On the Premises

As with so many Westerns, the central idea of Lucky Luke is the need for justice.

The character of Lucky Luke was originally introduced in 1946 in a comic by Belgian creator Maurice De Bevere. Like other comics before the start of the underground comics scene, this series was intended for an audience of children.

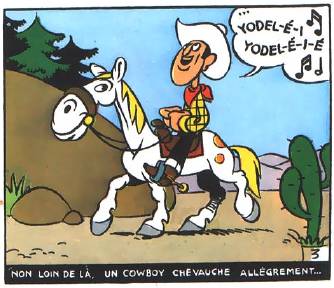

In deference to the young audience, the cartoon film Lucky Luke: Sein Größter Trick is brightly colored and chockfull of slapstick comedy and larger–than–life characters. The notion of justice is embodied in Lucky Luke himself. He is the lone cowboy righting wrongs in his own way, outside the auspices of the law.

Lest you worry the youngsters are learning the wrong things, however, have no fear.

Lucky Luke is no vigilante. Sure, he fails to turn the villainous Dalton brothers in when he encounters them after their prisonbreak. But we find out quickly that Lucky Luke has done so in order not only to protect the Daltons' intended victims, but also to rack up enough evidence against them to put them away for life.

Even when the brothers try to tempt Lucky Luke with a share of the fortune they're set to inherit, Lucky Luke's goodness does not waver. He nods and agrees to their terms, then turns to wink at Jolly Jumper, his faithful steed. It is clear to the children watching that being good is not only admirable, but also good clean fun.

Lucky Luke's justice requires no violence, not even on the part of the villains. Their violence is always foiled, and the film remains unspoiled by the presence of victims. No one is ever hurt, physically or emotionally.

This is a classic form of children's parable. No character is complex enough to warrant any exploration of emotional depth. The site of the conflict is always clearly between the very good guy and the very ill–intentioned, but ultimately bungling bad guys. This is the story of after-school specials and Disney movies. The Dalton brothers may as well be the hyenas from The Lion King or the mean girls from Mean Girls.

Within this ideology, there is no questioning of home, or choosing of cultural alliances, or developing as a person.

The only choice to be made is whether to be good or bad, and the narrative's crowning of winners and losers make that choice hardly a choice at all.