[ Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1907) with illustrations by Arthur Rackham ]

II. The Pool of Tears

As Alice shrinks from giant to tiny, she contemplates her own identity—an identity that is only partially complete in the unillustrated text. The continual re-illustration of Alice is particularly transformative because the images play a role not unlike that Perry Nodelman identified as distinctive to illustrations in piture books:

Rather than invite viewers to make imaginative guesses about the story it implies, a picture in a picture book confirms and makes more specific a story that is already implied by the context of previous and subsequent pictures and also at least partially told in an accompanying text. (viii)

This relationship parallels the engagement of visual and text in comics—appropriately, given original illustrator Tenniel was a comics artist. In such works, as Thomas E. Wartenberg notes of Tenniel's Alice, "our imaginings... are determined by the illustrations" (25).

Dear, dear! How queer everything is to-day! And yesterday things went on just as usual. I wonder if I've been changed in the night? Let me think: was I the same when I got up this morning? I almost think I can remember feeling a little different. But if I'm not the same, the next question is, Who in the world am I? Ah, that's the great puzzle!

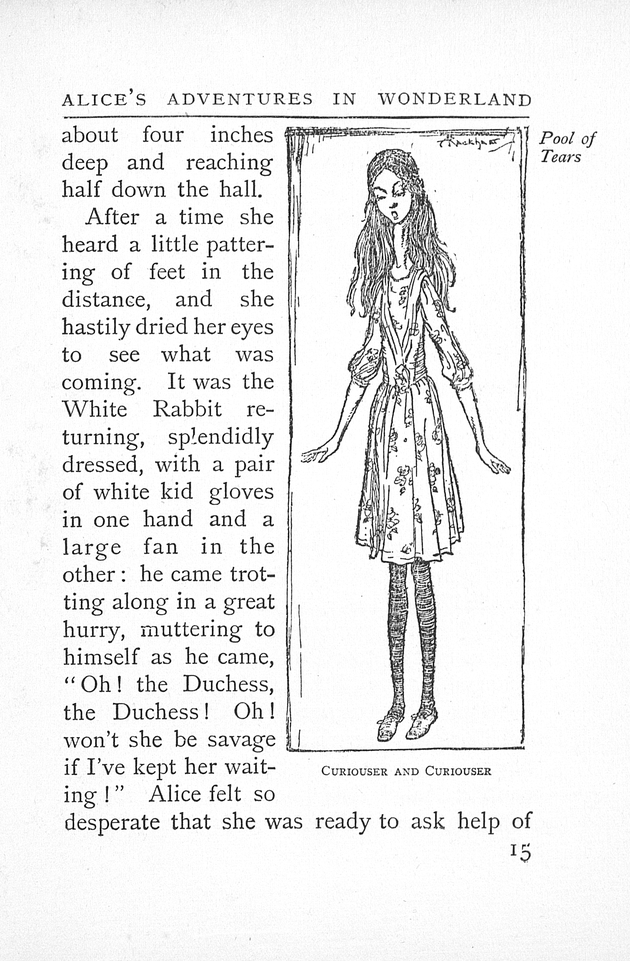

Encountering the Alice text with different illustrations can thus build a very different image of both girl and Wonderland. Alice's own question, "Who in the world am I?", is perhaps impossible to answer. Will Brooker critiqued the engagement of Arthur Rackham's Alice, who

seems distressed by her sudden growth in the early scene, by the flying plates in the Duchess' house, and by the rising up of the pack of cards, but her face when surrounded by huge animals and swimming the pool of her own tears is telling—she looks bored. (123)

Unlike the visibly weeping Alice of Mabel Lucie Attwell or the composed if slightly startled Alice of John Tenniel, Rackham's Alice seems apart from her own story. The art occupies the same space on the page, but fills it differently, and it is juxtaposed with a different stage of the text. These structural differences make each print adaptation a different textual experience—as removed from Tenniel's version as from the original manuscript—with a different Alice living within its pages.