RE-MEMBERING IDENTITY

|

||

| ( 4 ) | ||

“Power flows to credible messengers. Asymmetrical credibility matters. What's around information is critical.” (Defense Science Board,

“Within these interpenetrated

chronotopes, we then identify functional systems...typified and

fleeting—[that]

tie together people, artifacts, practices, institutions, communities,

and ecologies

around

some array |

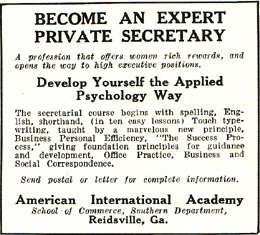

Information Networks Around 1900, as young (usually white) women from rural areas and middle-class families began to seek white-collar work in cities or larger towns, interest in ensuring their success was growing. The availability of office jobs for young women was a relatively new state of affairs, and most would-be secretaries and stenographers could not rely solely upon their mothers or grandmothers for first-hand knowledge in finding a job and navigating the workplace. As a result, many looked beyond the family to other sources of advice, which often came from existing trusted sources and institutions, like schools, teachers, counselors, women’s clubs and popular and professional periodicals. A few women's magazines—like Women's Home Companion—had begun answering work-related questions from readers well before 1910. By the 1920s, organizations like the YWCA were producing materials for the vocational instruction and moral edification of young women; meanwhile, the birth of the vocational guidance movement had educators seeking out and creating materials intended to identify, sort, and train girls and young women for professional work. This literature helped codify expectations surrounding women's presence in the office, information that was integrated into school curricula. The image on the left is from What Girls Can Do, a vocational text written by teachers at a South Philadelphia high school for girls. The first page of the text asks its reader to compare herself to Alice when she fell down the rabbit hole, warning her that

Joining educators and magazine editors in this task of “fitting” readers for work were writers with experience in career counseling and personnel management, as well as freelance journalists and other professional women. Although career counseling and personnel management were new professions, they placed women in established institutions—schools, workplaces, government offices—where their ideas could shape policies and curricula, in turn affecting many more women (and men) than might ever have chosen to read a particular career advice text. The advice writers themselves tended to be well-educated, middle- and upper-class women who were clustered in urban centers—particularly the East Coast and Chicago—so it was the use of existing social, commercial, and institutional channels that helped move their messages to the masses. Their texts were read by other authors, personnel managers, teachers, counselors, and leaders of women’s clubs who helped spread the gospel of workplace etiquette and deportment. Taken together, these texts created a remarkably effective information network, one supplemented by talks given to women’s clubs and interviews broadcast over the radio. This network thus capitalized on existing social, institutional, and media channels to circulate and cement the common (if sometimes contradictory) wisdom growing up around office work in the 1920s, ‘30s, and ‘40s. |

|