Reconstructing the Subject

Sadly, I first learned about Robert Busby after his murder in 2007. The story captured the headlines in Lansing for several months. His memorial service was held at Lansing Community College and attended by over a thousand people, and broadcast on closed circuit television (Cosentino, 2007). Between discussions in the newspapers and among those in my social circle, my interest was piqued to learn more about Mr. Busby’s life and passing. Even though I’ve lived in Lansing for most of my life, why had I never heard of Robert Busby? I felt almost embarrassed that I hadn’t known him or even known of him. My group lived in the bubble of our university and its immediate surroundings, but didn’t know much else about what was happening just down the road. Consequently, the goal for this film from the outset was to learn about the community right out our front doors.

Going into the documentary project, I knew that Robert Busby was an African-American art gallery owner who was well known for hosting blues and jazz concerts in Lansing as well as for playing the key role in creating two of Lansing’s largest yearly music festivals: JazzFest and Bluesfest.

To speak about Robert Busby, you have to also speak about Old Town Lansing. Old Town was the first established neighborhood in Lansing, the first home being built there in 1843. Originally, the neighborhood was meant to be home to the Michigan State Capitol, but instead it was built about a mile north in what is today Lansing’s downtown (Hozkiw, n.d.).

As the auto industry went into decline, Old Town Lansing suffered along with the rest of Lansing and the State of Michigan. Perhaps partially due to its location being just slightly off the beaten path, in the 60s and 70s Old Town garnered a reputation as a rough and tumble kind of place, populated with rowdy bars with imposing names like The Mustang, and serving as a haven for seedy activity such as drug use and prostitution. As one of our interviewees, Bob Blackman, said,

“Old Town wasn’t the type of place [where] you would want to walk your dog at night.”

Yet, one man saw beauty and potential in Old Town. Robert Busby, a sheet metal fabricator at the Lansing Car Assembly, would ride through Old Town every day traveling to and from work (Cosentino, 2007). While time had taken its toll on Old Town, many old buildings from the turn of the century—such as old banks, train stations, general stores, and even a tire factory—still stood, although in dilapidated condition. To be in Old Town in the early 1980s was to step into Lansing’s past, surrounded by its ornate architectural facades and characteristic exposed brick interiors.

In those old walls Busby found a canvas on which to project his dreams of a thriving Lansing art community. Because of its run-down condition, real estate in the area could be had for a song. Busby began buying up properties in the area and, being a handy kind of guy, refurbishing them. He established spaces where artwork could be displayed, no matter how avant-garde. Busby also promoted numerous jazz and blues concerts, sparking a music scene that still thrives to this day. Eventually he founded two of Lansing’s largest community festivals, BluesFest and JazzFest, which attract thousands of people to Old Town every year (Cosentino, 2007). Today, the Old Town neighborhood is recognized as one of Michigan’s greatest success stories, and has received numerous accolades, such as its distinction as an important “Main Street” as part of Michigan’s Cool Cities Initiative (Hozkiw, n.d.).

In Old Town, Busby also found a place where he felt safe to express himself. Not just a promoter of the arts but an artist himself, Busby mostly created sculptural works from found objects that told very personal stories from his past. His artwork was not the sort meant to match your couch — one piece we heard about again and again contained Busby’s own hair, and a dead rat. Often, Busby’s art expressed his frustrations with racism, tensions fostered during his experience being a young African-American growing up in a segregated town in Tennessee.

But it was the many lives that Busby touched personally that will be remembered as his life’s work. In Old Town, Bonnie Sumbler, Busby's close friend, told us, “it didn’t matter if you were the mayor or sleeping down by the railroad tracks, to Robert there was no differentiation.”

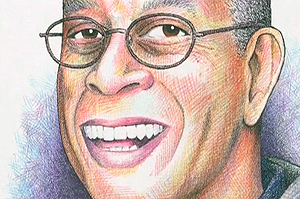

Tragically, Busby's kindness contributed to his untimely death. In 2007 he was murdered by a mentally deranged transient he had allowed to stay in his house. This man later killed himself after a brief police standoff. Busby’s murder rocked the Lansing community to its core (Cosentino, 2007). His funeral service was attended by over a thousand people, artistic works were created in his memory, and a plaque containing his likeness in Old Town was dedicated to Busby’s unofficial title as “The Mayor of Old Town.” Today, his loss is still felt deeply both by people who knew him well and those who did not. But in Old Town, his legacy lives on, and this was the legacy our group was looking to uncover.