My Experience with Assembling

I have long been infatuated with this notion of assemblage as a community building

activity; for 25 years, I have been creating print assemblings in

a variety of classes. Students have created magazines in first-year writing

classes; a collection of found poetry in a literature class; multimodal explorations

of words and images in visible rhetoric classes; collections of personal essays

about reading in introduction-to-the-English-major courses; collections of

PageMaker documentation for technical writing classes; and most recently in

a technical writing pedagogy class focusing on narrative, I had students create

a page that told a story based on their final project. And the assemblings

have all been a success. The work may have been uneven over the years, but

the excitement and the sense of community have been constant. I am convinced

that it is the act of performance that builds this community: The experience

of being responsible for text, design, and printing, and then sharing what

you have created brings a class together like nothing else (for more about

the history of classroom publishing, see Chapter 9 of The Computer and

the Page).

This interest in assembling class anthologies dates back to my undergraduate days at Michigan State University when I participated in a small press assembling in 1971 (a year after the first issues of Assembling magazine had been published). One of my creative writing teachers, Albert Drake, was a truly remarkable multimodal teacher working a full decade before the personal computer. He had been producing a small press magazine, Happiness Holding Tank, on 8-1/2 by 11 mimeo pages lovingly hand-pulled from the English department's mimeo machine. On the verge of burning out, he decided to give Kostelantz's notion of assembling a try and sent out invitations to writers, artists, and students in the East Lansing area.

I was excited by the invitation, but also utterly stumped. As the day of the assembling neared, I had nothing.

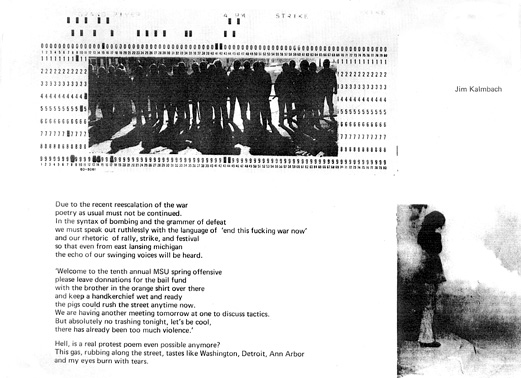

It was the height of protest against the war in Viet Nam, passions had been spiked by the bombing of Cambodia, and the day before we poets were to gather, the campus was blanketed with computer punch cards (3 x 8-inch beige cards on which we punched information to be fed into mainframe computers, really). At the top of the cards was printed "Grand River 4 PM Strike." Grand River was the main drag that separated the campus from the town. I went and chanted slogans such as, "Hell no, we won't go." Although nothing much else happened (this was East Lansing, not Ann Arbor, Madison, or Berkeley), the image of the local police standing shoulder to shoulder across Grand River Avenue dressed in riot gear and billy clubs while the bittersweet smell of tear gas curled along the sidewalk is my most vivid memory of the anti-war movement.

The next day, the day we were to assemble the magazine, a picture appeared in the local paper of the police standing across Grand River Avenue along with another picture of some woman being tear-gassed. I grabbed a punch card, cut out the pictures, wrote a quick anti-war poem, typed it up on the Art Department's Compositor (an IBM typewriter on steroids), and rubber-cemented everything together. And about two hours before we were to gather, I went to a local printer who said, sorry, I can't print something that uses the F-word. My luck to find a printer who actually read what he printed. I raced to another quickie offset shop (Xerox machines were rare then and very poor quality) with a mournful tale of procrastination, inspiration, censorship, and a look of sheer desperation that got my poem printed. Instant publishing circa 1971.

The party at which we assembled the magazine was itself a happening: One art student constructed a large plastic inflatable dome (which the children loved), while an American Studies major showed 16 mm Speedy Alka-Seltzer commercials (his page was a homage to Speedy, complete with a two-inch slice of film from a real commercial stapled to the page). I particularly remember the long line of glittering pages snaking through Drake's house. We took turns collating copies that he would staple together and bind with red tape. At the end of the night, we each got to take home fifteen copies to sell or give away.

Two years later, Drake (1973) wrote an article about the life and death of small press magazines, and his own frustrations with producing Happiness Holding Tank. What he had to say about the assembling issue is particularly notable in terms of our experiences today teaching digital, multimodal composition:

Essentially each contributor was faced with a question: what to do with a sheet of 8 1/2" X 11" paper? They answered it in really imaginative ways; no editor could plan a mag like this, and he could never get this kind of work if he waited for it to come through the mail . . . As a learning process the magazine was much more successful than any class I've had. I watched some of the contributors work to get something on that sheet, and had seen their ideas shift, change, grow; good ideas were tossed out, developed into better ones. People who were somewhat stumped for what they considered a suitable idea in the beginning ended up with more ideas than they could carry out. . . The people in HHT 6 were, for the most part, strangers to each other even though they lived in the same community; the magazine brought them together, and it's nice to be able to be in the same room with the writer whose work you're reading, and to know your work is being read by that person as well (np).

Here is a very poor scan of my first venture into assembling, "Grand River 4 PM Strike." Happiness Holding Tank 6 (1971): np.