What a Painter of "Historical Narrative" Can Show Us about War Photography |

||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||

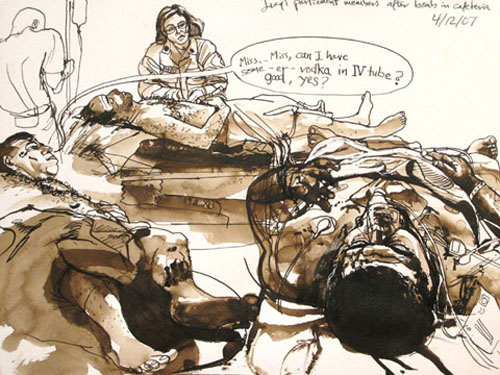

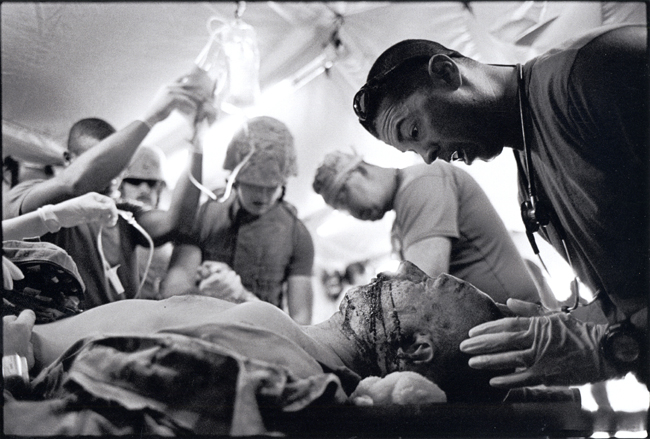

| Steve Mumford, "Mass-cas" event from a bomb in Iraqi Parliament, 2007. | James Nachtwey, Medics with a wounded marine in Iraq, 2007. |

|||||||||||

Context and Comparison: Mumford’s painting, made the same year as Nachtwey’s photo, evokes a different mood, even as it shows a patient in the foreground with blood spattered and medical personnel moving about and blending somewhat into the background. We read humor in the very non-photographic cartoon word bubble from the patient at the left: “Miss . . . Miss, can I have some—er—vodka in IV tube? good, yes?” That quip stands immediately below this text: “Iraqi parliament members after bomb in cafeteria,” a memorable juxtaposition. Beyond indicating which figure is saying it, the speech bubble takes on a graphic effect not normal in journalistic pictures. The joke hovers visually in the room, clearly part of Mumford’s experience of the scene and a part of its very composition. It reminds me of a comic book. Comparing these hospital pictures is also fascinating in how they show overlapping figures. The figures in the photo are frozen, still forms. After looking for a while at Nachtwey’s photo, I want to peek over the patient in the foreground to see what’s going on behind him, but that action is forever obscured from view. In the center of his painting, Mumford’s lines overlap. He may have drawn them by looking around the man and gurney in the foreground right, or perhaps he drew them before the man was placed there and decided to continue drawing. Either way, these overlapping lines evoke an experience of fluctuation and revision, as does the quick outline of a hunched figure working an IV tube in the background. A time-delay photo or double exposure might produce a similar effect, but such artistic modes are rarely considered appropriate as hard news. |

Theory for Analysis: To some extent, there is already a tradition in American journalism that embraces the value of art in reportage. Many of us familiar with the “new” and “gonzo” journalism of the 1960s and 1970s, as practiced by Tom Wolfe, Hunter S. Thompson, Norman Mailer, and Gay Talese, see the value in using artistic tropes to tell a news story—first person narration, playing with plot sequence, imagining the thoughts of other people on the scene, varying the spelling of words to indicate different spoken dialects, and other moves normally seen in fiction writing. Some of the best regarded Vietnam war reportage came from this school (for example, Michael Herr’s Dispatches). However, for visual images of war, hands-on art did not find its way into the mainstream consciousness surrounding Vietnam. Instead, moving pictures on the evening news took that role. Like the new journalists in the 1960s, artists depicting news events are still trying new modes, which horrify some stalwarts in the news business but nevertheless are developing a strong following. These days, comic books are seen more and more as legitimate autobiographical accounts of war and political turmoil—Art Speigelman’s In the Shadow of No Towers, Joe Sacco’s War’s End and Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis are just three examples. Scott McCloud’s (1994) seminal book on comic book theory, written and drawn as a comic book, declared, “And indeed, words and pictures have great powers to tell stories when creators fully exploit them both” (p. 152). McCloud described the exploration of the union between words and pictures as an ancient and natural mode of expression, with infinite creative possibilities. Thoughts for Class Discussion: |

| Home | Back to Top | References | by Paul X. Rutz |