Haskell Springer, University of Kansas

[Note: The editors wish to thank the author for being willing to share a conference paper version of this project in support of this CoverWeb's focus on reflection.]

This is a commentary on my first venture into electronic editions. In about 8 months, with the help of 2 students, I produced a World Wide Web edition of Herman Melville's "Bartleby, the Scrivener" which I have now used in three courses. It's an example of a hybrid edition, or what some people call applied scholarship--an edition that attends to and records pertinent textual scholarship, that also incorporates other sorts of scholarship, but that exists mainly, though not exclusively, for the benefit of teachers and their students, most of whom seldom have access to the resources it offers. So far as I know, it's the only electronic edition in American literature so far to bring together a large number of pertinent secondary texts linked to the primary one as part of the edition's structure.

This work and its product are quite different from what I did many years ago as editor of Washington Irving's Sketch Book under the guidelines of the MLA's Center for Editions of American Authors. Then the product was its own reason for being, despite the barbs of Edmond Wilson. Few if any of us were asking then about the practical consequences, the costs, and the distribution of the kind of editing we were doing. But the 80s and the 90s have changed the ways in which many scholars regard texts. No longer are there "definitive" editions, critical editing has come under persuasive attack (by Jerome McGann, for example), and editorial focus now is often on variant texts and their social meaning. Furthermore, electronic editing is a new world. In talking about new paradigms and principles I could frame my remarks in the theoretical language of Jay Bolter, Michael Joyce, Richard Lanham, George Landow and others; but I think I should be more rhetorically direct.

I hope I'm making a reasonable assumption in thinking that virtually all English teachers have read "Bartleby," first published in 1853. The story appears in many anthologies for composition and literature as well as for American literature. Collections of short stories frequently contain it too. The story of the poor and friendless scrivener who says almost nothing but "I prefer not to"; who blankly stares at a blank wall; who, when queried, asks, "do you not see the reason for yourself"; is regarded today as paradigmatic--and makes an excellent choice for study in high schools and colleges.

My beginning principles or assumptions for this electronic edition of "Bartleby," some of which overlap, were as follows (None of them should be taken as explicit or even implied criticism of other electronic editing):

- It should be possible to combine the goals of a scholarly edition and a teaching one.The edition, whatever form it takes, should be shaped by the intended users as well as by other factors.

- My intended users are first my own students, next both teachers and students in higher education; and third, secondary school teachers and students.

- The edition should be usable by students without the necessary intervention of instructors.

- It should be useful to scholars whether or not they are thinking of pedagogy.

- The edition should be not only useful to its likely users, but attractive too.

- It should make use of graphics as well as of text, for commentary and not just as eye candy.

- It should be open to modification and correction--therefore a Web edition, and not on CD-ROM.

- Use of the edition should be free.

- It should supply ancillary materials otherwise inaccessible or difficult of access to the users.

- It should not only be the result of research and critical understanding, but should encourage research and some critical sophistication.

Here are some details.

The text is tagged in HTML, and came from Columbia University's aptly-named "Bartleby Project." Other textually-related material I adapted from the authoritative Northwestern-Newberry edition of Melville's Piazza Tales. The former is in public access, and since I reformulated the latter (which is a very small part of the whole), crediting its source and editorially departing in a few cases, no fees were called for. In this case HTML seems sufficient to the needs of the job. I'm also satisfied that the text is accurately and reasonably edited. I'm not satisfied, though, that my presentation of the textual analysis and history is much of an improvement over what printed editions do. I'll show you that in a moment.

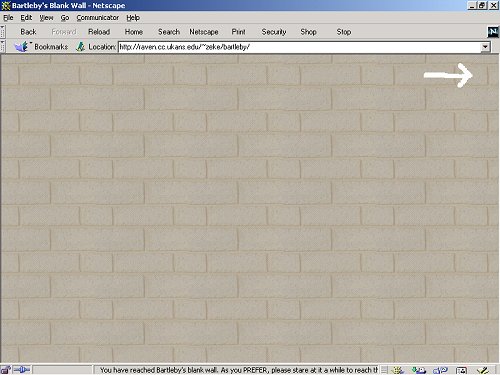

The first screen you come to when you type in the edition's URL attempts to insert the reader into the experience or the essential confrontation of the story before ever encountering the story itself. It's a brick wall.

That's an interpretive and pedagogical strategy, analogous to some sorts of front matter in printed editions--but with a major difference. Whether the user encountering this screen has read the story before or not, this wall asks for an engagement that is not just intellectual or analytical. It forces choice, one direction of which is non-action; it almost enforces emotionality, and it's meant to encourage uncertainty and perhaps a little frustration too.

The entire script that scrolls below the wall reads: "You have reached Bartleby's blank wall. As you PREFER, please stare at it a while to reach the mood of Melvillean and Bartlebyan emptiness implied by the story, Then/Or you may move on to the story and its entire Web site." The choice focused on in this message to users, an essential feature of Hypertext documents, of course, and therefore a critically important issue for editors of electronic editions, also happens to be at the heart of "Bartleby, the Scrivener," in theme and in plot, as preference comes into conflict with presumed necessity. It has to be addressed in the classroom. So "Bartleby" is a remarkably good text for the melding of form and content in an electronic medium.

The chalked arrow on the wall shows the electronic way beyond that wall for a reader, though Bartleby apparently could find no means by which to go around or beyond his own wall. Whatever the walls of the story represent--and critics have been ingenious in their many interpretations--in my function as an editor, I take the blank wall to be a metaphor of the limitations of codex editions. Just as with the arrow on the wall, then, electronic editing points the way to paths or means around and beyond the familiar brick-wall limitations of print editions. They include finality, great limitations in textual comparison, awkwardness in annotation, and prohibitively expensive illustration costs. Melville's story seemed to me to present a particularly apt opportunity to point out and embody the brick-wall limitations of print.

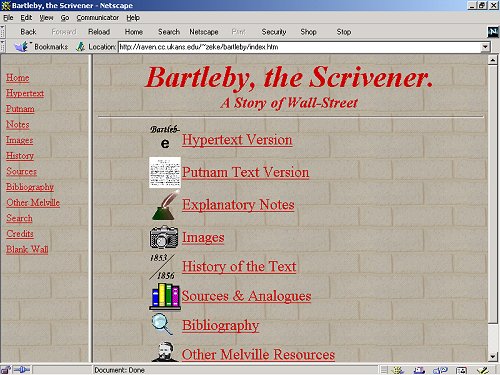

The arrow leads to this entirely different, informational home page

Now the mood and terms of engagement have changed. Reading this screen, one can see that this site contains two versions of the Text, a History of textual difference, explanatory Notes, pertinent Images, a section on Sources and Analogues, a Search function, and links to Other Melville resources. In addition, the Criticism section contains a huge bibliography on "Bartleby" (approximately 350 items), many hyperlinked to full texts of commentary (about 75 of them at this point).

I'll interject here in my remarks that these full-text chapters, sections, and whole articles by critics and scholars may be the edition's most valuable feature, pedagogically considered. They bring to the teacher and student, especially to those at institutions with limited library resources, immediate access to materials for both teaching and learning. As teachers, you can see, I'm sure, the possibilities for reading, writing, and research assignments.

But the weakness with this feature--and it is truly a weakness--is that the available critical texts are those in the public domain, or ones for which I sought and was able to get permission. Some very desirable critical materials are absent merely because their publishers asked too large a payment or denied permission under any circumstances (Note 1). Randomness is a factor here, then, and the user must be told that. Therefore, library research is an honest and appropriate supplement to research among the many full-text items on this site.

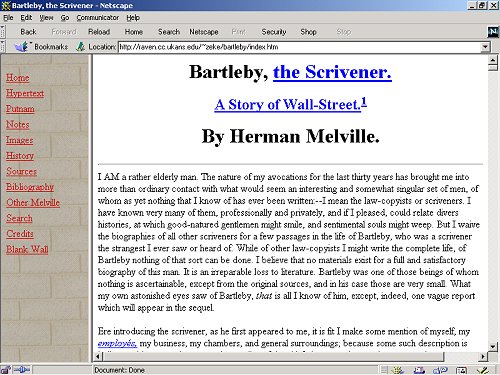

Returning now to the architecture of the edition: From here on out, the left frame remains on screen at all times as both a navigational convenience and an encouragement to the user to make choices. In the language of the story, it asks the reader to exercise "preference." Beyond the list of possible choices on this screen, this electronic "Bartleby" edition is full of links within a layered architecture, so that users have the choice of how far to follow an item and then where to go or not to go in pursuing their own reading preferences. A series of screen captures shows what I mean: The opening of the Hypertext version of the story shows the existence of an explanatory note about the story's title, and also shows that "the Scrivener" has a textual history.

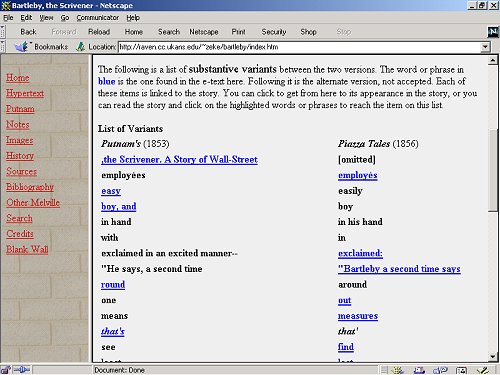

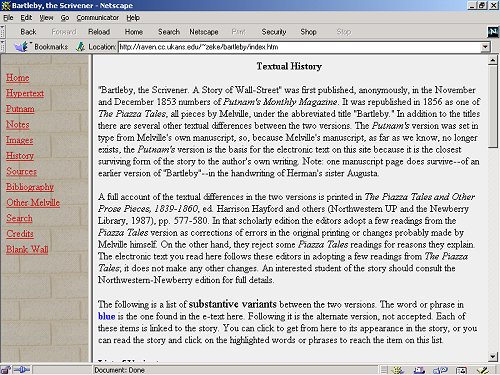

Next is the beginning of the list of substantive variants, showing that the story's title has a history, and linking the reader to each item in that history--in textual context, of course.

The text at the top of the page just seen briefly recounts the textual history and explains that full analysis is available in the scholarly standard, the Northwestern-Newberry edition of The Piazza Tales:

I'll pause again for a moment to comment on my own dissatisfaction with this Textual History part of the site. Though the lists improve on a printed version by using hyperlinks, these lists are just that, and their reasons for being are not made sufficiently clear right here to a student user. I'd like to find a better, more meaningful way of presenting the evidence of 19th-century authorial and editorial alteration, as well as the justifications for 20th-century editorial decisions. Though I know a way, it's very labor-intensive and may not prove pedagogically important enough.

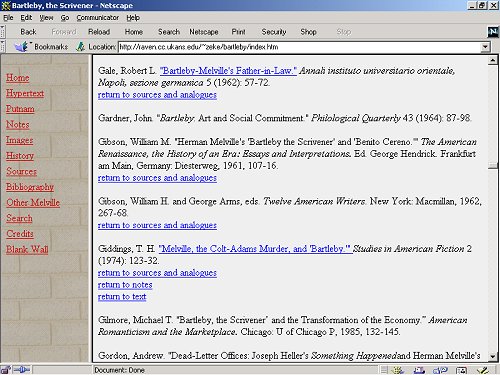

But to move on: Next is a screen from the Bibliography of Criticism list. On it are clear links to the Sources and Analogues section; but look particularly at the Gale and Giddings entries, which show the presence of the full texts of the articles, located elsewhere on this site.

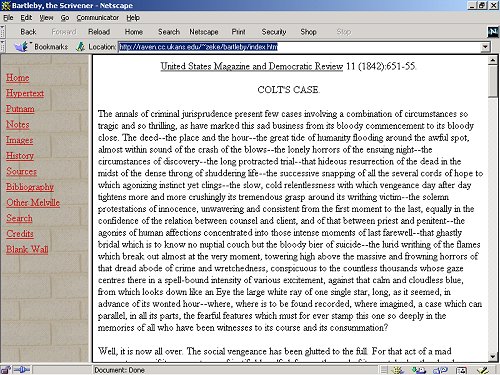

The Giddings article, concerning an historical Wall Street murder, allows you to return to the spot in the text of the story where the murder is mentioned. Another link takes you to the explanatory note about the apt Colt-Adams murder, and still another takes you to an 1842 article that may be a source for that part or more of Melville's story:

These exemplify what I mean by a layered architecture, structured for clarity and for usefulness to different sorts of users.

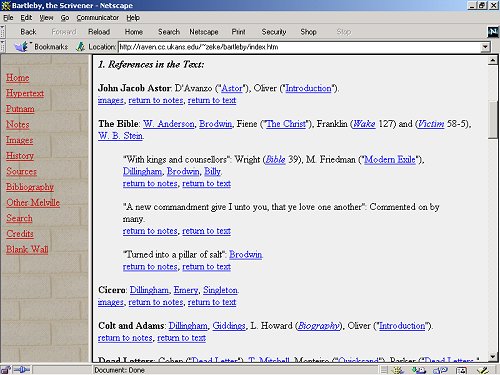

Following is a full page showing the structure and function of the section on Sources and Analogues:

Once again the navigational aids (or opportunities to exercise preference) stand out. And you can see that two articles on the important John Jacob Astor connection to "Bartleby" are available. The directly accessible note explains just who J. J. Astor was:

And the portraits of Astor as he appears in two 19th-century reference books are available to those curious enough to seek them:

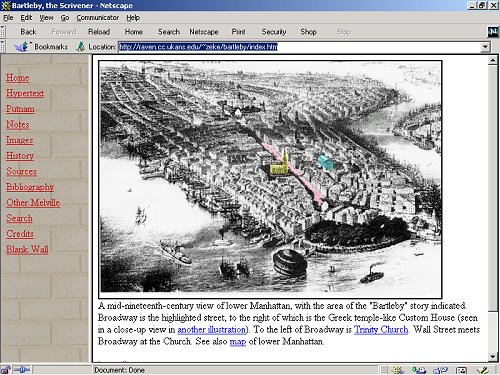

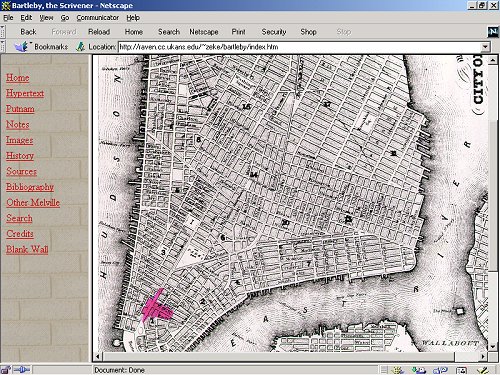

The Images section containing these Astor portraits is meant (among other things) to contribute to users' ability to visualize scenes and understand references with which Melville's contemporaries might have been familiar at first or second hand. Whether as matters of record, as expected generic components in hypermedia editing, or as pedagogical aids, they seem to me to be functionally justified. They show, for example, as the following screen captures illustrate, where the story is set:

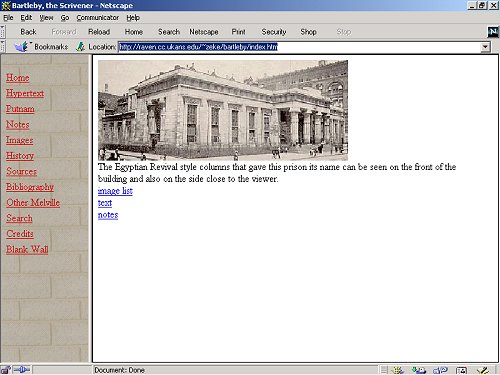

. . . why the Tombs were called that:

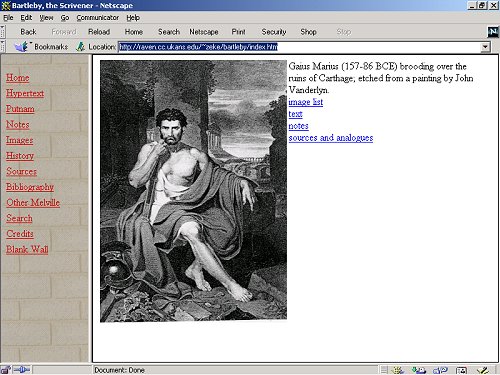

. . . what the narrator or Herman Melville might have in mind when comparing Bartleby to Marius brooding over Carthage (the image was well-known at the time):

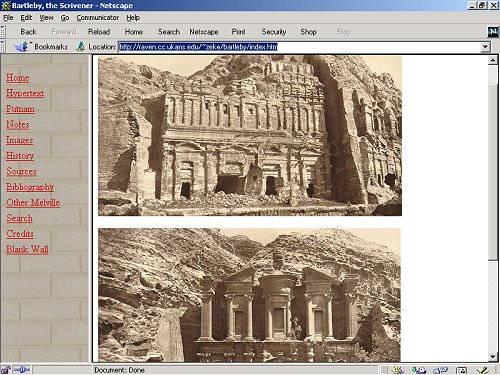

. . . and what the narrator might mean when he compares Wall Street on a Sunday to Petra, the abandoned Nabatean city in Jordan.

Once again, the links make it simple for even a neophyte to move around in the whole edition.

Finally, I shouldn't ignore the Search function:

Having the site indexed by AltaVista is of obvious utility to those beyond the University of Kansas, and actually helps with teaching it to my own students, in part because they perceive it as an international rather than just local product. Though this attitude is not shared by those who understand how a large search engine lists Web pages regardless of quality or reputation, and though all students may soon be as knowledgeable, for the moment, at least, Alta Vista gives the site a certain cachet favorable to pedagogy.

Those are probably the essentials of this hybrid site. Pedagogical implications are apparent or implicit throughout my editorial work and in the antecedent work incorporated into the edition. Here are several suggestions, though, for meaningfully using the electronic edition:

- Looking at the very few significant differences between the two texts of "Bartleby" (listed in the History of the Text), students can be led to examine the probable causes and also the effects of those revisions.

- Social censorship is one likely cause--leading to discussion of how anticipated audience responses do frequently shape texts.

- Using the list of Sources and Analogues, students can be helped to examine possibilities of "Bartleby"'s intertextuality.

- Comparing the ancillary materials and notes in the electronic edition to those in an often-used anthology of American literature, can be the basis of a good discussion on what modern readers need or want for understanding.

- Students today should be taught the differences between print and electronic textuality. This often-reprinted, often-studied story can be an excellent case study.

- Try subtlizing interpretation by using the site's images (the maps of New York City and the images of Petra may be the best examples) as interpretive resources. The proximity of Trinity Church to Wall Street, and the abandoned, commercial-looking Nabatean city ought to suggest possibilities for understanding authorial and narratorial attitudes.