Most

instructors would not consider themselves analysts or their students analysands—and

just as many would not even want to. Yet the cathartic nature of the

student-centered composition class makes us so,  whether

we like it or not. But this is a good thing. A leveled dialectic

typically transpires in Composition 101, and students eventually enact their

own "alienation, anxiety, shame, desire, symptom" (Bracher 123) through

writing and discussions. We frequently transcend the institutionalism

found in other departments, in other disciplines when we take on the discourse

of the Analyst and ask students to reconsider their sense of self and the

source of their ideas; most instructors in other disciplines perpetuate

that of the Master. The discourse of the Analyst enables the analysand/student

to communicate that which has been beyond symbolization—the manufactured,

unspeakable desires of the Other. Lacan's genius, whether

we like it or not. But this is a good thing. A leveled dialectic

typically transpires in Composition 101, and students eventually enact their

own "alienation, anxiety, shame, desire, symptom" (Bracher 123) through

writing and discussions. We frequently transcend the institutionalism

found in other departments, in other disciplines when we take on the discourse

of the Analyst and ask students to reconsider their sense of self and the

source of their ideas; most instructors in other disciplines perpetuate

that of the Master. The discourse of the Analyst enables the analysand/student

to communicate that which has been beyond symbolization—the manufactured,

unspeakable desires of the Other. Lacan's genius,  of

course, is that he bridges psychoanalysis and Marxism, and we discover that

the veiled origins of these desires are the culture industry as well as

the nuclear family. If Giroux is correct and "[c]ritical pedagogy needs

to develop a theory of educators and cultural workers as transformative

intellectuals who occupy specific political and social locations" (Border

78), then such theorizing will certainly benefit from the reflexivity drawn

from an analysis of the posthuman condition—accomplished simply through

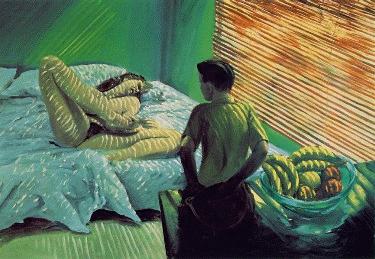

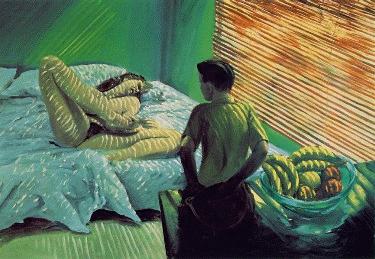

peer review of a hypertext essay. Richard Benjamin, our Westworld

vacationer, might have benefited, too, had he chosen cybernetics instead

of androids, his first gamble. of

course, is that he bridges psychoanalysis and Marxism, and we discover that

the veiled origins of these desires are the culture industry as well as

the nuclear family. If Giroux is correct and "[c]ritical pedagogy needs

to develop a theory of educators and cultural workers as transformative

intellectuals who occupy specific political and social locations" (Border

78), then such theorizing will certainly benefit from the reflexivity drawn

from an analysis of the posthuman condition—accomplished simply through

peer review of a hypertext essay. Richard Benjamin, our Westworld

vacationer, might have benefited, too, had he chosen cybernetics instead

of androids, his first gamble. |

whether

we like it or not. But this is a good thing. A leveled dialectic

typically transpires in Composition 101, and students eventually enact their

own "alienation, anxiety, shame, desire, symptom" (Bracher 123) through

writing and discussions. We frequently transcend the institutionalism

found in other departments, in other disciplines when we take on the discourse

of the Analyst and ask students to reconsider their sense of self and the

source of their ideas; most instructors in other disciplines perpetuate

that of the Master. The discourse of the Analyst enables the analysand/student

to communicate that which has been beyond symbolization—the manufactured,

unspeakable desires of the Other. Lacan's genius,

whether

we like it or not. But this is a good thing. A leveled dialectic

typically transpires in Composition 101, and students eventually enact their

own "alienation, anxiety, shame, desire, symptom" (Bracher 123) through

writing and discussions. We frequently transcend the institutionalism

found in other departments, in other disciplines when we take on the discourse

of the Analyst and ask students to reconsider their sense of self and the

source of their ideas; most instructors in other disciplines perpetuate

that of the Master. The discourse of the Analyst enables the analysand/student

to communicate that which has been beyond symbolization—the manufactured,

unspeakable desires of the Other. Lacan's genius,  of

course, is that he bridges psychoanalysis and Marxism, and we discover that

the veiled origins of these desires are the culture industry as well as

the nuclear family. If Giroux is correct and "[c]ritical pedagogy needs

to develop a theory of educators and cultural workers as transformative

intellectuals who occupy specific political and social locations" (Border

78), then such theorizing will certainly benefit from the reflexivity drawn

from an analysis of the posthuman condition—accomplished simply through

peer review of a hypertext essay. Richard Benjamin, our Westworld

vacationer, might have benefited, too, had he chosen cybernetics instead

of androids, his first gamble.

of

course, is that he bridges psychoanalysis and Marxism, and we discover that

the veiled origins of these desires are the culture industry as well as

the nuclear family. If Giroux is correct and "[c]ritical pedagogy needs

to develop a theory of educators and cultural workers as transformative

intellectuals who occupy specific political and social locations" (Border

78), then such theorizing will certainly benefit from the reflexivity drawn

from an analysis of the posthuman condition—accomplished simply through

peer review of a hypertext essay. Richard Benjamin, our Westworld

vacationer, might have benefited, too, had he chosen cybernetics instead

of androids, his first gamble.