Conclusion

Imagining different futures for captioning

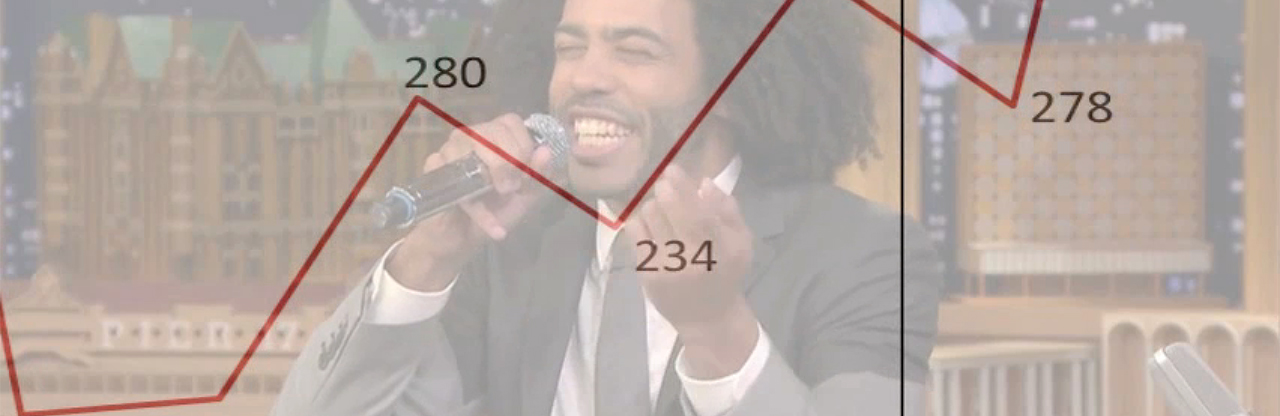

Reading speed guidelines are typically reduced to numbers without explanation. For example, 160 words per minute [wpm] is one recommended limit for upper-level educational media (Described and Captioned Media Program, "Presentation Rate," 2017). But what does 160 wpm feel like? How does it scan in real time across multiple captions of varying speeds? Daveed Diggs' rapping prowess in Hamilton is well-known (in one song, he sings nineteen words in three seconds, which is 380 wpm). In this frame from his 2016 appearance on The Tonight Show, Diggs demonstrates his rapping speed with a verse from a song from his group, Clipping. I calculated the speed of each line and then created a line graph, which I superimposed and animated over the clip. To be clear: I do not offer this experiment as a viable alternative to traditional captions but rather as a way for us to better understand reading speed, by embodying it as more than an abstract number or command.

Reading speed guidelines are typically reduced to numbers without explanation. For example, 160 words per minute [wpm] is one recommended limit for upper-level educational media (Described and Captioned Media Program, "Presentation Rate," 2017). But what does 160 wpm feel like? How does it scan in real time across multiple captions of varying speeds? Daveed Diggs' rapping prowess in Hamilton is well-known (in one song, he sings nineteen words in three seconds, which is 380 wpm). In this frame from his 2016 appearance on The Tonight Show, Diggs demonstrates his rapping speed with a verse from a song from his group, Clipping. I calculated the speed of each line and then created a line graph, which I superimposed and animated over the clip. To be clear: I do not offer this experiment as a viable alternative to traditional captions but rather as a way for us to better understand reading speed, by embodying it as more than an abstract number or command.

Enhanced captions are admittedly idealistic. They don't account for the expertise, time, money, and user studies that are required to make them viable. They ignore the institutional power structures that separate captioners from producers and reduce the costs of captioning to a tiny fraction of a film budget. They disrespect traditional boundaries and, in some cases, fundamentally alter the meanings of programs. They raise ethical questions. They assume that captioning must involve high-end graphic design (or that producers should be captioners or vice versa). They assume that captioning is highly creative and situated. They transform text and type into an image by burning the text onto the screen, which is the "antithesis" of an accessible enhancement (Hall, 2017). They slow down the practice of captioning at a time when so much content, especially online, demands to be captioned quickly, efficiently, and semi-automatically (Loftus, 2017). Enhanced captions also compromise users' reading speed, because kinetic typography "decelerate[s] the communication process" (Hillner, 2005, p. 167).

None of these criticisms can rescue the status quo, however. Current captioning technology and style guidelines leave much to be desired: "upper-case white text on black background...is still the most common format recommended by the captioning standards and used for television captioning" (Udo & Fels, 2010, p. 208). Even if we remain highly skeptical of experimental forms, we should still be alarmed at the lack of innovation in captioning style and technology compared with the enormous changes in the entertainment and computer technology sectors over the same period.

It is time to imagine different futures for captioning, futures that welcome experimentation and multiple approaches, question the hegemony of the word, and elevate the needs of viewers who are deaf and hard of hearing. It is time to make room for captions. Instead of assuming that captions can only be squeezed into a small space at the bottom of an already-designed film space, space itself might be designed for and with captioning. Janine Butler (2017) has explored how the concept of "DeafSpace"—made popular in Gallaudet University's philosophy of designing the built environment specifically for students and faculty who communicate in sign language—can reshape approaches to film design. For example, shots can be framed to take into account, and make room for, the placement of captions to aid readability, allowing captions and characters (e.g., lip movements) to bind together more tightly. My experimental placement of ghostly captions on either side of Lili Taylor in The Haunting was a happy accident, not the result of a production-level decision to make room for captions. In fact, all of my preceding experiments began with an already designed space that wasn't built for accessibility. In caption studies, we need to imagine film space differently. I am inspired by—and aim to position caption studies in response to—Alison Kafer's (2013) call to "imagin[e] futures and futurity otherwise" for people with disabilities (p. 27).

Enhanced captions do not have to replace other viable options, including high quality autocaptioning, but could become one option among many, particularly on films with large budgets. Enhanced captions could intermingle freely with traditional captions, following the lead, perhaps, of a film like Night Watch in which a small number of experimental subtitles playfully disrupt the flow of traditional subtitles. Enhanced captions could also offer greater flexibility to users beyond the typeface, type size, and color options that our digital televisions and web interfaces allow. I offer the preceding experiments in the spirit of a critical rhetoric that values "never-ending skepticism, hence permanent criticism" (McKerrow, 1989, p. 96). Experimenting with new forms of captioning is an act of "re-creation" (p. 102), and one way, perhaps, to push back against taken for granted norms and conventions.

The composition and technical communication classrooms are already spaces for experimentation when students are engaged with multiple modes to create meaning for specific purposes and audiences. They routinely work with on-screen text in their video projects, from titles to end credit sequences. Accessibility can be folded into these discussions in the name of universal design. Instead of ending a video assignment with captioning, instructors can be challenged to begin with captioning, or at least to keep it in mind throughout the life of a project. When students design for captions, they consider how film space and caption space can co-exist and complement each other. They design for situations in which meaning needs to be conveyed with the sound turned off, and they design for audiences who depend on quality captions. They don't reduce audio accessibility to transcription but recognize that creativity and skill are involved in leveraging the resources of language and other signs to solve hard problems. To design captions is to remove the barrier that has limited captioning to words on the bottom-center of the screen.

This webtext is an invitation to composition and technical communication instructors to fold captioning into the creative process, to center the needs of viewers who are deaf or hard of hearing, to design for more diverse audiences by questioning the entrenched notion of the default hearing user, and to consider how our understanding of audio accessibility might be expanded to include non-linguistic signs.

Extremely rapid speech throws into relief the limits of traditional captions. Source: The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon. Featured guest Daveed Diggs. May 9, 2016. Captioned by the author. Animated line graph displays the reading speed (in words per minute) of each caption in real time. The line graph was created by the author in Microsoft Excel and Adobe After Effects. The goal wasn't to provide alternative captions but to animate reading speed as more than a number.

Source: Three Musketeers, 2011. DVD. Custom captions were created by the author in Adobe After Effects to mimic the experience of being drugged. This clip was the first example I tried to animate. It inspired the other examples in this webtext.

References

Aitken, Jonathan. (2006). Haiku in motion: Kinetic typography enhances poetic meaning. International Journal of the Humanities, 3(5), 57–62.

Armisen, Fred, Brownstein, Carrie, Krisel, Jonathan, & Oakley, Bill (Writers), & Krisel, Jonathan (Director). (December 14, 2012). Winter in portlandia [Television series episode]. In Lorne Michaels, Jonathan Krisel, Fred Armisen, Carrie Brownstein, & Andrew Singer (Executive Producers), Portlandia. New York, NY: Broadway Video.

Blum, Jason, & Clark, Sherryl (Producers), & Joost, Henry, & Schulman, Ariel (Directors). (2016). Viral [Motion picture]. United States: Dimension Films.

Bond, Lily. (2018, January 4). Roll-up vs. pop-on captions: What's the difference? 3Play Media. Retrieved April 15, 2018, from https://www.3playmedia.com/2014/09/26/roll-up-vs-pop-on-captions-whats-difference/

Brady, & Rasheed Newson (Producers), The 100. New York, NY: Alloy Entertainment.

British Broadcasting Corporation [BBC]. (2017). Subtitle guidelines. Retrieved November 7, 2017, from http://bbc.github.io/subtitle-guidelines/

Brownie, Barbara. (2015). Transforming type: New directions in kinetic typography. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Brumberger, Eva R. (2003). The rhetoric of typography: The persona of typeface and text. Technical Communication 50(2), 206–

Butler, Janine. (2017). Creating a (deaf)space for the fluidity of captions in video compositions. Paper presented at: Conference on College Composition and Communication. Portland, OR: NCTE.

Ceraso, Steph. (2014). (Re)Educating the senses: Multimodal listening, bodily learning, and the composition of sonic experiences. College English, 77(2), 102-123.

Craft, Elizabeth, & Fain, Sarah (Writers), & White, Dean (Director). (April 2, 2014). Earth kills [Television series episode]. In Jae Marchant, Tim Scanlan, Aaron Ginsburg, Wade McIntyre, T.J. Brady, & Rasheed Newson (Producers), The 100. New York, NY: Alloy Entertainment.

Deeley, Michael (Producer), & Scott, Ridley (Director). (1982). Blade Runner [Motion picture]. United States: Warner Bros.

Described and Captioned Media Program. (2017). Presentation Rate. Retrieved November 7, 2017, from http://www.captioningkey.org/presentation_rate.html

Described and Captioned Media Program. (2017). Speaker identification. Retrieved November 7, 2017, from http://www.captioningkey.org/speaker_identification.html

Described and Captioned Media Program. (2017). Text. Retrieved November 7, 2017, from http://www.captioningkey.org/text.html

DeVito, Danny, Shamberg, Michael, Sher, Stacey, & Lyon, Gail (Producers), & Niccol, Andrew (Director). (1997). Gattaca [Motion picture]. United States: Columbia Pictures.

Donner, Lauren Shuler, Melniker, Benjamin, Uslan, Michael E., Stoff, Erwin, di Bonaventura, Lorenzo, & Goldsman, Akiva (Producers), & Lawrence, Francis (Director). (2005). Constantine [Motion picture]. United States: Warner Bros. Pictures.

Donner, Richard, & Bernhard, Harvey (Producers), & Donner, Richard (Director). (1985). The Goonies [Motion picture]. United States: Warner Bros.

Doyle, Tim (Writer), & Wass, Ted (Director). (February 28, 2014). Stud muffin [Television series episode]. In John Amodeo (Producer), Last man standing. Los Angeles, CA: 20th Television.

Ernst, Konstantin, & Maksimov, Anatoli (Producers), & Bekmambetov, Timur (Director). (2004). Night watch [Motion picture]. Russia: Gemini Films.

Federal Communications Commission [FCC]. (2000 July 21). Summary of FCC order on closed captioning requirements for digital television receivers. Retrieved November 7, 2017, from http://transition.fcc.gov/Bureaus/Mass_Media/News_Releases/2000/nrmm0031.html

Hall, Charles. (2017, November 14). Open captioning [Blog post]. Retrieved April 13, 2018, from https://medium.com/@hall_media/open-captioning-d4e4e93647d

Hillner, Matthias. (2005). Text in (e)motion. Visual Communication, 4(2), 165–71.

Hodge, Chad (Writer), & Shyamalan, M. Night (Director). (May 14, 2015). Where paradise is home [Television series episode]. In Ron French & Shawn Williamson (Producers), Wayward pines. Los Angeles, CA: 20 th Television.

Hong, Richang, Wang, Meng, Xu, Mengdi, Yan, Shuicheng, & Chua, Tat-Seng. (2010). Dynamic captioning: Video accessibility enhancement for hearing impairment. In Proceedings of ACM Multimedia Conference (pp. 421–30). Firenze, Italy: ACM.

Iwanyk, Basil, Leitch, David, Longoria, Eva, Witherill, Michael (Producers), & Stahelski, Chad (Director). (2014). John Wick [Motion picture]. United States: Summit Entertainment.

Jensema, Carl. (1998). Viewer reaction to different television captioning speeds. American Annals of the Deaf 143(4), 318–24.

Jensema, Carl J., Danturthi, Ramalinga Sarma, & Burch, Robert. (2000). Time spent viewing captions on television programs. American Annals of the Deaf, 145(5), 464–68.

Jones, Natasha N., Moore, Kristen R., & Walton, Rebecca. (2016). Disrupting the past to disrupt the future: An antenarrative of technical communication. Technical Communication Quarterly, 25(4), 211–29.

Kafer, Alison. (2013). Feminist, queer, crip. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

197 [Television series episode]. In Stephen Colbert, Jon Stewart, Chris Licht, Tom Purcell, & Barry Julien (Executive Producers), The late show with Stephen Colbert. Los Angeles, CA: CBS Television Studios.

Kauffman, Tom (Writer), & Myers, Jeff (Director). (January 13, 2014). M. Night Shaym-Aliens! [Television series episode]. In J. Michael Mendel & Kenny Micka (Producers), Rick and Morty. Atlanta, GA: Cartoon Network.

Kennedy, Kathleen, Abrams, J. J., & Burk, Bryan (Producers), & Abrama, J. J. (Director). (2015). Star wars: The force awakens [Motion picture]. United States: Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures.

Kring, Tim (Writer), & Lawrence, Francis (Director). (January 25, 2012). Pilot [Television series episode]. In Dennis Hammer, Brynn Malone, & Robert Levine (Producers), Touch. Los Angeles, CA: 20 th Television.

Lacy, Lyn Ellen. (1986). Art and design in children's picture books: An analysis of Caldecott award-winning illustrations. Chicago, IL: American Library Association.

Lee, Johnny C., Forlizzi, Jodi, & Hudson, Scott E. (2002). The kinetic typography engine: An extensible system for animating expressive text. In User Interface Software & Technology Symposium, 4(2), 81–90.

Lee, Joonhwan, Jun, Soojin, Forlizzi, Jodi, & Hudson, Scott E. (2006). Using kinetic typography to convey emotion in text-based interpersonal communication. In Proceedings of the 6th Conference on Designing Interactive Systems (pp. 41–49). University Park, PA: ACM.

Lewis, Victoria Ann. (2015). Crip. In Rachel Adams, Benjamin Reiss, & David Serlin (Eds.), Keywords for disability studies (pp. 46–7). New York: New York University Press.

Loftus, Patrick. (2017, August 25). Auto-captions vs. editing auto-captions vs. re-captioning in post-production. 3Play Media. Retrieved November 11, 2017, from http://www.3playmedia.com/2017/08/25/recaptioning-vs-editing-live-captions-and-autocaptions/

Malik, Sabrina, Aitken, Jonathan, & Waalen, Judith Kelly. (2009). Communicating emotion with animated text. Visual Communication, 8(4), 469–79.

McKerrow, Raymie. (1989). Critical rhetoric: Theory and praxis. Communication Monographs, 56, 91–111.

McKee, Heidi. (2006). Sound matters: Notes toward the analysis and design of sound in multimodal webtexts. Computers & Composition 23, 335&54.

McRuer, Robert. (2006). Crip theory: Cultural signs of queerness and disability. New York: New York University Press.

Mrksa, Kris (Writer), & Freeman, Emma (Director). (July 16, 2015). Am I in hell? [Television series episode]. In Ewan Burnett & Louise Fox (Producers), Glitch. Sydney, Australia: Matchbox Pictures.

National Association of the Deaf (n.d.) Television and closed captioning. Retrieved October 10, 2017, from https://www.nad.org/resources/technology/television-and-closed-captioning/

Parker, Trey (Writer), & Parker, Trey (Director). (November 18, 2015). Sponsored content [Television series episode]. In Vernon Chatman (Producer), South Park. New York, NY: Viacom Media Networks.

Portland, Oregon. (2015). Require activation of closed captioning on televisions in public areas. Ordinance No. 187454. Code Section 23.01.075. Retrieved October 22, 2017, from https://www.portlandoregon.gov/article/556056

Phillips, Julia, & Phillips, Michael (Producers), & Spielberg, Steven (Director). (1977). Close encounters of the third kind [Motion picture]. United States: Columbia Pictures.

Rashid, Raisa, Aitken, Jonathan, & Fels, Deborah I. (2006). Expressing emotions using animated text captions. In Klaus Miesenberger, Joachim Klaus, Wolfgang Zagler, & Arthur Karshmer (Eds.), Proceedings from: Computers Helping People With Special Needs: 10th International Conference (pp. 24–31). Linz, Austria: Springer.

Rashid, Raisa, Vy, Quoc, Hunt, Richard, & Fels, Deborah I. (2008). Dancing with words: Using animated text for captioning. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 24(5), 505–519.

Rawsthorn, Alice. (2007, May 27). The director Timur Bekmambetov turns film subtitling into an art. The New York Times. Retrieved November 7, 2017, from http://www.nytimes.com/2007/05/25/style/25iht-design28.1.5866427.html

Roller, Matt (Writer), & Archer, Wes (Director). (July 26, 2015). A rickle in time [Television series episode]. In J. Michael Mendel & Kenny Micka (Producers), Rick and Morty. Atlanta, GA: Cartoon Network.

Rosenberg, Grant. (2007, May 15). Rethinking the art of subtitles. Time. Retrieved November 7, 2017, from http://content.time.com/time/arts/article/0,8599,1621155,00.html

Roth, Donna, Wilson, Colin, & Arnold, Susan (Producers), & Bont, Jan de (Director). (1999). The Haunting [Motion picture]. United States: DreamWorks Pictures.

Sandahl, Carrie. (2003). Queering the crip or cripping the queer? Intersections of queer and crip identities in solo autobiographical performance. GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, 9(1-2), 25–56.

Schafer, R. Murray. (1977). The soundscape: Our sonic environment and the tuning of the world. Rochester, NY: Destiny Books.

Strapparava, Carlo, Valitutti, Alessandro, & Stock, Oliviero. (2007). Dances with words. In Proceedings from: 20th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (pp. 1719–1724). Menlo Park, CA: ACM.

Udo, John-Patrick & Deborah I. Fels. (2010). The rogue poster-children of universal design: Closed captioning and audio description. Journal of Engineering Design, 21(2-3), 207–221.

Vy, Quoc V. (2012). Enhanced captioning: Speaker identification using graphical and text-based identifiers (Master's thesis). Retrieved from Ryerson University. (Paper 1702). Retrieved June 6, 2016, from http://digital.library.ryerson.ca/islandora/object/RULA:1956

Vy, Quoc V., & Fels, Deborah I. (2009). Using avatars for improving speaker identification in captioning. In Tom Gross et al. (Eds.), INTERACT 2009, Part II, LNCS 572 (pp. 916–19). Berlin: International Federation for Information Processing.

Vy, Quoc V., Mori, Jorge A., Fourney, David W., & Fels, Deborah I. (2008). EnACT: A software tool for creating animated text captions. In Klaus Miesenberger, Joachim Klaus, Wolfgang Zagler, & Arthur Karshmer (Eds.), Proceedings from: Computers Helping People With Special Needs: 11th International Conference (pp. 609–616). Linz, Austria: Springer.

Yergeau, M. Remi, Brewer, Elizabeth, Kerschbaum, Stephanie, Oswal, Sushil K., Price, Margaret, Selfe, Cynthia L., Salvo, Michael J., & Howe, Franny. (2013). Multimodality in motion: Disability and kairotic spaces. Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy, 18(1). Retrieved November 11, 2017, from http://kairos.technorhetoric.net/18.1/coverweb/yergeau-et-al/pages/access.html

Zdenek, Sean. (2015). Reading sounds: Closed-captioned media and popular culture. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.