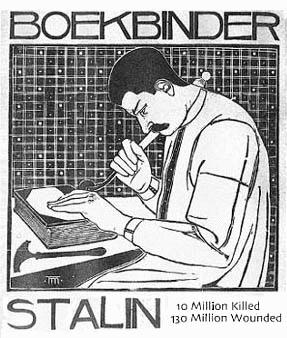

A piece I created, Boekbinder Stalin, is an example that shows the dynamics of recontextualizing. Here a juxtapositional relationship creates "an unexpected synthesis, or tension between" two previously distant ideas" (Schriver 422). This piece places Stalin in the task of binding a book. Symbolically, a bookbinder is a powerful man. In this image, he metaphorically constructs the power of the book, the power of the printed word, the teachings of humanity, the shared sense of reality. Likewise, Stalin himself wielded a enormous amount of power as leader of a mammoth nation. So, Stalin's actions, no matter what, would later be recorded in history books. We can certainly say that Stalin directed the course of history. In Boekbinder Stalin, Stalin sits in a cosmic setting, twinkling stars behind him, and binds a book; that is, he binds reality, he binds the fate of hundreds of millions of people. To this end, Stalin neurotically purged his nation of millions of people he considered threatening to the communist state. Having immigrated from the USSR, I certainly felt the presence this man tired to impose on his nation. My grandfather served in the Russian army during WWII and was even imprisoned as a POW by the Germans. After the war he returned to his family. Within two years he was again imprisoned, but in his own country. He finished his life in one of Stalin's tragic prison camps. Historians disagreed on how many millions of Russians were killed: the number my parents carry in their heads is 10 million. The small inscription of "10 million killed" on the lower right corner refers to Stalin's purging. Likewise, the phrase "130 million wounded" alludes to the relatives of those killed. Ironically, one hundred thirty million is the population of Russia in 1975, my birth year.

|

|

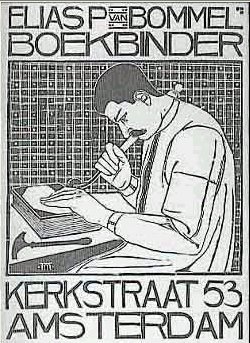

| The original illustration of a bookbinder makes no reference to Stalin. This in particular is an interesting effect of recontextualizing. The bookbinder seated is not Stalin at all. In fact, the illustration was created in 1897 and, of course, predates the 1917 revolution. My goal in Boekbinder Stalin was to make a tightly cohesive piece that had no trace of collage. In short, the trick was to keep the integrity of the original design while swapping in my own message. Aware that the original illustrator dedicated a lifetime to understanding the dynamics of his art, I took care not to corrupt his design. To keep the typography consistent, I arranged the word "Stalin" by cutting and pasting letters from the words "BOEKBINDER KERKSTRAAT AMSTERDAM," of the original piece. Likewise, even the numbering (53 and 10 Million) in both the pieces appear in the same corner. In the end, I directed my viewer to a new conclusion: that the bookbinder is Stalin. Both figures (Stalin and the bookbinder) dovetail one another and create an interesting statement. |

|

Unfortunately, creating this type of art work attracts uncourted attention to the validity of the process. Often my audience feels betrayed after I reveal that a work is a synthesis of other artists' work, as if the piece immediately loses all hope for originality and talent. I fall from the status of a creator to that of petty thief, a grave robber of certain breed. This dogma, of sorts, is too common and ill- conceived. A philosophy that restricts a visual artist to only his or her own proficiency in illustration, painting, photography, and design would likewise restrict all writers form the works in a library. In reality, we build libraries and fund education because of the obvious power of sharing, keeping, and synthesizing ideas (cut, drag, and paste). Precisely this is how the computer empowers us, for now we can stand on the shoulders of those before us with new inventiveness. For example, like the book, the computer is a presentation space where visual art can be archived and referenced; however, unlike the book, the computer is a creative space where new methods for working with knowledge are beginning to appear--recontextualizing is one such method. To communicate with recontextualized materials, an artist must engage the visible world in a different way. For example, an artist must interpret all the expectations, connotations, and allusions that occur in piece of media. An artist must understand the primary elements in a piece and be able to disassemble all of its interacting parts. It would be impractical to describe all the methodologies for visual recontextualizing, for the creative techniques are as numerous as are artists. A common thread of thought can begun from Marcel Proust's notion that: "the real voyage of discovery consists not in seeking new landscapes but in having new eyes"(Schriver 363).

|

|

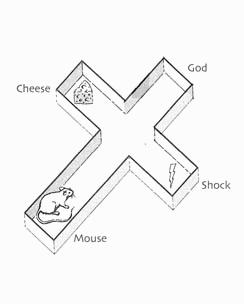

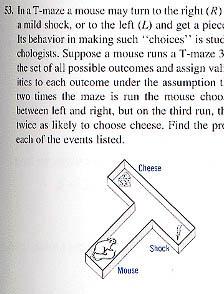

| Of Mice and Men is another piece that I created by recontextualizing. The original material came from a textbook I used for a math class. A word problem used an illustration of a Skinner Box. The first time I saw this picture I had an affinity for it because it summed up my feelings toward this math class. In particular, this mouse had a base existence; it was encouraged to perform routine and superficial tests to prove some measurable level of learning. There must be one more tunnel the mouse can chose from. Immediately when I visualized this third tunnel the illustration turned into a crucifix. What a queer turn of events. The Skinner Box, which is intended to provide insight on human behavior, takes shape as a symbol of Christianity. Once combined, something bursts out, something escapes, structures beneath structures, patterns beneath patterns. The crucifix brings with it an array of connotations and allusions. So, once the crucifix becomes a behavior modification box, new associations between the objects are produced. In other words, new meaning is created with synthesized ideas |

|

After I scanned and modified this illustration into a crucifix it still seemed rather ambiguous. That being the case, one more step was needed. As Karen A. Schriver writes in her book, The Dynamics of Document Design , "type can bind an image, directing the viewer toward a specific meaning." So I added the "stock phrase" "of mice and men" to frame the illustration into a specific idea, an antagonistic jest at Christianity.

|