Please note: The following material is the text of a presentation I delivered at CCCC in Chicago, 1998. The expanded version of this work, supported by statutory and case citation, is forthcoming in the August 1998 issue of Computers and Composition.

The Importance of Fair Use to Free Speech

Most Americans are aware that our right to free speech makes it possible, within limits, to disseminate and receive information regarding political matters, to communicate in the pursuit of truth, and to promote self-expression or self-realization; but few are aware of the fair use exemption to the copyright law, and even fewer realize its importance in relation to the goals of the first amendment. Every American citizen should understand the interrelationship between fair use and the first amendment because the policy basis on which it is built supports access to the creation of our national culture. The first amendment assures that we have a right to voice our ideas, assert conflicting views from which new thought is derived, and criticize thought and action of powerful forces in society. But fair use provides a means to access the information upon which our opinions are based. Without the fair use exception to copyright, free speech would be at best, inhibited and in some cases, eliminated altogether.

Digitization has changed the character of information to the extent that it has raised doubt regarding the clarity of the current copyright statute. The possibility of greater access and ability to copy and disseminate digitized information has induced a fearful backlash against public access, resulting in a tendency to treat information in digitized form more restrictively than its exact likeness in print (Samuelson, 1996). Corporate intellectual property lawyers who support this trend argue that reassessment and different treatment of electronically transferred material is necessary because the character of digitized information provides ease of access, copy, and dissemination. The result is that all educators, and particularly those who teach in networked classrooms could face much greater restrictions to the information that provides the basis for learning, simply because they choose the Internet as a means of access.

The backlash against public access to information, coupled with misinterpretations of the relationship between fair use and the first amendment, not only threaten our ability to access information for educational purposes, but create roadblocks for a public, which is supposedly protected in its constitutionally supported right to participate in democratic dialogue.

The words of the first amendment to the U.S. Constitution are familiar:

"Congress shall make no law . . . abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press, or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for redress of grievances" (U. S. Const. amend. I). The meaning of these words is broad and explained in various ways among legal scholars.Thomas Emerson, a leading first amendment scholar, points out that freedom of expression is based on four main premises: (1) the assurance of individual self-fulfillment and the realization of all character and potentialities of existence as a human being, (2) the existence of the essential process of advancing knowledge and discovering truth, including the assurance of the availability of information regarding all sides of an issue, (3) the provision of participation in decision-making by all members of society, and (4) the achievement of a more adaptable, hence, more stable community capable of maintaining a balance between conflict and consensus (Emerson, 1970, pp. 6-7). Joseph Hemner Jr. asserts that the writings of the founding fathers, and subsequent opinions of the courts reveal four objectives: "1) self-government, 2) search for truth, 3) social change, and 4) human dignity." He continues:

Without free and unimpaired dissemination and discussion of ideas, self-government is but a hollow fantasy. . . The link between the people and their government is maintained through debate. Free speech, then, is the tool by which democracy is maintained and improved. (Hemmer, 1979, p. 1)It is clear that the policy behind the first amendment is intended to protect the rights of all citizens to participate in individual growth, the political processes of self-government, and in the routine of influencing the developing nation.

But the right of free speech is limited by the need for balance; the majority of the Supreme Court as well as legal scholars declare that the right to free speech must be tempered by the greater needs of society (Shiffrin & Cooper, 1991, p. 2). The driving policy behind the first amendment requires the maintenance of a balance between the rights of speech in the individual and the need to establish a secure and orderly environment in which that speech might flourish. The need to support free speech does not outbalance the ultimate goal of ensuring the progress of society. "Truth is more likely to be gathered out of a multitude of tongues than through any kind of authoritative pronouncement. . . . It is for this reason that debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust, and wide open, and may well include vehement, caustic, and sometimes unpleasant attacks" (Bielefield & Cheeseman, 1997, p. 52). The law protects the speech of the individual as a means to an end of advancing society.

Copyright and Fair Use

Similarly, the constitutional grant of a limited copyright monopoly in individual creators was developed to advance these same goals of society. The constitutional provision states:

The Congress shall have power . . . to Promote the Progress of Science and the useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries. (U.S. Const. art. 1, § 8 cl. 8.)The ordering of the clauses indicates the policy intent behind the provision to ensure the advancement of societal knowledge. The means is to grant to authors a limited monopoly in their work in order to provide incentive for the development of new work. The limitation ensures the existence of a public domain. "The benefit of the copyright clause belongs ultimately to the public; the author's gain is almost incidental‹a carrot on a stick" (Hartnett, 1989, p. 271).

The fair use doctrine, a judicial creation later encoded in the statutory language of § 107 of the Copyright Act of 1976, provides specific support for the stated constitutional goals of the copyright clause. This doctrine has, since common law, supported the principal that access to information forms the basis for free speech and participatory government and that without access to information, society's ability to progress would be hindered (Patterson and Lindberg, 1991; Emerson, 1970; Gordon, 1993; Shipley, 1986). This principal specifies that fair use is an exception to the limited monopoly granted to authors in their work. The statue states:

The fair use of a copyrighted work . . . for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, . . . scholarship, or research is not an infringement of copyright. (17 U.S.C. § 107 (1982))It is significant that despite the frequent reference to the fair use defense as a privilege, it supports, instead, an exception to the limited monopoly of a copyright holder in support of a right of the public to access information, a far cry from the grant of a privilege. The right of public access is established in the policies behind both the first amendment and the copyright statute. Fair use and the first amendment are interdependent upon this point.

The relationship of the copyright clause to the First Amendment, in fact, is found in the speech protections of the copyright clause. . . For it is the common origin of the First Amendment and the copyright clause that makes clear the purpose of the constitutional policies: to protect free speech rights by preventing copyright from being used as a device of censorship, consistent with the purpose that copyright promote learning. The limitations disenable Congress from granting a copyright that would effectively give recipients of the privilege plenary control of all learning in our society. (Patterson & Birch, Jr., 1996, p. 11)Both fair use and the first amendment work to make democratic dialogue possible within a society that is dependent upon information. The Supreme Court asserted in Harper & Row, Publishers v. Nation Enterprises, that "the Framers intended copyright itself to be the engine of free expression."

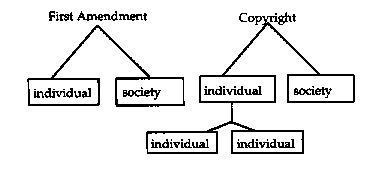

Despite the concurrent policy goals of the copyright clause in fair use and the first amendment, there are significant differences between the two legal formulations that have led to such disagreement and confusion among legal scholars that a number of analysts assert that the copyright clause and the first amendment are in conflict (Shipley, 1986; and Zimmerman, 1986 pp. 185-189). Analysis of the reasoning behind this assertion of conflict reveals a misunderstanding of the purpose of the copyright statute; to understand the flaws in the "conflict" approach also enlightens us regarding the importance of fair use to assuring a strong free speech right. The legal frameworks of the first amendment and copyright create different means of balancing public and private rights, which has led to confusion regarding their interpretation.

The basis for the assertion of conflict lies in the following reasoning: The first amendment's free speech protections ensure the free flow of information, but the copyright clause provides a limited yet exclusive statutory monopoly to authors that allows them to control access to information. A copyright can conflict with the Constitution's protections of free speech if the copyright is used to inhibit the free flow of information.

These analysts are accurate in the base of this argument, but fallaciously balance individual economic property rights treated within the copyright clause against policy rights noted in free speech. The policies of the first amendment and copyright are similar.

The first amendment balances an individual's right to free speech against the needs of society; the copyright clause, at base, balances an individual's right to control his or her work against society's need for access; however, the focus within most copyright conflicts is between one individual's economic claim in copyright against another's economic claim to use. The result is a common legal view of copyright as a grant of property to a creator against a claim to property by a user. The actual policy upon which the copyright clause is based and which supports public access, fades from discussion altogether.

To understand the commonalities in the goals of the policies behind the free speech grant and the copyright clause would lead to characterization of the copyright statute as regulatory rather than proprietory in nature, and would eliminate a claim of conflict between the copyright clause and the constitutional intent of the first amendment.

Other possible resolutions to this conflict reside in two aspects of the copyright law: 1) the law restricts access to the expression of an idea but not to the idea itself, and 2) application of fair use. But the idea/expression dichotomy fails to protect public access to information. Particularly with the ubiquity of digitized information, the access that would be allowed to ideas is limited. Digitized communication often merges the form of expression of the idea with the idea itself, so that the idea cannot be extracted from its protected form. The copyright law was developed at a time when technology had not yet advanced to a level at which it was common for ideas and expressions to become so intermingled that public access is hindered. We can no longer rely on the idea/expression dichotomy established by the copyright law to ensure the advancement of learning and knowledge creation. Fair use, then, becomes of utmost importance for protecting the public's right to information when the idea/expression dichotomy ceases to function as an assurance of protection for first amendment values.

Some legal scholars argue that a first amendment exception should be applied when the idea/ expression dichotomy fails to support the policies that ensure public access to information; but the first amendment exception is neither established law nor is it often applied by adjudicators. Fair use, then, is the only assurance of access to the information that forms the basis of free speech.

The Fair Use Doctrine remains the anchor for the policy behind the original constitutional provision, the Copyright Act, and the correspondent policy behind the first amendment. As I mentioned earlier, the fearful backlash against the speed, breadth, depth, and ease with which digital information can be accessed precipitates a tightening against fair use and public access. At the same time, access to the activities of truth-seeking and political dialogue that lead to self-government is increasing through the use of the Internet. When the public begins to rely on technology to provide the basis of information upon which to base free speech, fair use should be carefully preserved.

It is a guarantee of a free flow of information as an encouragement to learning which underlies the purpose of the Constitution's free speech clause. This constitutional guarantee of public access to information provides the common thread between the first amendment and the copyright clause. (Zimmerman, 1986, p. 168)Fair use is the precedential, and since the enactment of the 1976 Copyright Act, statutory representation of the policy of free speech and access to information that exists concurrently as the basis of the first amendment. Without the fair use exemption to copyright liability, the guarantees of the first amendment could not function.

Fair use and free expression are so interdependently entwined that it is surprising that the importance of fair use is so little acknowledged. With the advent of legislative moves to diminish the power of fair use and the tendency for courts to treat intellectual products as property, we should carefully consider the impact of a loss of fair use. Fair use is the political core of the right to teach in its grant of access to intellectual work that forms the basis for the creation of new knowledge. The life of fair use has a special relevance to those who use digitized information:

[Technology] increase[s] the amount and types of information available to the public. . . . [and] also increases the ease and speed with which information is received and disseminated. As a result the public is now accustomed to increased access to more types of information than ever before. The public expects to receive timely and complete information; therefore restricting access to this information may appear contrary to the First Amendment. (Reis, 1995, p. 289)Researchers who have become dependent upon access to ideas through digital formats require the speed and completeness with which information can be acquired to be competitive with others who have the same means of access. The more current the information is, the more valuable it is. Information with greater breadth derives deeper, more incisive commentary. Access to a great variety of sources also provides a depth of information. Electronic access makes these benefits possible in a way that print technology does not and fair use, which is applicable to digital knowledge as well as print-based information, provides a means to access information that enables the goals of free speech.

The importance of the right to free speech is clear to most Americans, but that of fair use is yet to be discovered by many. Because the value of fair use is not as well known, its existence is more vulnerable. But fair use is the lifeblood of the first amendment:

[T]here can be no complete understanding of copyright law without an understanding of its relationship to the First Amendment, arguably the single most important provision of the U. S. Constitution. In pedagogical terms, the relationship is that the copyright clause protects the right to teach . . . and the First Amendment protects the right to learn . . . in case the copyright owner wishes to deny access to the work. (Patterson & Birch, Jr., 1996)Fair use is a valuable exemption to the monopoly provided to authors in copyright. It supports the policy behind the constitutional provision that advances the creation of knowledge, which leads to self-realization and the search for truth, and makes self-government possible. Particularly in light of the threats to public access that result from the backlash of fear of the digitization of information, there is a heightened need to fight to protect the fair use exemption. The interdependent nature of fair use and free speech makes strong fair use protections necessary to a healthy first amendment. We must champion both to make the promises of democracy possible.

![]()

References

Bielefield, Arlene, & Cheeseman, Lawrence. (1997). Technology and copyright. NY: Neal-Schuman.

Emerson, Thomas. (1970). The system of freedom of expression. NY: Random.

Gordon, Wendy J. (1993). A property right in self-expression: Equality and individualism in the natural law of intellectual property. Yale Law Journal, 102, 1533-1609.

Harper & Row, Publishers v. Nation Enters., 471 U.S. 539 (1985).

Hartnett, Deborah. (1989). A new era for copyright law: Reconstituting the fair use doctrine. New York Law School Law Review, 34, 267-302.

Hemner, Jr., Joseph. (1979). Communication under law. Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow.

Patterson, L. Ray, & Birch, Jr., Stanley F. (1996). Copyright and free speech rights. Journal of Intellectual Property Law, 4, 1-23.

Patterson, L. Ray, & Lindberg, Stanley. (1991). The nature of copyright. Athens: U of Georgia P.

Reis, Leslie Ann. (1995). The Rodney King beating, beyond fair use: a broadcaster's right to air copyrighted videotape as part of a newscast." John Marshall Journal of Computer & Information Law, 13, 269-311.

Shiffrin, Steven H. & Cooper, Jesse H. (1991). The first amendment. St. Paul: West Publishing Co.

Shipley, David. (1986). Conflicts between copyright and the first amendment after Harper and Row, Publishers v. Nation Enterprises. Brigham Young University Law Review, 1986, 983-1042.

U. S. Const. amend. I.

U. S. Const. art. I § 8, cl. 8.

Zimmerman, Steven S. (1986). A regulatory theory of copyright: Avoiding a first amendment conflict. Emory Law Journal, 36, 163-211.