Part 3: The Next Generation (Kyle)

Obligations vs. “Useful Places to Be”

At the University of South Florida in Summer 2011, First-Year Composition Mentor Coordinator Megan McIntyre had a problem. While planning the two weeks of required orientation for new and returning FYC teachers, she knew that she needed to find a balance between introducing the firehose of information she wanted teachers to hear and allowing everyone the space to breathe between the blasts. As the fifth person to be in her position since the mentoring program was inaugurated, Megan had witnessed orientations that veered too much toward one side or the other—too overloaded with activities or too laissez-faire.

In a conversation with me, she described her solution this way:

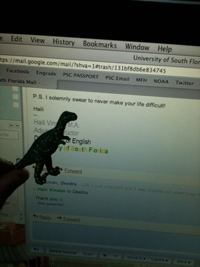

Megan-useful-places-to-be by kstedman[Transcript: “So our whole goal was that people would kind of create their own best schedule. And that there were these things that we needed them to do, but we didn’t want them to feel like obligations so much as useful places to be. And so giving them a reward—like a tiny dinosaur!—for going to those places seemed to kind of fit in with that spirit of independence and fun and attention to the community, as opposed to being such an internal, top-down model.”]

That’s right: a tiny dinosaur. One of the two main differences between the 2011 and 2010 orientation was the introduction of FYC’s the Day, subtitled “a delightful game for the enterprising instructor,” which offered instructors the opportunity to win, among other things, a cheap plastic dinosaur with custom sparkles added by the FYC staff. The other difference that Megan alluded to was the opportunity for instructors to “create their own best schedule” through an increased number of breakout sessions, making a large chunk of orientation model the structure of an academic conference. And to win the game, you had to attend breakout sessions; besides the other quests, you got a stamp for each that you attended. At the 2010 instructor orientation, 12 different breakout sessions were offered with some repeats for a total of 20 total breakout presentations. Due to that model’s popularity, this was expanded to 23 different sessions offered in 2011, delivered in over 60 total presentations.

Don’t miss that: to ensure that teachers attended more sessions—in effect, to put a sort of control on their personal agency by guiding them to where she thought they should be—Megan and the rest of the FYC staff (including me, Kyle) gave orientation participants more choices. By giving teachers choices, we also guided them to where we wanted them to be. Megan’s observation that she wanted the various orientation sessions to be “useful places to be” reflects an important angle on how we create meaningfulness among communities of teachers. Among our FYC instructors—consisting of graduate students in literature, creative writing, and rhetoric and composition at multiple levels, along with visiting instructors and adjunct faculty—it’s difficult to find a common system of beliefs and interests that will oil the gears of required group activities like orientation. Each individual comes to each session with his or her unique perspectives and goals, leading to as many meanings being created as there are people in the room. While a new M.A. student in literature who has never taught before might sit in rapt attention at a session on teaching peer review, a returning adjunct instructor may be thinking that he ought to be the one leading the session.

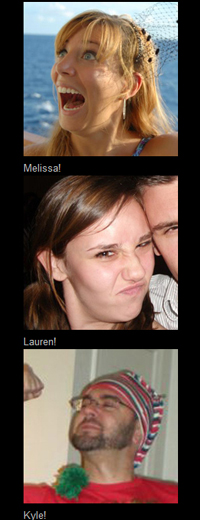

But anyone can get behind sparkles and dinosaurs—and I’m only partly joking. The innate silliness of the game, along with the irreverent tone of the quests, game website, and images of the quest-givers, has the odd effect of drawing people together into a common vision, or at least as close as this group is likely to get to one. Megan had thoughts on this as well:

Megan-having-fun by kstedman[Transcript: “You’re never sure if you’re allowed to have fun at these kinds of things. Right? So I think it was an attitude switch, and it was unexpected. Plus, I think there’s a fear, in graduate school—everybody’s trying to make sure that you’re not the stupid kid in class. And there’s a sense in which a game like this makes you more vulnerable because you are having fun, and because you’re asked to do some things that are silly and post pictures of yourself doing silly things.”]

Instead of seeing orientation sessions as a chore to endure, there’s at least one reason to see them as “a useful place to be”: the opportunity to win big.

Agency: “You’re in it to Win”

In the end, FYC’s the Day was a tie; two players absolutely cleaned up, each completing all but one of the quests. I was unable to schedule a conversation with one of the winners, an incoming PhD student named Rondrea Mathis, but I did speak with Jamie Cooper, a third-year adjunct instructor, who described her initial uncertainty about the game:

Jamie-In-it-to-win by kstedman[Transcript: Well you have to understand that as a rule, I’m not a real competitive person. But I think it’s because I’m keeping my competitor in check, and the only way to do that is to not compete. Because you saw, once I got in, I was totally in. Well yeah, if you’re in it, you’re in it to win—why play around?

And actually my daughter, who was there with me the first day and saw, and, “Oh, this is so cool!” Cause she’s a student here, a junior, so, it’s like, “Mom, you’ve gotta do this!” It’s like, “Oh come on, really, I don’t want to do this.” And really I’m kind of an introverted person and kind of shy, and this is like, “Ohhh. . . .” But she convinced me to at least do the first couple of things.

So we went over—and you know, with the phones and everything, the pictures are so easy—so we went over and took the first pictures. And then that was it! Then I just had to win, after that. Well, that and the prize was a Starbucks card, and I’ll do pretty much anything for a Starbucks card.]

The answer to her question “Why play around?” is clear to Jamie: because it changed her relationship to her teaching community. Again, a paradoxical logic is at play here: By adding something new to her orientation experience (the game), and thus seemingly giving more of her attention to something beyond the content of the sessions, she found herself more engaged in the orientation event. This reminds us—as writing program administrators, as teachers, as rhetoricians, or simply as innately social creatures—that the simple transmission of content and meaning from one person to another is the dream of idealists. Instead, our learning is wrapped up in the contexts surrounding our meanings, including all the daydreaming and motives that are simmering beneath our surfaces.

Perhaps one way to think of individual agency in the midst of groups is the degree to which one perceives that options are available, even if those options are “invisible” games that are layered onto mundane experiences. Speaking more about her decision to play the game, Jamie told me:

Jamie-understood-the-purpose by kstedman[Transcript: Once I totally understood the purpose. . . . As an adjunct—I mean I know this was for TAs and all of us—but as an adjunct, especially one that works a lot in the evening or whatever, I feel very disconnected and out of the loop. So once I understood that it was . . . to help us get connected. So then I kind of took on, “Maybe, well it’s—this isn’t really for me! It’s for the new TAs, and the new kids.” So I was kind of seeing it as kind of a gratuitous thing. It’s like, “Who are you kidding? This is for you too, you need to get connected, this is awesome!”

And I think that was the thing I liked the most about it, even beyond the Starbucks card, was I finally felt like I was part of the community. So it really helped: it forced me to talk to people, find people, see people, do things.]

It sounds at first like an illogical jump, from feeling somewhat aimless in the FYC program to feeling the agency of an individual who is shaping her community experience, when no real circumstances of her orientation were changed. FYC’s the Day functions much as if players put on colored glasses to view the world differently—or perhaps the computer-enhanced contact lenses of science fiction that overlay the world with marked-up data and opportunities. The change is in the viewer’s mind, not in the actual experience of the world—that is, until the player begins enacting gameplay and creating real connections by completing quests. Jamie experienced the same orientation content that non-game-players experienced, and yet she moved through the sessions/game levels with a power she wouldn’t have otherwise had.

Conclusion

If Bogost (2011b) is right, and “-ification is always easy and repeatable,” then these two games may not be examples of gamification. Neither was particularly easy to create, and while one was heavily based on the other, the particular situations where each was deployed led to a number of situational adaptations in game design. At least to us, neither game felt emblematic of the problems of gamification: They weren’t lazy or like the marketing gimmicks that corporations tack onto products to appeal to a new demographic.

Yet we continue to see these efforts as examples of what the concept of gamification can add to experiences. In our cases, that addition came in terms of agency and community, but there’s no reason that the added value of gamification needs to stop there. The usefulness and danger of a term is that it can inspire others to consider how that term might augment experiences in other situations; our hope is that other teachers, writing program administrators, and confused graduate students far from home can latch onto the concept of gamification to begin a heuristic process of wondering, planning, and gaming. In the spirit of Bogost’s critiques, we hope they’ll first ask, “Is this a place where a unique, complexly wonderful game should be added?” But after that, we hope they’ll ask, “What layers could be added to this experience, changing perception and reality for the better?”