of these assumptions may be, though, they demonstrate that students understand language to be tied to power, and a conversation about the power of standardized English being unmarked and uninterrogated might follow fruitfully.

Again, though, the emphasis on the importance of accent described in many student responses was not reflected in the actual caption writing, suggesting a potential disconnect in the understanding of what standard or non-standard phrases look like in writing or some other difficulty in the caption-writing process. The idea that accent marks a speaker in a perhaps negative way as uneducated or “country,” cited in several responses, may have contributed to students’ resistance to captioning non-standard speech. In other words, the multicultural ideology of the 1990s that inadvertently whitewashed difference ("I don't see color") might lead some students to resist the profiling potential of representing non-standard speech, even while other students expressed the opinion that the descriptive power of accent is a particularly important reason to represent it.

At the same time, the rhetorical awareness that these students demonstrate in their attention to the specific narrative purpose of the film and its audience might have produced a troubling paradox for students producing captions within the classroom: namely, the production of texts for captions occurs in a non-academic venue where the stakes and expectations of non-standard speech tend to differ. Students may have felt compelled to produce more “standard” representations because the captions were produced in the context of a classroom. However, their explanation of these decisions in the reflection and survey suggest that the impulse towards standardization may transcend academic contexts.

Survey Results: Diverse Language Experiences as Resource

Clearly, these students took varied approaches to language diversity that each have political and practical consequences for their language flexibility and representational decisions. Perhaps most importantly, their interpretations of meaning seem to be strongly influenced by their own existing language experiences and resources. Some students discussed past experiences with closed captioning, others with accented speakers. One student specifically mentioned remembering “how I've heard people talk, in terms of [her] more ‘country’ uncle” and drawing on that memory to caption “sonovbitch” as she has “heard him call people.” This comment suggests the importance to students of drawing on past experiences to understand and represent diverse language users. We might wonder how having students purposefully engage with diverse language use as legitimate practice in our classrooms might help them build similar experiences to draw on and to become more flexible language users and communicators.

Of course, experiences in the classroom differ from and may not neatly transfer to contexts outside the classroom. The results of the survey questions, then, may be affected by the educational contexts that the questions discuss, such that students may have different expectations for language use in academia than elsewhere. The association of accent and dialect with lack of education is important here, and it may also explain why 35% of students said it was important for instructors to speak perfect standardized English to teach. However, only 12% agreed that it is frustrating to hear non-native accents spoken, while more than 40% disagreed or strongly disagreed that it is frustrating, suggesting that students were overall willing to engage with diverse language users.

Studies about student attitudes toward non-native English-speaking instructors increasingly show that students do not consider language difference alone as an important source of frustration. For instance, Athena Trentin (2008) found that much more significant than the problem of language itself was the problem of differing expectations about instructional strategies—how information is organized, how a classroom is managed, and how confusion and questions are addressed by the instructor. While the class under consideration here was small and the results are mixed, there were indications that students do not isolate language variation as the sole factor for assessing the effectiveness of communication.

In terms of language flexibility, while students were particularly split on whether it was the listener’s responsibility to make meaning when listening to a non-native speaker, the fact that a great majority did not find it frustrating to do so demonstrates some language flexibility. This flexibility may have been specific to the group studied, but it seems possible that increased exposure of native English-speaking students to different varieties of English in the news, popular culture, and the public domain at large has made students in the US more flexible than we may assume. While a work of this scope cannot do justice to the larger issue of language attitudes, we want to highlight that integrating activities that help students learn and use language negotiation in the writing classroom is both possible and pragmatically beneficial for our students, who are certainly aware of their position in an increasingly diverse country and increasingly connected, global world. Our students' willingness to engage in language negotiation—to attempt to understand and represent diverse language—might also be supported by the fact that students overwhelmingly enjoyed this activity, rating their agreement with the statement “This activity was enjoyable” at 4.1 on a 5-point Likert scale, with five indicating “strongly agree.”

Overall, the results of this experiment suggest that these students may want to be flexible language negotiators in spite of being influenced by a cultural pressure towards standardization and a notion of the cultural value of standard English as a marker of education and status within and beyond the academy. While the results of this informal pedagogical experiment are not generalizable, further studies might be able to better probe students' opinions on whether standard English is “clearer” or automatically “more correct” than non-standard uses and representations, while also providing more information about students' diverse language resources.