Embodiment: Sensing Music through the Body

I begin by setting out the foundation for analyzing ASL music videos and incorporating them in accessible multimodal pedagogies. I first situate the contrasts between conventional music videos and more accessible ASL music videos. I then explore how Deaf composers perform the visual-spatial experience of music. Their performances and music videos are embodiments—or multisensory recreations—of how multiple senses engage with music in different ways. This section is designed to illuminate how the pulsations and movement of dynamic visual text embodies the sensation of music in the body.

By rhetorically analyzing how ASL music videos synchronize rhetorical meaning across modes, students can begin to re-conceptualize the affordances of modes and better appreciate how different modes can coordinate in reaching the senses. Borrowing from Gunther Kress’s (2005) discussions of the &;affordances” of modes, I show how we might focus on the potentials, not the limitations, for representation (p. 12). If students recognize that modes may have more potentials than limitations—if they sense that visual text can embody sound—they could develop their own rhetorical practices for accessing meaning through modes in the way that Deaf composers have created visual access to aural content.

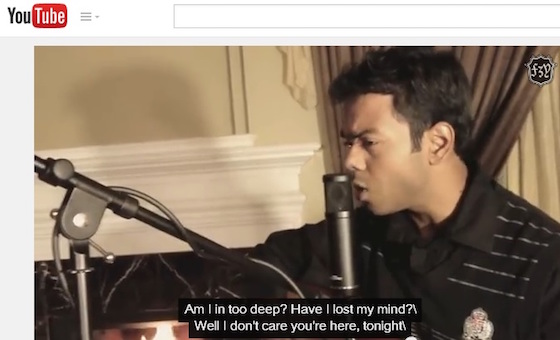

We can work with our students to recognize the differences between videos that use rhetorical and aesthetic strategies for communicating in multiple modes and those that do not. To find a point of contrast with Sean Berdy’s (2012) ASL music video, “Enrique Iglesias’s Hero in American Sign Language [Sean Berdy],” I searched for—and failed to find—subtitled versions of Enrique Iglesias’ “Hero.” I was left with a cover of his song by another individual (Yamin, 2012) playing his guitar. While the captions in this cover of “Hero” are relatively accurate, the static text appears as white letters on a black rectangular background and at times covers the lower portion of the singer’s face. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1: Screenshot from Fayez Yamin’s (2012) video, “Enrique Iglesias - Hero (Fayez Yamin cover)”

In addition, the textual lyrics are not synchronized with the audio. Two lines of the lyrics appear in the middle of the screen every few seconds in appropriate chronological order with the lyrics of the song. However, the textual lyrics disappear while the singer continues to sing the words. Then, a few seconds later, the next two lines appear, and they continue to be non-synchronous. This discord renders ineffective the coordination between visual and verbal words.

In the inaccessible version of “Hero,” the visual text is the only mode through which fully deaf individuals could understand the meaning of the song, and it is ineffectively produced. The deliberate pacing of Iglesias’ melody vanishes when two static lines of lyrics appear at once. The video shows how simply putting visual text on a screen is not enough to make meaning accessible. Each mode should be synchronized to create a multisensory, meaningful experience that can be sensed by different bodies.

In contrast, ASL music videos make the most of underutilized affordances of visual text and the spatial mode such as adding color, size changes, and movement to visual text. Visual text in their videos can expand or contract, be colored or bubbled reflecting the mood and spirit, or fade in and fade out in tune with the music. In ASL music videos, the visual text embodies the affordances of sound. Instead of instantaneously presenting every single word from a line on the screen at once, these compositions emulate the music’s pitch variations, energy variations, and perturbations in the air.

Videos with static subtitles could be presented in the composition classroom as a contrast to ASL music videos. Students could discuss ways to improve upon the practices in traditional videos and design ways to make meaning accessible across different modes. Students could contrast these videos with ASL music videos to recognize how designers can coordinate different modes—visual, gestural, spatial, and aural—to reach multiple senses.

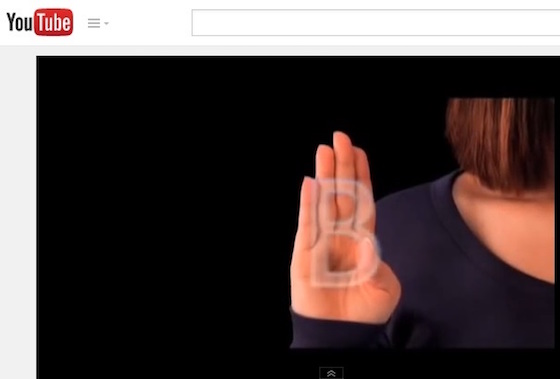

Figure 2: Screenshot from D-PAN’s (2008) video, “D-PAN ASL music video: ‘Beautiful’ by Christina Aguilera”

Artful and strategic synchronization of subtitles and other modes in ASL music videos improve the ways that viewers can access the rhetorical message of the composition. Figure 2, a screenshot from D-PAN’s (2008) ASL music video for “Beautiful,” shows the handshape B visually overlaying the visual text B to intensify the rhetorical interaction of modes.

In contrast to inaccessible versions of “Hero” discussed above, the ASL music video versions of Christina Aguilera’s “Beautiful” and Enrique Iglesias’ “Hero” recapture the lyrical content of the song through creative use of dynamic visual text that embodies the visual-spatial experience of music.