I. The Crisis of Sustainability: Harry Potter and Global Warming

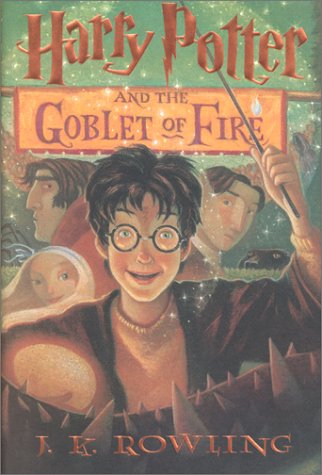

In the summer of 2000, Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, the third book in J. K. Rowling's wildly popular Harry Potter series, was published to great fanfare. As part of its efforts to promote sales of the book, the publisher entered into an agreement with web-retailer Amazon.com and delivery service company Federal Express to guarantee overnight delivery of 250,000 copies of the book beginning just after midnight on the day the book was released. Federal Express later boasted that these deliveries required a fleet of 100 airplanes and 9000 trucks.

In the summer of 2000, Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, the third book in J. K. Rowling's wildly popular Harry Potter series, was published to great fanfare. As part of its efforts to promote sales of the book, the publisher entered into an agreement with web-retailer Amazon.com and delivery service company Federal Express to guarantee overnight delivery of 250,000 copies of the book beginning just after midnight on the day the book was released. Federal Express later boasted that these deliveries required a fleet of 100 airplanes and 9000 trucks.

Although FedEx did not say how much extra gasoline and jet fuel was burned to make these deliveries, we might reasonably ask about the environmental impact of such a promotion. To state it more broadly, to what extent are our literate practices implicated in environmental degradation?

Scholars such as Harvey Graff, Brian Street, and Elspeth Stuckey have helped us see that literacy can be a tool for social control and political oppression as well as a vehicle for individual empowerment, but still it may seem odd to think of the act of reading and the desire to have a specific book to read as implicated in environmental degradation. Yet this example of the release of Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire begins to illuminate rather dramatically the complex ways in which literacy and literate practice – as well as technologies for literacy, including print and computer-mediated spaces – are directly and indirectly implicated in environmental degradation:

(1) For one thing, the technology of print in the form of the book is not only at the center of the practice of reading the story of Harry Potter for millions of people; that technology also has an obvious and often devastating environmental impact in the form of the destruction of forests, water and air pollution, and toxic waste generated in the production of paper and print materials. (2) The physicality or materiality of the "virtual" world of the Internet suddenly becomes apparent when we consider the electricity needed to power the computers that constitute the Internet. Since most electricity in the United States is generated through the burning of fossil fuels, including oil and coal, any use of electricity inevitably results in the release of greenhouse gases and other pollutants into the atmosphere. And because mining for coal and drilling for oil cause various kinds of destruction to the environmental sites where such activities are carried out, using electricity can also be said to contribute to degradation of the land as well. (3) As a vehicle for commerce, the Internet is also part of a vast economic network that includes numerous other technologies, such as trucks, jets, and packaging, that each result in various kinds of pollution or environmental destruction. In this sense, the World Wide Web is much more than a vast network of computers; it is part of a much larger web of connections that encompasses the physical environment we inhabit.

In short, literacy has material consequences; it is always in several senses physical. Moreover, electronic environments for literacy, such as the World Wide Web, are also physical environments and thus have material consequences as well. What's more, technology can help make this physicality of literacy "invisible" in the sense that technologies for literacy become seamlessly integrated into our literate practices and indeed into our ways of being-in-the-world. In this case, various computer technologies, along with print technology (the book) and transportation technologies, all form a kind of seamless web with far-reaching consequences that we don't always see. The click of the computer mouse to order a copy of Harry Potter from Amazon.com can seem a simple and almost natural act, yet it represents participation in this bewilderingly complex web of material connections that is anything but simple. And that participation contributes to the condition of our planet.

But there's still something missing from this picture: Literacy is not only material; it is also ontological. That is, literacy is implicated in our conceptions of self, which in turn help shape our ways of being in the world – which is the issue explored in Section 2: Plato Lives.